In an occasional series, our authors make the case for or against controversial books.

In his afterword “On a Book Entitled Lolita”, Vladimir Nabokov never mentions the word paedophile. He never mentions the word rape either.

In his mind, Lolita is not about a man sexually and mentally abusing a 12-year-old girl. The novel is about him getting at America. Which is about as damning an assessment of a culture as you’re ever going to get.

Nabokov explains that having “invented” Europe and his native Russia in many critically acclaimed books, he turned an outsider’s eye on the Land of the Free. In effect – though he says he didn’t mean to – he ripped it to shreds.

Some might find Nabokov’s self assessment deliberately evasive. We sense in his elegant desperation the desire not to have his masterwork reduced to a scandalous headline – to “the psychological urges of a pervert” – and thus to the very thing that drove the masses toward it. This is a sleight of hand that today would be advised by a shiny PR team and a coterie of lawyers wringing their hands (but not written nearly as well).

When Nabokov was writing Lolita, he and his wife Vera were crisscrossing the United States butterfly hunting. The specimens they collected, pinned and captured under cut glass are preserved in museums all over the country like a trail of breadcrumbs.

Nabokov wants you to see the novel as he does: as points on a map, literal and figurative.

And when I thus think of Lolita, I seem always to pick out for special delectation such images as Mr Taxovich, or that class list of Ramsdale school, or Charlotte saying “waterproof”, or Lolita in slow motion advancing toward Humbert’s gifts, or the pictures decorating the stylised garret of Gaston Godin, or the Kasbeam barber (who cost me a month of work), or Lolita playing tennis, or the hospital at Elphinstone, or pale pregnant, beloved, irretrievable Dolly Schiller dying in Gray Star […] or the tinkling sound of the valley town coming up the mountain trail […] these are the nerves of the novel. These are the secret points, the subliminal coordinates by means of which the book is plotted.

His assessment rings true, though in my mind the sensations land differently. For Nabokov, the “hollows” and “byroads” of Lolita glow “like a pilot light somewhere in the basement”; the novel “throbs” in his “own private thermostat” as a constant comforting presence. For me, Lolita cracks open the mercury.

I have read Lolita every decade since I was a teenager. And in the roll call of memory the book unfurls in a cinematic wave: vivid, illicit, frightening. I too see Lolita advancing in slow motion toward Humbert’s gifts – and a shiver of recognition runs through me.

As a teenager, I wanted to be Lolita – just as so many good girls in the West in the late 20th century were effectively trained to do. I coveted the false power of the ingenue in secret. I imagined myself in the car with Humbert in the dead of night on those long empty highways, as he drives Lolita away from safety to those functional motels – the “clean, neat, safe nooks” where “they could make it up gently”.

Humbert’s male gaze is like a living thing, visible, hanging like a seductive shroud over everything, a terrible forcefield capable of creating a ruinous edge of competition and jealousy between mother and daughter and drawing Lolita closer and closer to him.

In my twenties, I wanted to save Lolita because, as Humbert observes, she has “nowhere else to go”.

In my thirties, I wanted to be Nabokov instead. The recognition of what he was able to conjure on the page ignited a wholly different sense of shock and awe.

In my forties, my only aim was not to get too political about it.

The problem with censorship

Reconsidering Lolita in the 21st century raises interesting questions about the relation of literature to censorship, book banning, and the contemporary equivalent of expressive erasure, cancel culture.

The manuscript of Lolita was initially rejected by every American publisher who considered it. It was eventually published in France in 1955 by the notoriously fearless Maurice Girodias, who also published English language versions of books censored in Britain and America, including works by Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Samuel Beckett and William Burroughs, among others.

After its publication, Lolita was not officially banned by the US government, but it was banned by various local jurisdictions, schools and outlets. It was also banned as obscene for periods of time in France, England, New Zealand, Canada, Argentina and South Africa. In Australia – recognised by many literary researchers as one of the harshest regulators in the world – readers were denied access until 1965.

These bans were designed to protect morality and uphold national order. Researcher Nicole Moore suggests that, in the new millennium,

The idea of there being a nation state that can draw a border around itself to say, “we are like this, our reading public is like this, and different to this other reading public”, that is just a notion that has gone with the wind.

Not so. Nation states don’t censor as much as they used to, if at all, but the machinations of censorship continue in arbitrary ways. In April 2022, PEN America released an Index of School Book Bans – the first time the organisation has conducted a formal count of this kind. It was compiled as a response to “rapidly expanding scope of censorship over the last ten months”, during which 98% of titles were deemed to have been banned in certain jurisdictions without due process (though what that process might be, exactly, remains unclear).

Lolita features on the list only once. According to today’s arbiters of morality, the most dangerous books in American schools are not Lolita or the Marquis de Sade’s Justine or Pauline Réage’s Story of O. In fact, risqué literary classics feature only rarely.

The index reads instead like a sad denial of contemporary adolescent identity, particularly in relation to race and sexuality. The majority are Young Adult titles which position LGBTQIA+ and multicultural characters front and centre.

George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, a book of essays about growing up Black and queer, is banned in over 29 jurisdictions. Gender Queer, a graphic memoir written and illustrated by Maia Kobabe and celebrated for its coming of age exploration of non-binary identity, is banned in over 40 – from New York to Florida, Washington, Virginia and Texas.

This deliberate erasure of queer voices and stories highlights the problem with censorship of any kind. Which books get to go through to the keeper cannot depend on who is drawing the lines in the sand, yet this is ultimately how all censorship works.

If the power to ban an artwork on ideological grounds exists, then the capacity to do so cannot be limited. We cannot decry the banning of books in one arena yet cancel them in another – this is intellectually confused. No less importantly, the impulse to suppress challenging or disturbing art transfers the burden of reality onto the art rather than onto ourselves.

The afterlife of Lolita

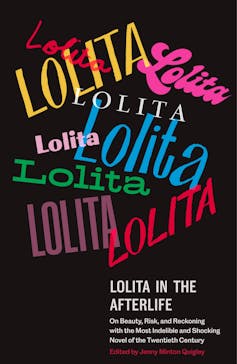

In 2021, Jenny Minton Quigley, the daughter of Walter J. Minton, who first published Lolita in America in 1958, edited a collection of essays titled Lolita in the Afterlife. A fierce advocate of unfiltered artistic expression, just as her father had been, Quigley grew up in “the house that Lolita built”. She wanted to test the enduring power of Lolita in the glare of the #MeToo movement and the fraught political climate of Trump’s America.

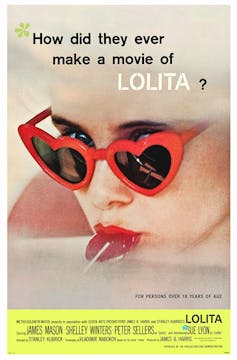

In Lolita in the Afterlife, Nabokov is critiqued and celebrated. The writers pick apart Lolita’s rendering in film, her appropriation by the fashion industry as a “paean to white femininity”, the limits and capacity of the empathetic imagination, and the ugly beauty of Nabokov’s prose. Roxane Gay describes him as a “tricky bastard”.

The volume also considers the experiences of reading Lolita in trigger-happy colleges, in the oppressive gloom of lockdown, and in Iraq, where “pleasure marriages” between men and girls as young as nine are still culturally sanctioned.

But it is the final essay, “I Cannot Get Out Said the Starling” by Mary Gaitskill, that best captures the distinction between reading a work of art and holding the work or the writer responsible for the real trespasses operating outside of its imaginative orbit.

Moral outrage over a book is a convenient deflection and does nothing to stem the tide of abhorrent behaviours. In fact, it fuels appetite for the works in question. Lolita has sold over 50 million copies worldwide.

Gaitskill gets this. Like Nabokov, she is a writer unafraid to commit to the page what others dare not say. In her short story collection Bad Behaviour, she digs around remorselessly in the grey areas of human psyche and interaction. She turns a nonjudgmental eye on Lolita:

Truly, the darkness – the cruelty – of the story is not obscured but heightened by the beauty of the language through the force of artistic contrast, and that contrast is stunning, making the reader feel the wild, often terrible incongruity of human life on earth. This incongruity – the natural coexistence of beauty and destruction, goodness and predatory devouring, cruelty and tenderness, a world in which countless torturer’s horses scratch their “innocent behinds on countless trees” – is a core mystery of life. And that mystery is the true heart of Lolita.

What emerges in Lolita in the Afterlife is a recognition that outrage misdirected at the book or the writer does nothing to negate the realities aligned to it.

Despite all the noise and the banning, Nabokov’s novel still stands. It stands next to pornographic spin-offs and Lolita lollipops and the seemingly endless commodification and exploitation of young girls and women. It stands in the middle of a global rise in human sex trafficking in the 21st century, with American men as the biggest consumers.

It stands alongside alarmingly high rates of the abuse of children. A Child Maltreatment Study recently released by the Queensland University of Technology suggests that 65% of Australians have experienced some form of abuse as minors. The monster is still in the room.

Almost 70 years since it was first published, Lolita continues to be read from Tokyo to Tibet to Tehran. Because it needs to be. Because books like Lolita are a reckoning. For Nabokov, Lolita wasn’t the butterfly – she was the pin.

Sally Breen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.