“Soul Train” was the place of love, peace, and of course, soul. Broadcast nationally from 1971 through 2006, it was one of the longest-running TV shows in history — with the longevity of this cultural phenomenon attributed to creator and longtime host Don Cornelius.

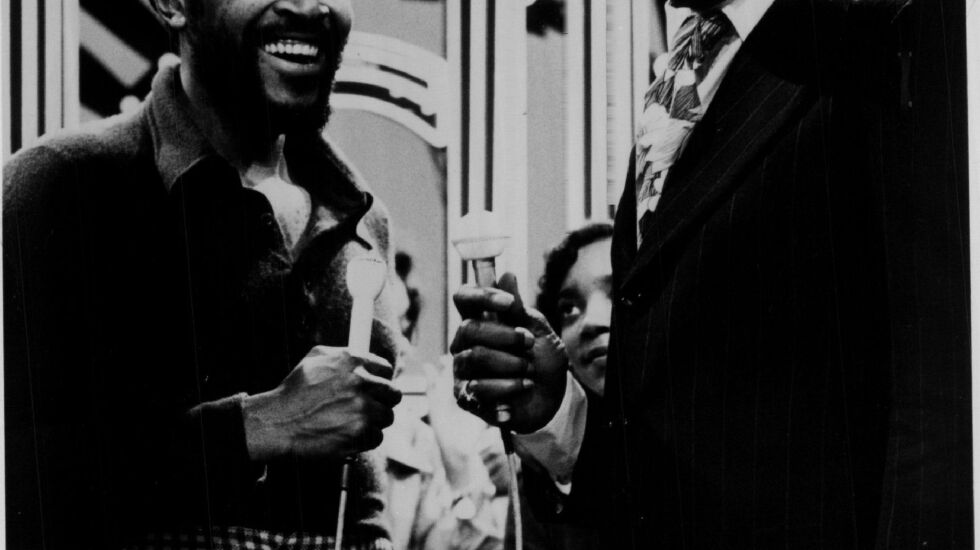

In 2011, Chicago celebrated the 40th anniversary of the show’s first nationally syndicated episode with a free concert in Millennium Park.

“That was incredible,” said former WBEZ host Richard Steele, a longtime radio personality and friend of Cornelius. “It was the 40th anniversary of the program, but it was also a celebration of Don Cornelius. That had never happened in Chicago — celebrating him even after all of his successes. And ... he was almost in tears, and he was not a guy to really shed tears.”

Steele was an emcee at the event.

Besides Cornelius himself being a product of Chicago, there’s another reason why this celebration was monumental: because it was Chicago that gave birth to “the hippest trip in America.”

Before becoming a nationally syndicated show, “Soul Train” began as a local show in Chicago. And this week, Aug. 17, marks 53 years since it aired for the very first time.

A more grown-up dance show

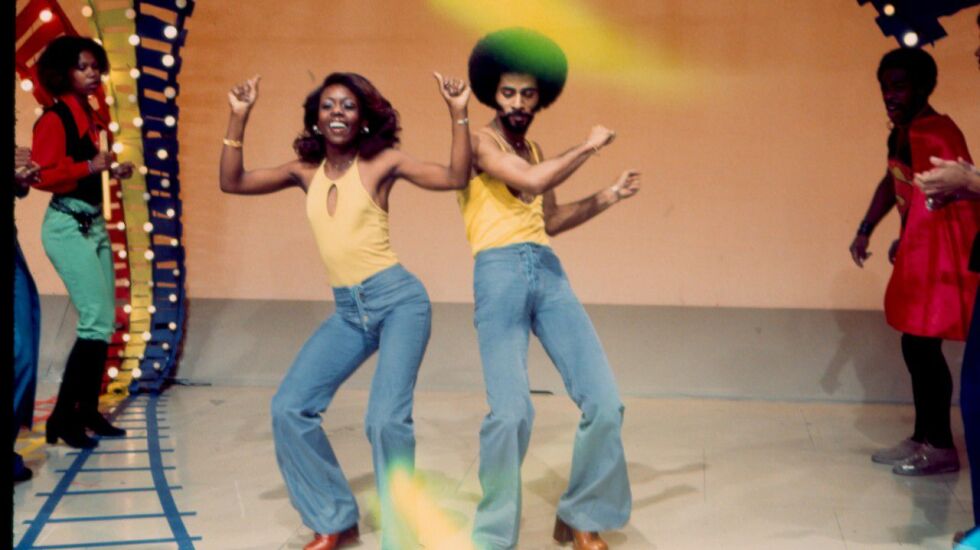

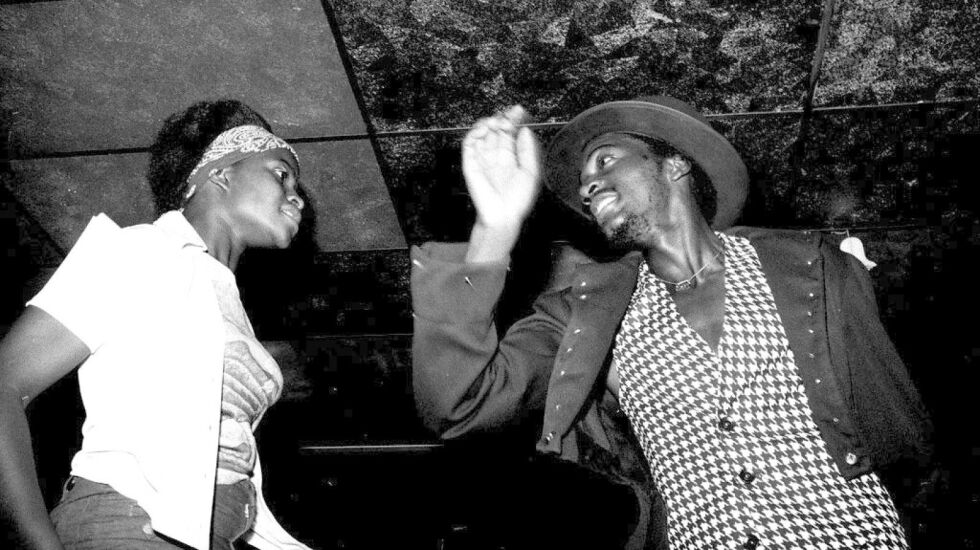

Back in 1970, young people lined up around the block of the Chicago Board of Trade building to be part of the first airing of this new dance show. They’d pack the tiny WCIU studio, along with mostly Black creatives who were invited to showcase their talents on TV.

Artist Michael Griffin was one of those creatives. He was part of a group of designers and models named Les Ménage.

“I was known as a good dancer and someone who dressed well, which is kind of how those friendships began,” he said. “Our group was pretty much well known in the Chicagoland area.”

Being on the scene is how he got to know Clinton Ghent — a Juilliard-trained dancer and choreographer who grew up with Cornelius. Cornelius tasked Ghent with finding hip people for the show, which was an extremely essential role. Ghent invited Griffin’s group on to “Soul Train” to model their clothing designs.

Ericka Blount Danois, author of “Love, Peace And Soul,” says the show allowed the city’s young people, like Michael Griffin, to become the show’s stars. And that was part of the magic.

“It was in this small space, like 10-by-10, no air conditioning,” she said. “But these kids were so talented that it took off. And also, just being able to sort of see yourself on TV, the kids felt like they were local celebrities, because they were.”

The idea of a dance show wasn’t necessarily new. There were other dance shows in Chicago, “Kiddie A Go Go” and “Red Hot and Blue.” But Cornelius was motivated. He wanted to show Black youth in a way that the national media wasn’t portraying them at the time. His idea was to reimagine what a dance show could be: make it fresher, edgier, cooler. And pairing the city’s young people with that vision proved to be a winning formula.

“This dance show that he created on WCIU Channel 26 was a little bit edgier,” Danois said. “These were teenagers, a little bit older, and they had dance moves that were good.”

On top of this edgier approach, Chicago was already a music city, especially for Black musicians. So much of the most popular music of the 1950s and ’60s, leading up to the “Soul Train” launch in 1970, came from the city.

“Etta James, Muddy Waters, the Dells, Chuck Berry — all of these people in this sort of place that is not New York, but is a music town,” Danois listed. “Earth Wind and Fire, Curtis Mayfield, in terms of businesses, also, Sam Cooke … and Curtis Mayfield creating their own labels.”

The role of the Black radio celeb

Cornelius’ rise in entertainment was swift. But it likely started with a chance encounter while working as a Chicago police officer. Legend has it that he was discovered by an executive at radio station WVON during a traffic stop, when the exec was blown away by Don’s voice and suggested he come work at the station.

Cornelius started working at WVON in 1966, and at the time, the role of Black radio personalities mirrored that of celebrities. As migration to Chicago from the South continued during this time, communities of Black folks who loved their radio personalities continued to swell.

“Chicago was the mecca,” said Melody Spann Cooper, chair and CEO of the company that owns WVON — the first station in Chicago to cater to Black audiences.

Her father, Pervis Spann, was one of the city’s most well-known names in radio as well as the station’s co-owner.

“They all had monikers,” she explained. “You had E. Rodney Jones, ‘The Mad Lad,’ who was the program director; you had Bernadine C. Washington — she had the biggest women’s club in Chicago, 3,000 women strong. … But all of them have their own special identity, special brand, and they brought their own DNA, which made it so powerful.”

Steele, Cornelius’ friend, says he was ambitious and took full advantage of how well-loved WVON personalities were in the communities.

“WVON was the killer radio station at that point,” he said. “And Don was a news guy who filled in as a disc jockey from time to time. Because ’VON had such high visibility, it gave the personalities visibility, even the news people.”

Cornelius had music sets in high schools across the city called record hops. Those events created his audience for the show he would create.

In addition to radio, Cornelius already had ties in television. He hosted a daily news show called “A Black’s View of the News” at WCIU, the TV station where “Soul Train” would air. Don used $400 of his own money to produce the pilot.

“It became a success,” said Steele, about the start of the local show. “The first people he had on were the Impressions and Staple Singers. … And these kids were dying to be on television, show their dancing skills, and be there on ‘Soul Train’ with Don Cornelius.”

“Soul Train” wasn’t the only show in the country, though. Every major metro area had a dance show with local teens clamoring to be on it. But there was something about “Soul Train” — and Cornelius — that made this particular show stand out.

“He was cool,” Steele said. “Don went to DuSable High School. … And if you knew him, you wouldn’t say, ‘Oh, this is the erudite television personality.’ No, he’s Don from the hood.”

As a host, Cornelius’ connection with the audience was effortless. And, it was authentic.

“With him, since he was from the inner city and from the community, he connected directly. He didn’t have to stretch to do that,” he said. “He knew who everybody was, what they were about, as you do when you grew up in a community and you’re a person who’s involved a lot.”

And it’s that culture, that Chicago cool, that took “Soul Train” far past the walls of its 10-by-10 studio. In 1971, just a year after being a local show, Cornelius got a syndication deal and created a new version of the show in Los Angeles. There, it became a national phenomenon.

Even after Cornelius moved out to Los Angeles, he continued to produce a local version of “Soul Train” in Chicago. Ghent, who helped him launch the original broadcast, hosted the Chicago show until 1976 (with reruns airing until 1979). And kids still lined the block for that one, too.

A long-lasting legacy

Although “Soul Train” ended in 2006, its legacy — and that of its founder — did not.

“It was fitting that Don Cornelius, from here, would start something like that,” said Duane Powell, a DJ and music historian. “Because he was literally seeing the vibrancy of this soulful culture right where he’s from. And I do see it [now].”

Here in Chicago, Powell says there are new young creatives who are connecting with each other, taking control of their own futures, and creating resources to display Chicago talent to the world.

“I think that millennial-wise, a lot of millennials have taken up the mantle of a lot of Chicago goodness and have been really, really forging new paths globally,” he said. “So I do see that era has shaped … where we are now.”

He’s really proud of creatives — like Chance the Rapper, Vic Mensa and Noname — who are doing the very same things that people like Cornelius did in his day. Because of this, he wants young Chicago to know about the city’s full influence.

“There’s so much of Chicago history that has not been really covered and talked about,” he explained. “We still are this really untapped market. And just how influential we were all over the world. This is the home of house music, this is the home of the modern blues, this is the home of gospel.”

And, Chicago is the home of soul.

Arionne Nettles is a lecturer and director of audio journalism programming at Northwestern University’s Medill School.