London’s population of 18th century dragons was tragically wiped out by a mini ice age – and a deadly volcanic eruption.

But now, thanks to new technology, the ‘descendants’ of the original winged monsters have finally come home – and the public will be able to get up close and personal with them.

In 1761, Scottish-Swedish architect William Chambers, who had seen dragon adorned pagodas in China, decided to build a similar one in Kew Gardens.

The famous pagoda is still there – but for the past 234 years it has been missing its dragons.

Originally there were 80 of them – all made of solid pine – but in the 1760s England was hit with winter temperatures so cold climatologists have labelled the period the “little ice age”.

In 1768, 1776, 1785, 1788 and 1795, the Thames froze over – and for most of those years, the ice was so thick Londoners held frost fairs on the river.

What’s more, in 1783 there was a huge volcanic eruption at Laki, in Iceland. Some 120 million tonnes of volcanic sulphur dioxide was blown south to Britain and continental Europe and an estimated 23,000 Britons died from inhaling the gas.

The volcanic pollution also caused extreme weather conditions – including huge storms and hailstones big enough to kill cattle.

It was this combination of extreme “little ice age” related cold, huge volcanic pollution driven storms and giant hailstones that appear to have ‘killed off’ the original Kew pagoda dragons.

Extreme freeze-thaw weathering and probable hailstone bombardment – and possibly additional damage from volcanic sulphuric acid – seems to have weakened the wooden dragons to such an extent that in 1784 they had begun to disintegrate, and had to be taken down, never to be seen again.

“The removal of the original Kew pagoda dragons occurred at a time of unusually severe climatic conditions, caused by the little ice age and by an Icelandic volcanic eruption – and we now believe that that unique combination of conditions would have played a significant role in the dragons’ deterioration, that led to their removal,” says Polly Putnam, a curator at Historic Royal Palaces, the charity which manages the pagoda.

Now, one of the world’s largest 3D printing companies – the US based 3D Systems – has used new technology at its High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire factory to restore the pagoda’s dragons.

However repopulating the structure with the winged monsters presented problems. The 10 roofs of the Kew pagoda are more than 250 years old, and apart from the lowest roof, would not have been able to bear the weight of normal ‘overfed’ dragons. As a result, 72 lightweight versions had to be created for the other nine roofs.

Each of the original wooden creatures weighed up to 250kg. Most of their modern, lightweight ‘descendants’ had to pass muster at just nine to 12 kilos each despite each being between 1.1 and 1.9m in length.

Although they look like the original, solid timber dragons, the new ornaments are hollow and made of nylon. What’s more, their toughened skins are just 4mm thick – including dragonesque green paint with red, blue and silver highlights and, in key places, a 0.0001mm thick layer of gold leaf to make them feel extra special on their historic roosts.

Whereas each of the 18th century dragons would have taken weeks to make, their modern nylon incarnations took, on average, just 80 hours. Each winged monster was 3D printed on the largest 3D printing machines of their type in the world.

“It’s been a daunting process – but a combination of painstakingly historical research and modern, cutting edge technology has made recreating our Kew dragons a huge success,” says Dr Lee Prosser, Historic Royal Palaces’ buildings curator.

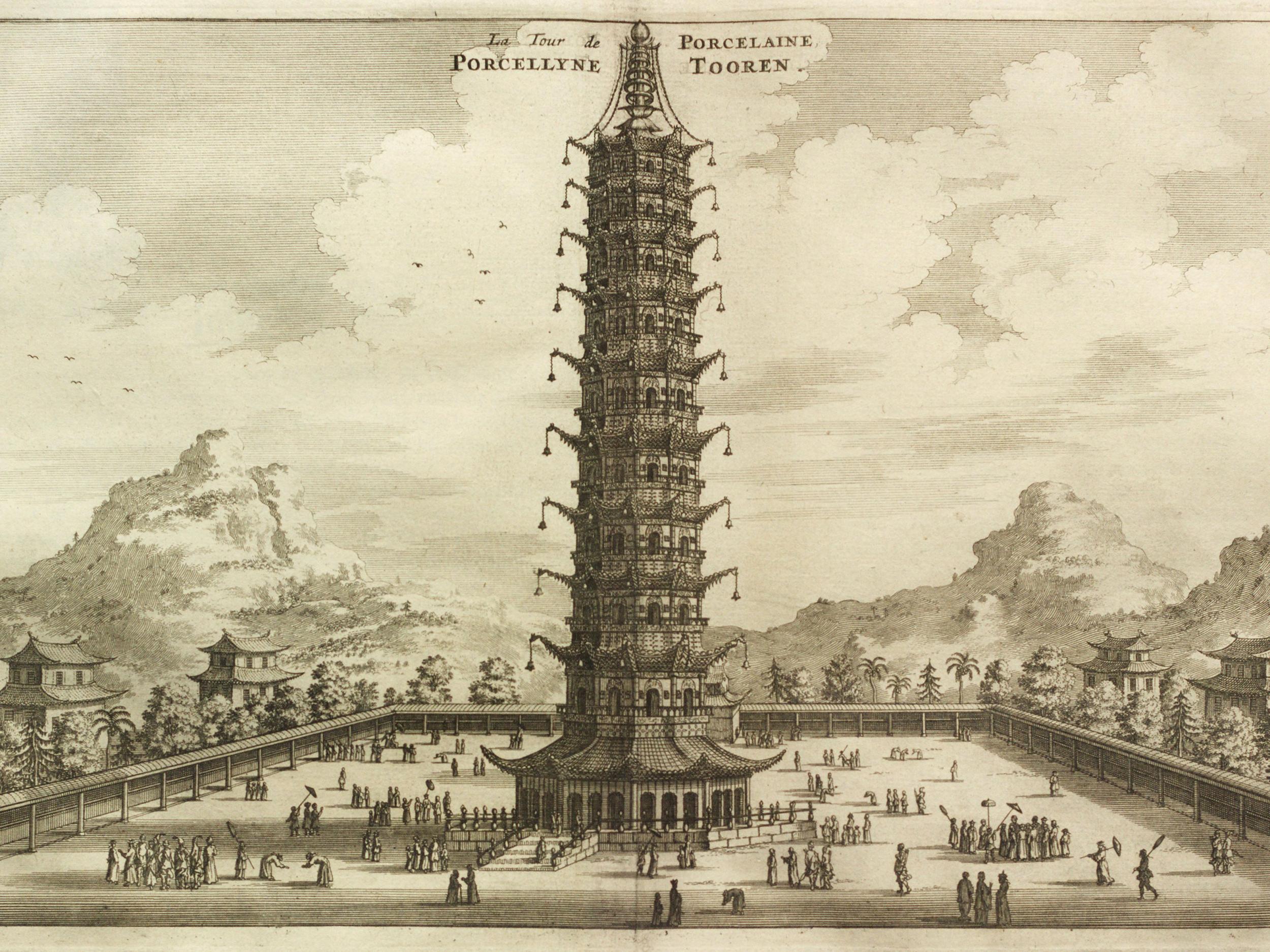

Detailed new research by Dr Prosser has concluded the Kew structure was based mainly on a very famous Chinese original – the Porcelain Pagoda.

Built in China’s early to mid 15th century imperial capital Nanjing in around 1430, the structure was destroyed in 1856 during a huge Chinese popular uprising, the Taiping Rebellion – history’s second most deadly conflict, after the Second World War.

Conservators have returned the Kew structure to its original Porcelain Pagoda like appearance by repainting it in its original 18th century colour scheme – lots of glossy green paint with a blood red top roof and green and white stripes on the undersides of the other nine roofs.

The pagoda will open to the public from 13 July.