In the opening pages of The Lasting Harm, journalist Lucia Osborne-Crowley travels to West Palm Beach to meet “Carolyn”, a victim-survivor of Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking network. Her testimony supported the most serious charges in the prosecution’s case against the co-conspirator Epstein described as his “best friend”: his former girlfriend Ghislaine Maxwell.

“Carolyn” has never spoken to a journalist at length and is anxious to know why Osborne-Crowley wants to write the story.

I answer honestly, “I was sexually abused and groomed as a child […] And I’m still living with the effects of it. I want the world to understand it better.”

Osborne-Crowley is a survivor of sexual abuse, perpetrated against her by her gymnastics coach from the age of nine. She was later violently raped by a stranger in a Sydney public toilet, aged 15, compounding her trauma. She first disclosed it ten years later, aged 25.

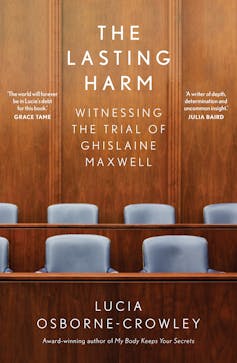

Review: The Lasting Harm: Witnessing the trial of Ghislaine Maxwell – Lucia Osborne-Crowley (Allen & Unwin)

She has written two books about her experiences and the effects of trauma on victim-survivors more broadly. Common impacts include substance addiction, eating disorders, addiction to abusive relationships and chronic self-harm. These symptoms, Osborne-Crowley argues, were “weaponised against Epstein’s survivors on cross-examination at trial, in an attempt to undermine their credibility, their morality, their memories”.

“I can tell you that some combination of these symptoms will show up in every single trauma survivor,” writes Osborne-Crowley.

So even though our society stigmatises and shames them – as Maxwell’s defence team did – the evidence is clear: the presence of these difficulties in someone’s life is not proof that the trauma they are describing didn’t happen. It is proof that it did.

Almost a year before the interview, Osborne-Crowley arrives at 3.04am on day one of the Maxwell trial. She queues outside the Manhattan courthouse alongside other journalists, members of the public and professional “line-sitters” wrapped in bright yellow blankets, armed with thermoses and sleeping bags, who are paid an hourly rate to hold a spot.

When the building opens, an officer reveals that only four seats have been set aside for journalists. The rest will only have access to spare rooms down the corridor, where proceedings will be relayed on a tiny video screen. Moreover, the judge has determined journalists may not use laptops or electronic devices of any sort, so the court reports are old-fashioned shorthand notes, with pad and pencil.

Osborne-Crowley decides that for the next four weeks, she will arrive at 2am to secure a seat in the courtroom. She writes:

For weeks after this I will sit within two feet of Ghislaine Maxwell. I will get to know her mannerisms, her moods and her habits intimately. But for now, I am seeing her only on a screen and I do not get a fraction of a sense of who she is.

A ‘pyramid scheme’ of sexual abuse

In December 2021, Ghislaine Maxwell – daughter of financial fraudster and one-time British press baron Robert Maxwell – was convicted on five of six charges against her, including sex trafficking a minor, in relation to her association with Epstein. Four victim-survivors of the Epstein sex-trafficking network testified in court, including “Carolyn”, who died in 2023, aged 36.

The jury found the wealthy socialite had manipulated girls as young as 14, recruiting them into a “pyramid scheme” of sexual abuse. As assistant US attorney Lara Pomerantz told the court in her opening statement, “as an adult woman”, Maxwell provided “a cover of respectability for Epstein that lulled these girls and their families into a false sense of security”. She “lured” victims with the “promise of a brighter future, only to sexually exploit them”.

Maxwell continues to appeal her conviction, most recently on the basis she was granted immunity from prosecution under the terms of a 2007 plea agreement with Epstein.

The Lasting Harm reveals how trauma shaped the lives of the four victim-survivors who testified. It tells the stories of other victim-survivors, whose testimony was excluded from the prosecution case. And it considers the impact of vicarious trauma on journalists, produced by long hours spent “interviewing people about their darkest moments”.

On two occasions during the writing of the book, Osborne-Crowley checked herself into a mental health facility with clinically diagnosed PTSD, including structural dissociation and memory blackouts. Clinicians told her that her vagus nerve (responsible for digestion, heart rate and breathing, among other things) was malfunctioning. She was re-experiencing traumatic memories “as though they are still happening”, and her body was responding accordingly.

But no such care was extended to the victim-survivors who testified in the Maxwell case. Instead, defence lawyers would wield trauma as a weapon in the courtroom.

Memory on trial

The entire point of cross-examination is to attack a witness’s memory and integrity, in ways that – as clinical research long ago established – will dangerously escalate, not heal, their trauma.

In the Maxwell case, defence lawyers accused witnesses of fabricating lies in exchange for lucrative media, publicity or book deals, by acting as “touts” for victim-survivors, or manufacturing sexual abuse claims in exchange for a “special” US visa.

One controversial expert testified that sexual abuse memories could be “falsified” and “implanted”. Lawyers claimed witnesses had been manipulated by federal prosecutors, FBI agents and self-interested civil attorneys anxious to “shake the money train”, securing a “big jackpot” from the Epstein Victims’ Compensation Program.

Lawyers also focused on small, peripheral details in the testimony to surface tiny inconsistencies. For example, when Maxwell met the witness “Jane”, then a 14-year-old at summer camp, the cross-examination focused on whether Maxwell was walking by with a dog, walking a dog with Epstein, or using the dog as a ploy to approach the teenager.

The line of attack did not address the substantive allegations of child sexual abuse, but it impressed the media gallery. “This really isn’t good,” a journalistic colleague confides to Osborne-Crowley. “That’s way too many inconsistencies.”

The lawyers’ courtroom playbook is depressingly consistent across all types of sex offences, in all countries that rely on the spectacle of the jury trial – underpinned by a bitterly adversarial legal system – to deliver “justice” for victims.

Osborne-Crowley’s book carefully documents the unedifying clash of high-priced lawyers, setting it against a social context in which access to justice is increasingly unaffordable for most, and the conviction rate for sex offences is as low as 1%.

Yet, she never takes the next logical step, which is to conclude that the adversarial system and jury trial is not fit for the purpose of trying sex offences.

Focus on victim-survivors, not billionaires

In recently unsealed court documents, the identities of 150 public figures who moved in Epstein and Maxwell’s social orbit were made public. They included former US presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump, (the latter already on the record in 2002 calling Epstein a “terrific guy” who liked “beautiful women […] on the younger side”), and scion of the British royal family, Prince Andrew.

Former Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz, also named in the unsealed court documents, released a half-hour YouTube video warning about defamatory imputations that might arise from any implication of guilt by association arising from the appearance of a name on a “list”. Dershowitz helped Epstein negotiate the 2008 plea deal.

But Osborne-Crowley’s book is not concerned with “billionaires or private jets or Prince Andrew”. Her primary focus is on the girls as young as 14 who were selected for their vulnerability. Epstein and Maxwell believed they would never possess the strength or credibility or social power required for their testimonies to be believed in a court.

Yet, the spectre of systemic failure is inextricably related to the Epstein case.

Epstein was first arrested for child sex-trafficking as early as 2008. But the district attorney in the US state of Florida approved a plea bargain that allowed Epstein to escape with a minor solicitation charge: essentially treating child victims of sexual abuse as adult professional sex workers. The deal also granted legal immunity to Maxwell. It is currently the basis of Maxwell’s appeal against her 20-year prison sentence.

In 2017, ten years after his first arrest, the district attorney who had approved Epstein’s deal was appointed Labor Secretary to then President Trump. This prompted the Miami Herald to green-light an investigation, by journalist Julie Brown, who tracked down 60 of Epstein’s alleged child victims. Brown’s work prompted the New York district attorney to investigate. Epstein was charged with child trafficking offences in 2019.

Vanity Fair writer Vicky Ward also attempted to break the Epstein story as early as 2003, but says the magazine spiked her interviews with victim-survivors. (The then-editor Graydon Carter has disputed this reasoning, saying her three sources were not on the record as she has claimed.)

Osborne-Crowley befriends both journalists while covering the trial: Brown even becomes a mentor.

For journalists, there are enormous risks attached to pursuing, investigating and telling stories of this sort. While the advent of #MeToo removed much of the cultural stigma that accompanies speaking out about sexual abuse, it has been followed by a backlash of defamation actions, frequently dubbed “#Metoo litigation”.

Human rights lawyer Jennifer Robinson, interviewed for Osborne-Crowley’s book, explains what happens when perpetrators weaponise the legal system to pursue their victims. She also explains how the burden of legal costs falls on victim-survivors and journalists who try to tell their stories.

Memory, trauma and inconsistencies

Leading defence lawyer Bobbi Steinem tells the court,

Ever since Eve was tempting Adam with the apple, women have been blamed for the bad behaviour of men, and those women have been villainised and punished.

It was surprising the defence did not argue Maxwell was also a victim, manipulated by Epstein. Instead, it adopted the traditional courtroom strategy of placing the victim on trial and attacking the credibility of victim-survivor memory.

The most important witness for the defence was the controversial memory expert Elizabeth Loftus, who claimed to have “proven the existence of false implanted memories”. She has testified or consulted with the defence on behalf of Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Michael Jackson, Ted Bundy and O.J. Simpson.

The ideas presented were derived from memory experiments conducted in laboratory settings. These included the post-event suggestibility of witnesses who claimed to see Bugs Bunny (a Warner Brothers character) at Disneyland. This is where the defence case fell down. As prosecutor Alison Moe reminded the jury, this is “not a case about Bugs Bunny” – and core memories of traumas such as child sexual abuse are stronger than other types of memory.

Moe asked the defence expert, in an exchange that seemed to turn the case around, from the media’s perspective, at least:

“People may forget the peripheral details of a trauma event, right?”

“That can happen, yes.”

“But the core memories of a trauma event remain stronger, right?”

“I probably agree with that.”

The Lasting Harm is not a comfortable read, but it’s an important one.

Camilla Nelson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.