The title of Louis Fratino’s Satura at the Centro Pecci comes from a term in Latin, Satura Lanx. This was a plate of fruits that were intended for the Gods. It’s in this context that Fratino’s engagement with queer history, Italian landscapes, and the body itself, seem best understood. Throughout the images in Satura - paintings, lithographs, exploratory drawings - there are breadcrumbs leading towards queer cultural history, their offhand nature providing the show with a kind of 'if you know, you know,' extra dimension.

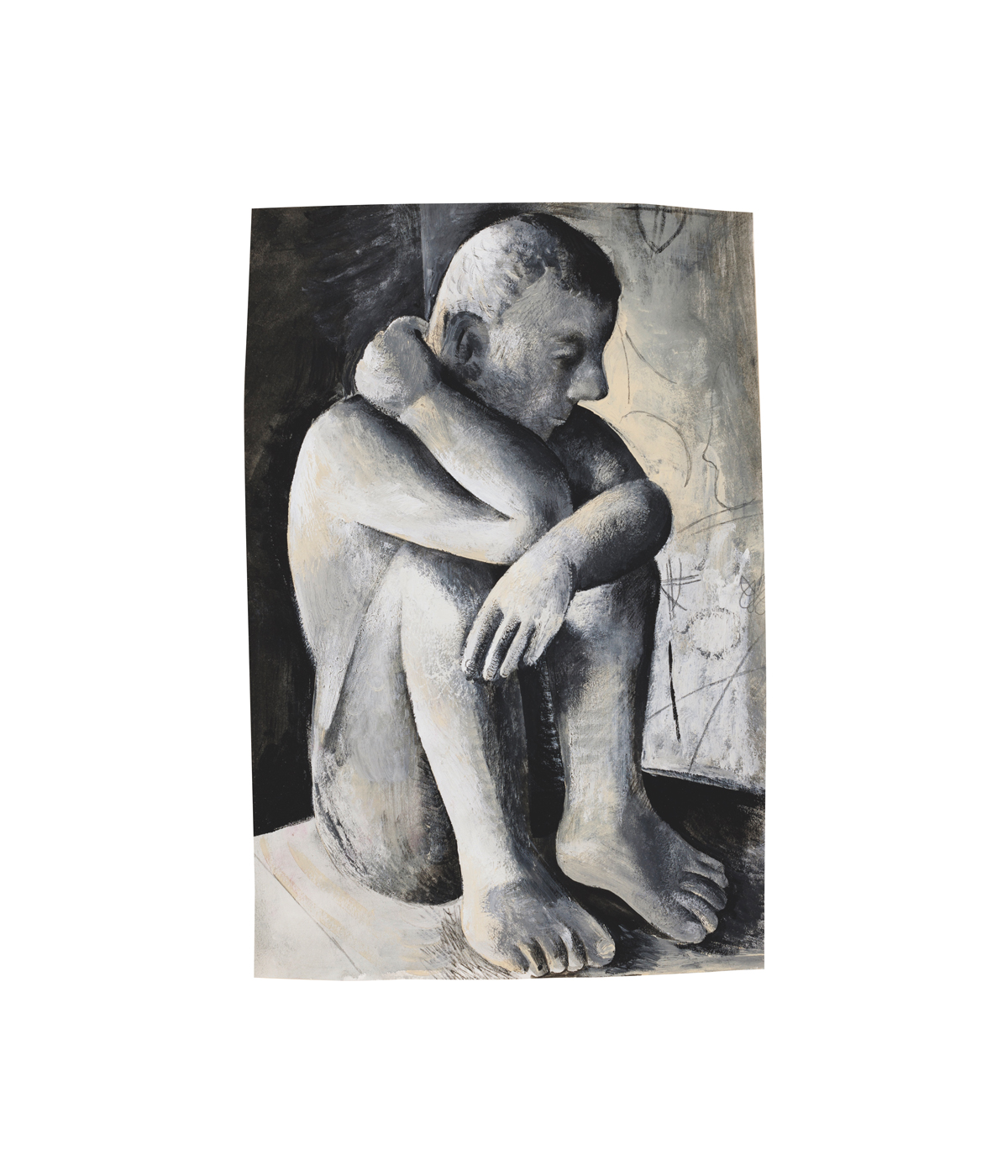

These can be as simple as paintings like View of Monte Cristo (2020) containing a book with Frank O’Hara’s name on it by an open window, to the stark shadows in the lithograph Figure After Dino Pedrialli (2020), a photographer Pasolini commissioned to spend two days with him in 1975, just days before his death. Pasolini seems like a perfect fit with Fratino’s body of work - this exploration of intimacy and the body in a way steeped in not just an emotional understanding of queerness but a historical, theoretical one as well.

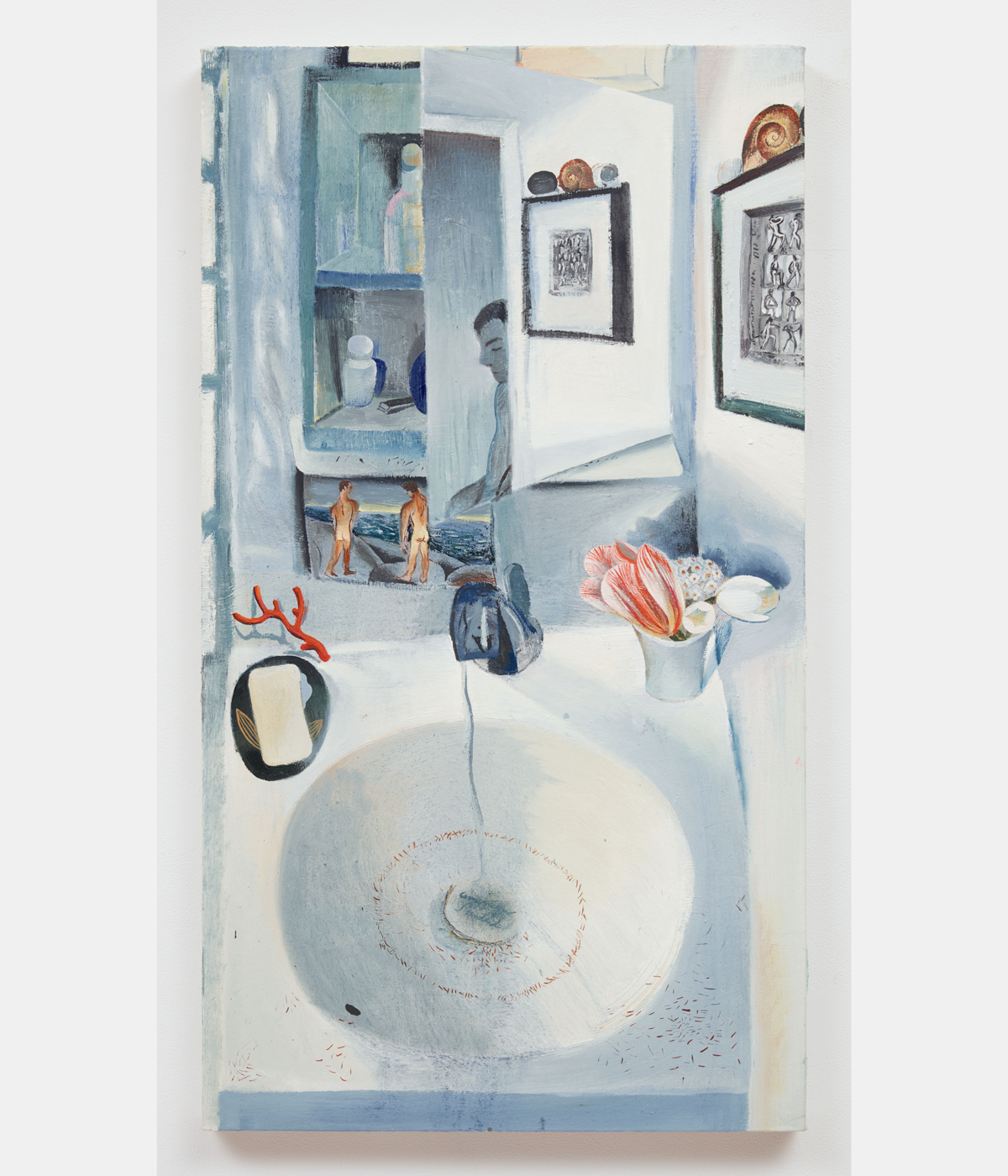

The multitudes through which Fratino grapples with queerness becomes mirrored in the space itself; with the images opposite one another in a long, winding corridor. On one side of the exhibition are images that explore interiors and domestic life, and opposite them are portraits of the natural world, something more vast and wild. What makes this effective is that, rather than simply showing that intimacy would function in one sphere but not another, Fratino instead shows how fluid the word can be. In View of Monte Cristo, a nude body is almost camouflaged amidst trees, but visible through the space where Fratino situates us - resting on the ledge by these open blinds are the O’Hara book, denim shorts, and a pencil. Fratino’s eye for detail, something that feels almost classically, academically ‘painterly’ in images that draw on the tradition of still life, as in You and Your Things (2022). And what this almost obsessive eye for minute details does, before it veers into feeling too academic and referential, is smuggles references to queerness into our understanding of art history. It’s tempting to consider this through the representational refrain “we have always been here,” which, although true, flattens what makes the work dynamic.

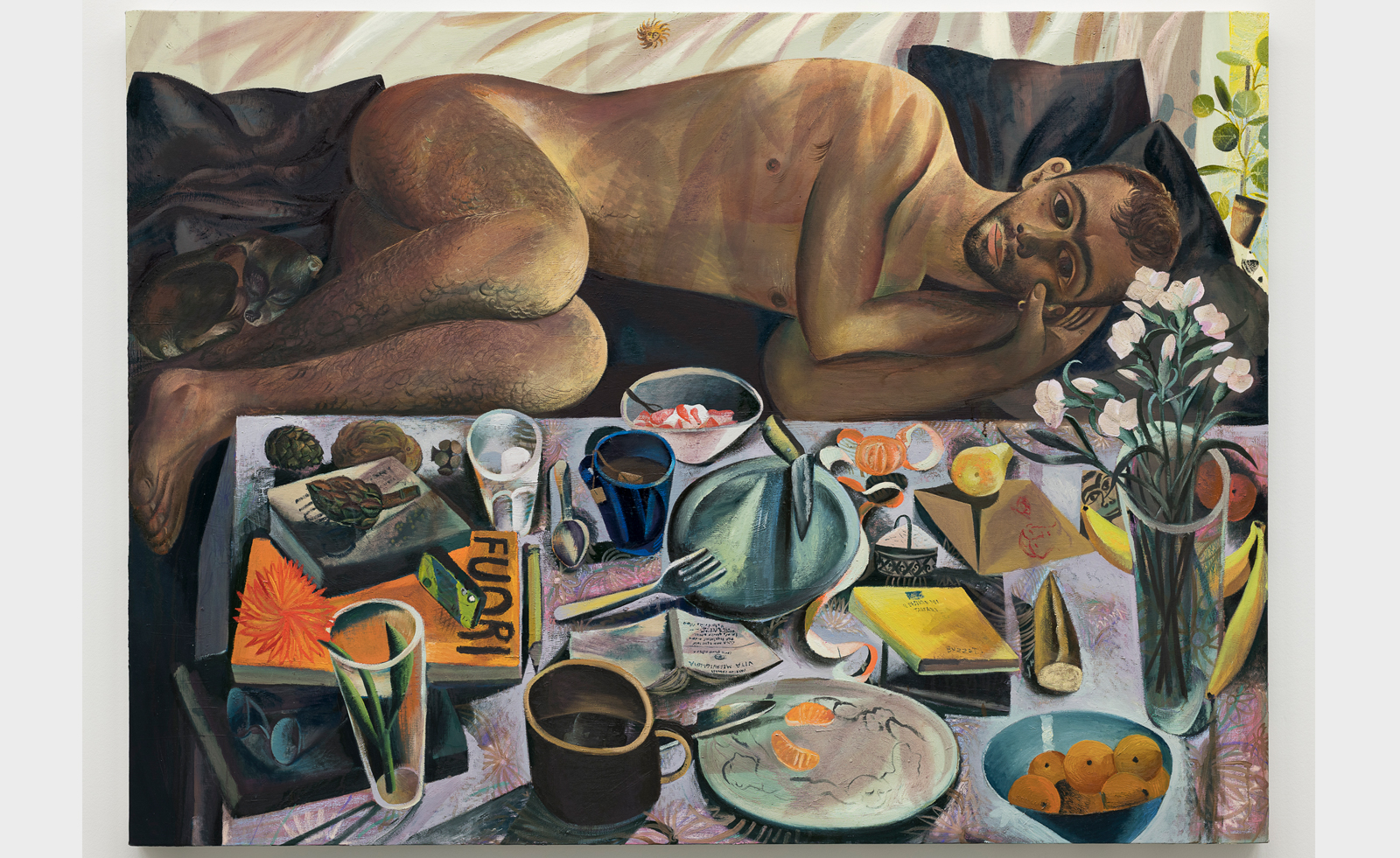

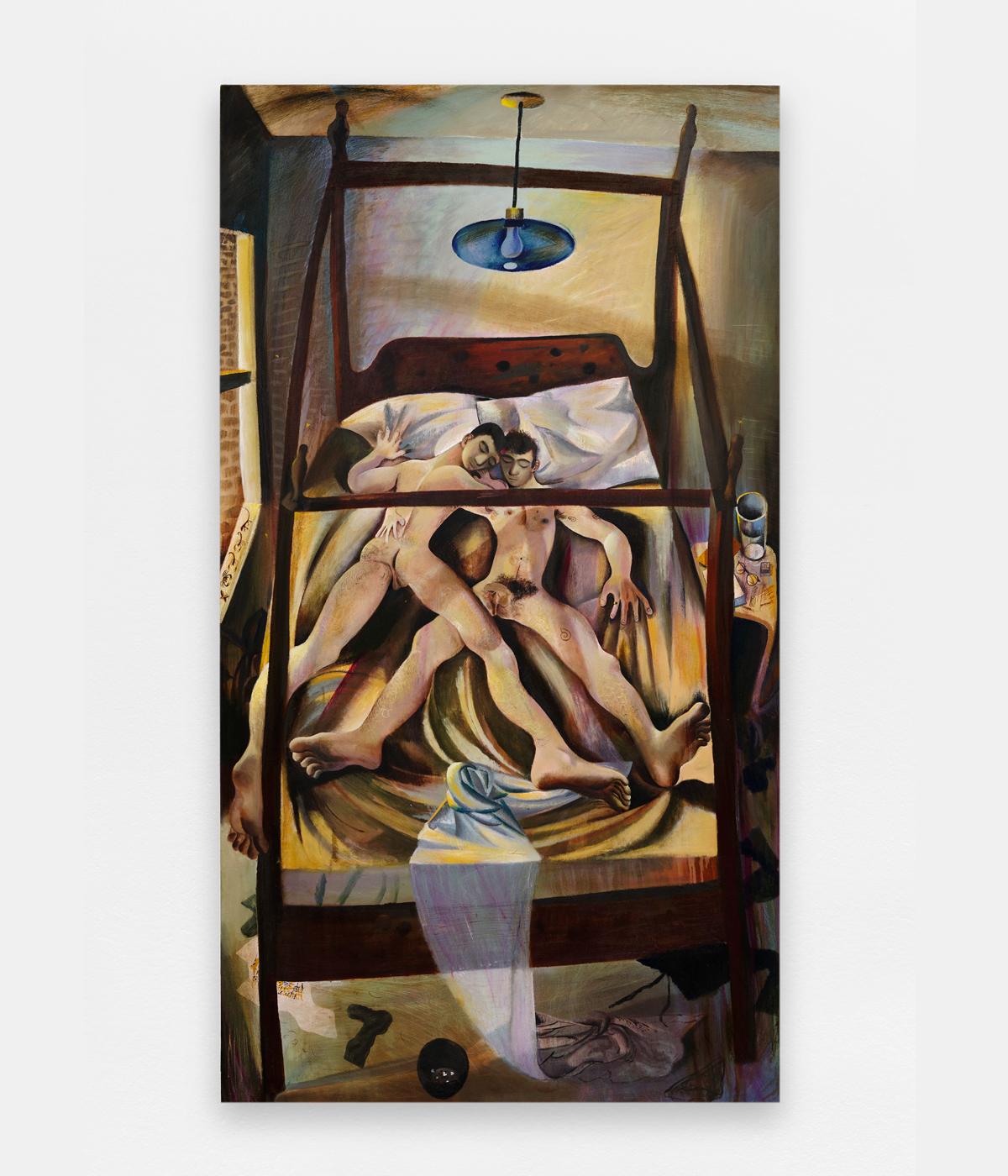

What feels like the heart of Fratino’s work isn’t merely the presence of queerness as a representational marker to point to, but the energy with which it infuses the exhibition, as if - like the Satura itself - it were somehow divine. Along with View of Monte Cristo, The Locust Trees (2024) offers an almost Edenic landscape of sprawling foliage and, buried in its depths are cruising bodies; Fratino’s work is imbued with a sense of possibility, an urgency that feels like it lives in the queer body specifically. This doesn’t always land perfectly; putting Fish Market (2020), a painting of fish together in a confined space next to Arci Bellezza (2023), a painting of bodies in close proximity feels like a curatorial leap that doesn’t quite stick the landing in terms of how it wants to present these bodies in relationship to one another and the natural world. If anything it undercuts the propulsive desire that gives Satura the impact that it has. This moves not just through embodiment - although this exists in much of Fratino’s work, and in placing images of bodies having sex, or striking erotic poses inspired by 20th century gay lifestyle magazines alongside the more traditional images of still lifes and landscapes liberates the idea of queerness, and queer desire in particular, as something to be othered - but through both interior and exterior spaces.

Throughout Satura, the body becomes an extension of the space, whether in the almost camouflaged nudes in some of Fratino’s landscapes, and in May (2020), where a body reflected in a bathroom mirror exists in the same space as an image nudes on a beach, and a series of strongman poses ripped from the pages of lifestyle magazines and early pornographic films, we see space becoming an extension of the figures in the space, filled with desire - sometimes furtive or unfulfilled, sometimes consummated - and, like the Satura Lanx once given to the gods, offers up something that is achingly human.

Louis Fratino 'Satura' is at Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato, Italy until 2 February 2025