Shaun Peterson hadn’t thought much about Abraham Lincoln’s love life until around 15 years ago. That changed when he read Gore Vidal’s 2005 Vanity Fair article about “The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln,” C.A. Tripp’s controversial biography that dared to make connections other historians had long set aside concerning his friendships with other men.

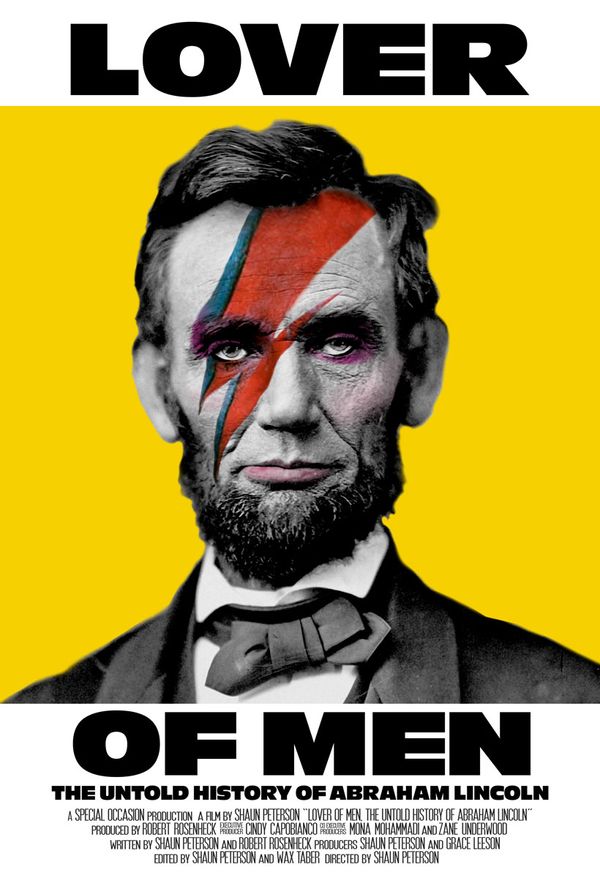

The title of Vidal’s piece places the question front and center: “Was Lincoln Bisexual?” Nearly 20 years later, Peterson’s documentary “Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln” revisits that question with ample visual evidence. But the first image drawing our attention is the poster’s illustration, featuring Lincoln’s face dashed with David Bowie’s signature red lightning bolt from his album “Aladdin Sane.”

“It's a striking image, sure,” Peterson told Salon in a recent video interview, adding, “It's very punk rock. But I think Lincoln and Bowie share a lot of the same behaviors in their past.”

The accepted history of Lincoln’s love life is that he was awkward with women, but eventually courted and married Mary Todd Lincoln, and had four sons, three of whom died young. But Tripp and others scrutinized the whispers in the margins that cast Lincoln’s relationships with men in a different light.

Lincoln's first intimate experience may have been when he shared a cot with Billy Greene, with whom he worked in a New Salem, Ill., store after moving there in 1831. He was said to have grieved more passionately for Col. Elmer Ellsworth, the first Union soldier to die in the Civil War, than for his sons. Capt. David Derickson served as Lincoln’s bodyguard and shared a bed with him.

But no relationship was more central to Lincoln’s life than his bond with Joshua Speed, a handsome store owner in Springfield, Ill., with whom the man who went on to be the 16th president of the United States shared a bed for four years. Vidal, repeating other historians’ assertions, pointed out this was “not necessarily, in those frontier days, the sign of a smoking gun — only messy male housekeeping.”

“Nevertheless,” Vidal added, “four years is a long time to be fairly uncomfortable.”

Peterson designed “Lover of Men” to connect Lincoln’s suppressed history to the larger queer experience in America and human history. Through his lens, Lincoln becomes an anchor to look at society’s view of same-sex relationships back to antiquity and connect it to modern views of sexual fluidity and legislative pushback via anti-LGBTQIA+ bill proposals in Congress and state legislatures.

In our conversation, we discussed these choices and Lincoln’s enduring significance as a political and historic icon.

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Before we dig into the documentary, I read your filmography and noticed that you've done a lot of video work. So that leads to a question about your decision to this very recognizable Bowie album cover image over Abraham Lincoln’s face. Can you talk about the meaning of that? That's the first thing people will notice.

Yeah, sure. I think it's a great comparison, because David Bowie had lots of love affairs with men, married a woman, had children, never, ever defined himself, never even called himself bisexual. He's just a man that fluidly went through life finding things that he enjoyed and ways to connect. And that's the kind of the point of the movie.

The word homosexual, the word heterosexual, were literally invented in the 1870s . . . Before that, things were very fluid. Even the idea of gender identities are all very new concepts. So the fact that Lincoln had all these different men that went in and out of his life, these loves, but also is married — because marriage culture was very important – makes it a really good analogy. What I find fascinating today, too, is the Gen Z is also hearkening back to the past with a more fluid life where these labels and binaries didn't exist.

Since we’re talking about Gen Z: Right now, there is this concerted effort on the part of the right wing to suppress history on a larger scale than the previously existing level of suppression that is discussed within “Lover of Men.” What is the importance of this coming out right now?

Well, we definitely wanted this to come out right before the election for a reason.

One of our scholars, Dr. Lisa Diamond, speaks about how much empathy the film evokes. Certainly it's a hotbed film, but at the same time, I think it's a love story. And it's a story that asks people to have an open mind and see with empathy that these Gen Z kids aren't just part of some trend. That the trend of loving someone that you love, regardless of what gender they are, what sexuality they are, is human existence.

Another of our scholars, Michael Bronski from Harvard, said it well when he said that people's impulses throughout history have always been the same, but how we define those impulses changes throughout time. Right now, we're in a particularly conservative time, and what we're asking the audience to do is . . . look at our past in order to find a way forward. Certainly the hundreds of anti-LGBTQ laws that are on the ballot and in state legislatures right now is definitely what we're focused on, too.

Now, if you were just to look at the title — it's provocative. And there's a lot of explanation about how this element of Lincoln's life and his identity was suppressed. But also, getting into the film, you take a look at antiquity. The film continues long after his assassination, and you intentionally make this connection between this history and what's going on today. Was that originally your intention, when you first decided that you were going to film this story?

Look, I've been researching the Lincoln part of it for 15 years. But I learned a ton of making the film and talking with all these scholars about human sexuality and the history of it. So that came in as we were first crafting the original concept. And as I started doing more research . . . that became a big component of it. But I think it was also important to be like, "OK, we're making this case. Hey, everyone, here's all these photos of these queer couples in the 19th century. We've always been fluid. . . . What went wrong? How are things so different today?" So we really had to tell that story of when things started to go off the tracks there, when the binaries were created, when the early cycle of psychiatric community took it on. Then the modern church took it on. That was all part of the process and the research of the film.

You said you've been researching this for 15 years, so let's go back to 2009. Did you know about this story then or was it one of those situations where you heard about it and decided to find out more?

Well, I read a Vanity Fair article that Gore Vidal wrote about Clarence Tripp's book, "The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln," and that just is sparked my imagination. This has been going all the way back to the 1925 [edition] of Carl Sandburg’s book, where talks about "streaks of lavender, and spots soft as May violets."

. . . I just kept trying to find ways to tell the story. And then it occurred to me during the pandemic, that I should make a documentary about this. I should really set the record straight. Because whenever I pitched it to people, they're like, "You know what? This doesn't make sense. No way. There's no way he was queer." And I thought, "OK, well, I'm gonna have to prove this to people, to set precedent for it."

We went to great lengths to go into the Library of Congress, dig out documents, go to Brown University . . . you see in the film, these letters that we pull out. A lot of these have never been seen before. And one of the things we're trying to point out is that, like when you see a letter where Abraham Lincoln is a lawyer, a very dry writer is writing very eloquently, very lovingly to another person. You know a love letter when you see it. You know in your heart, and you feel the love letter as it comes out. And I think that was important for us too.

Something else that this film does really is connect the gaps in the histories we’ve learned that seem so obvious. I don't know if you had some thoughts just in terms of how you approach filmmaking in a way that that fills in these gaps of history that have been edited out.

Well, that’s what I think is so great about making a movie about this topic, right? On the fringes of academia, there's been writings about it. Once in a while, an article will pop up, and people will lose their mind over it. But to see it visually, like with pictures . . . I really drew out that section where you see all these queer couples in the 19th century, photo after photo after photo. Bear in mind, these are men and women that are going into public photo studios. They're not taking selfies alone. They're going into a studio and they're embracing each other. And it just shows you, time and time again how this wasn't a big deal at the time, that this kind of same-sex affection and love and physicality existed. The opportunity to see that on screen, to experience it in a film with music and to feel the emotionality of it was important.

That's what drew me to expanding the story. And then . . . I wanted to tell a love story where we see these affections that happen. You know, you can read these things and they feel dry and academic, but when you see them come to life, and you see these young people —I mean, I really want young people to see the film. And when you see this, this young couple, Lincoln and Speed together, having these queer moments, sleeping together, enjoying each other, intellectually connecting, I think the young people will see themselves in these figures in a way maybe they hadn't before.

Lincoln is claimed by both sides of the partisan divide. What do you think it is about him that makes him so such a celebrity among American presidents? And how do you think that, either through coded language or overtly stating that he was in same-sex relationships, how do you think that might have played into that popularity whether people knew about it or not?

Look, I mean, he’s the person that's credited for saving the nation at all cost. He kept the Union together.

Everyone loves Lincoln, and he was such a meek man. And as you know, history shows he literally made his cabinet [from] his political rivals. This would be unheard of today. You know, the idea of [Donald] Trump bringing Bernie Sanders into his cabinet would be preposterous, but Lincoln did that. That's how open-minded he was, and that's what everybody loves about him.

But whether people at the time knew or didn't know, well, we show evidence that lots of people knew that Lincoln, while in the White House, was sleeping with his bodyguard. A lot of scholars will say, "Oh, it was common to share beds when men were didn't have a lot of money." Well, maybe when Lincoln and Speed first slept together, it was financial. But for four years? That was not a financial decision. He was a legislator and a lawyer. He's making plenty of money. He wanted to sleep together, and people in the community knew, and it wasn't a big deal. All the superior officers of Captain Derickson knew he was wearing Lincoln's night shirts and sleeping with him at night, and it wasn't a big deal.

And that's what we have to really realize, that the behaviors of the time are very different than they are today, and it was accepted.

In New York, "Oh, Mary" – a play starring “At Home with Amy Sedaris” castmate Cole Escola as Mary Todd Lincoln – is running on Broadway.

Yeah.

I don’t want to ask you specifically about that, but rather the creative habit of approaching Lincoln’s life stories from an array of directions including fictionalizing him as a vampire slayer. Why was it important to you to tell this story as a documentary versus dramatizing it?

A good question. I mean, I certainly considered fictionalizing it. But again, this story is so . . . I mean, no one was trying to convince people that he was a vampire hunter. Everyone knows that was just fun, but to convince people that Lincoln loved other men was going to take a burden of proof. And that's why we went to great lengths to really find the documented evidence.

I was going to have to say, "This seems far-fetched, but bear with me here and let me tell you the story of not just Lincoln, but of Lincoln's time." And I think it was important to do that in a documentary, to really set the tone.

I think when you're a kid in school, and you think about Abraham Lincoln, he's very stoic and he's very serious. But to think to Lincoln as a human being, who had love in his heart? He loved these men, he loved his wife. You can have both throughout your life.

And I think we're seeing with this younger generation that's the way it can be. You can love different people throughout your life . . . And I think we want to get to a point where we accept that and not make it illegal to love. And the fact that we're at a place where love could be illegal again is unbelievable.

So I ask people to say our greatest president, one of the greatest Americans that ever lived, also loved people from both sexes. And as one of the scholars in the film said, if you can accept a queer Lincoln, you can accept all queer people.

"Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln" is playing in limited release in theaters nationwide.