Like many film directors, Osgood Perkins spent much of his youth making home movies on the family camcorder. “We did a lot of takes on Jason Voorhees,” says the Longlegs filmmaker today, over Zoom, referring to the machete-wielding killer of Friday the 13th. “We’d put a hockey mask on top of a gorilla mask and then he, this character, would lurk around and strangle people.” So far, so teenage boy. “I guess the difference for me was that I’d be filming in the kitchen and the door would open and it’d be my dad.” Dad to Perkins, by the way, is Norman Bates to the rest of us.

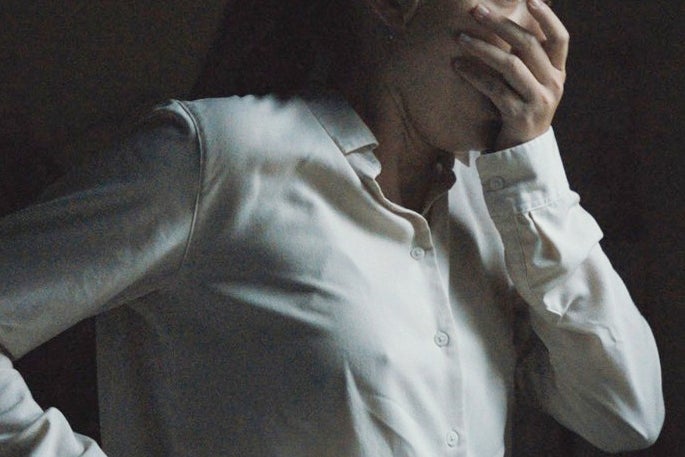

The resemblance between Perkins and Anthony, the brooding star of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, is undeniable. Perkins shares his father’s square jaw and shelved brow, the jutting cheekbones and deep-set blue eyes. It’s a face so distinctive that it might seem inimitable were I not seeing it copied and pasted here today. For a long time, though, physical attributes were all they shared. “My dad was not the most knowable person,” says Perkins, who was 18 when his father died of Aids-related pneumonia.

The home videos, recently unearthed by a family friend, are one of the few times that Anthony was captured by his son’s lens. Physically speaking, that is. Metaphorically, decades after his death, the actor continues to loom over his son’s work, a spectre that is, if ever out of sight, never out of mind. “He didn’t reflect me very much, so I think I was always going to be looking for a connection to my dad – and movies are a good place to look,” says Perkins, now 51. “Maybe I’ll find out something about him as I find out something about myself while going down that path.”

Perkins sees his films as autobiographical and his characters as surrogates for himself. His debut, 2015’s The Blackcoat’s Daughter, cast Kiernan Shipka as a teenager at a Catholic boarding school turned satanic by the prophetic death of her parents; his second film, 2016’s I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, starred Ruth Wilson as a live-in aide who moves into the home of an author with dementia – searching for signs of who he was in the boxes he has left behind. And then there was last year’s sleeper hit Longlegs, his eerie Silence of the Lambs riff starring Nicolas Cage as a serial killer, in which a plucky FBI agent (Maika Monroe) discovers dark secrets in her family.

That path to understanding his father – and his mother for that matter – through film has brought Perkins to The Monkey. In cinemas this week, his new movie adapts Stephen King’s 1980 short story about two brothers (Perkins has a younger sibling, Elvis) and a cursed monkey toy, whose drum kit is a harbinger of death and misfortune, felling the people around them in wild and wacky ways. Bang! Explosion. Bang! Beheading. Bang! Stampede. The violent death of their mother is the final blow, estranging the boys for decades before the monkey’s return forces their reunion.

The story, however unlikely, struck a chord with Perkins. “Reading about these insane deaths, I was like, ‘Oh, I’ve had that happen to me a couple of times in my life’,” he says. “‘I’m an expert on this. I am an authority in losing people in insane ways’.” Nine years after the death of his famous father, his mother, the photographer and It-girl Berry Berenson, died on 11 September 2001, having been a passenger on American Airlines Flight 11 – the first of two planes to crash into the World Trade Center.

“Those sorts of deaths are hard to understand and you have to grapple with it, then you ask what’s the fallout? What does life look like afterwards? The story had meaning for me, and that’s always important because nothing is false at that point, everything becomes true.”

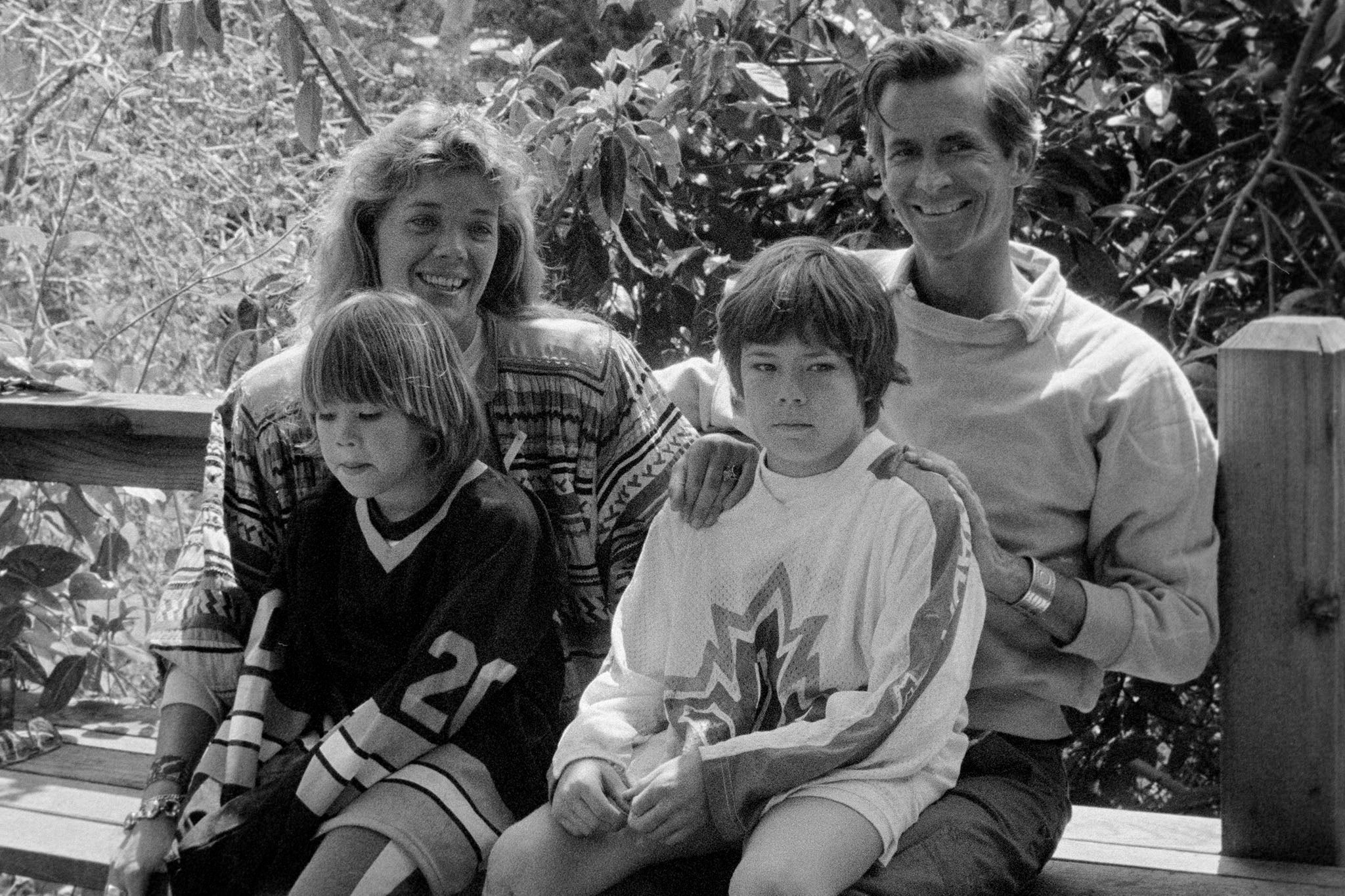

If Pretty Thing was focused on his father, Longlegs was about his mother and the stories that parents invent for the sake of their children. The fiction in question for Perkins was the narrative that cloaked his childhood, a fiction that left no room for his father’s homosexuality. (Anthony had been involved with men until undergoing conversion therapy; he had his first close relationship with a woman at 39, and married Berry at 41.)

Anthony and Berry maintained the public denials up until his death and, although their friends thought the marriage wouldn’t last, it ended up being an enduring stability for them both. Perkins maintains that despite it all, his parents loved one another. “My mom was a lot younger than my dad when they met and so he was already, you know, ‘Tony Perkins’ and she was this wide-eyed reporter,” he says. “She had a reverence for my dad and that remained the dynamic. They were good parental partners and they loved each other very much and all that, but I think my dad maintained this star-on-top-of-the-tree effect.”

Given his protagonists are often stand-ins for himself, it’s interesting that his stories tend to be female-driven, I suggest. Perkins thinks on it for a moment before answering. “The male mind tends to be more limited, whereas the beauty of a woman’s mind – and I don’t mean to generalise – tends to be more expansive, subtle, nuanced, instinctual,” he says. “And so grappling with the horror genre, which is about everything we can’t know, understand or verbalise, putting a woman in that just feels less limiting.” Does he think himself more aligned with that way of being? “I hope so.”

Perkins was 12 when he first appeared on screen in the somewhat forgotten Psycho II, featuring in flashbacks as a young version of his father’s soft-spoken psychopath. It’s a delicious bit of film trivia but, Perkins insists, that’s all it is. “I don’t think it was especially formative or seminal,” he says of the experience. To that end, he doesn’t recall much beyond a general feeling of fear. “I was convinced that I was in the place where it was set.” In reality, it was on a soundstage in Universal City in LA. “There were cameras all around and everything, but still I felt scared of the energy.”

In the decades that followed, Perkins acted here and there. He turned in small performances in films including Secretary and Not Another Teen Movie, as well as a more memorable one in Legally Blonde, as Dorky David Kidney – a buttoned-up mute unlucky in love. He says he gets recognised from that film upwards of five times a week. It’s the sort of thing you think might bug a guy like him. “No,” he insists. “People love it. No one comes up to me and is like, I hate that. It’s always [positive] so of course I’m happy to be associated with a movie that is, weirdly, a classic.”

Perkins never saw himself as an actor even then. “I don’t think I’m very good at it,” he demurs. “The real joy I get is empowering other people, and being a filmmaker is the more generous position for me anyway. It feels like you’re giving something and it’s worth something.” He does, however, briefly appear in The Monkey as a moustachioed swinger trampled to death in his sleeping bag by a pack of deer. Writing his own lines, Perkins says, tends to make acting more bearable.

One gets the sense Perkins would not suit the actor’s life, namely the fame of it all – apprehensive perhaps having seen his father’s experience of it as fickle and oppressive. In conversation, Perkins is to-the-point and gloriously un-media-trained – though when I bring up his recent remark calling Christopher Nolan films boring, he cringes: “S***, I really shouldn’t say things like that.” He is similarly outspoken on the idea of a director’s cut (“No”) and the subject of method acting (“I’ll call Jim Carrey Andy Kaufman if he needs me to – [but] he’s f***ing Jim Carrey”).

As for his father’s fame, Perkins says he took it as it came. “I never thought, ‘Oh gee, I really wish my dad was a dentist,” he shrugs. “I saw him as a beautiful sort of instrument. It was always impressive. I always felt special. And then as I get older and am making my own things, I’ll sit and watch Psycho and just be like, ‘Wow, that’s a really special thing. That’s a one-in-a-million movie performance’, and I feel a great deal of pride about it.”

That said, the success of Psycho had hardly guaranteed Anthony a lifetime of acclaim, and though he would go on to play many a moody, troubled man, he never again reached the heights of Norman Bates. By the time Perkins was a “sentient” teenager, he says, his father had reached “a weird downslope” in his career. “He was making bad movies because that’s what was available to him at the time,” Perkins says. “There was a weird dissonance between him being this cultural icon but doing these bad [films] and being sent to Budapest to make a movie before people were sent to Budapest to make movies.”

Beyond the jawline and the brows, Perkins thinks he and his father shared a similar sense of humour. The Monkey, for example, is first and foremost a comedy in the same vein as Gremlins. “I think one of the ‘gifts’ of experiencing tragedy early is that if you’re lucky to be able to process it and have support and a life afterwards – even if that life is hard for a long time – you can emerge with a distance and an appreciation of all aspects of living,” he says. “Being able to laugh at death is a real superpower, right? That’s probably what I’m trying to do most with this movie: to share the idea that death definitely sucks but, then, with some distance, you do heal.”

He pauses.

“Until the next time.”

‘The Monkey’ is in cinemas from 21 February