As Pan Am Flight 103 Maid of the Seas cruised at an altitude of 31,000ft none of the 243 passengers and 16 crew were aware of the Samsonite suitcase in the hold.

None of them knew about the Semtex concealed in the Toshiba radio cassette player inside the suitcase.

Thirty-eight minutes after the Boeing 747 left Heathrow, as it was about to start crossing the Atlantic en route for New York, the bomb exploded.

At 7.03pm on 21 December 1988, as the small town of Lockerbie in southern Scotland prepared for Christmas, it began raining wreckage and bodies.

Everyone on the plane died. So did 11 people on the ground. The death toll of 270 made it the deadliest terrorist attack ever to hit the UK.

Thirty years ago on Friday the name Lockerbie became synonymous with disaster.

The grim sequel is that today, Lockerbie does not just conjure up images of tragedy.

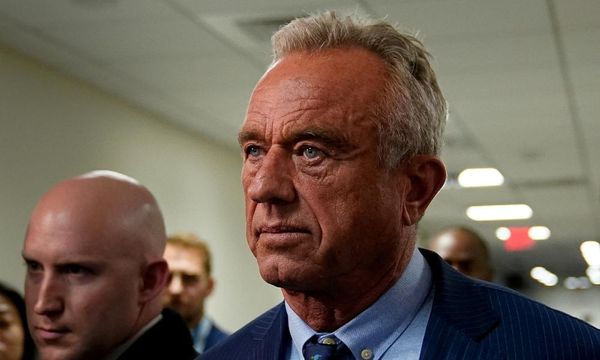

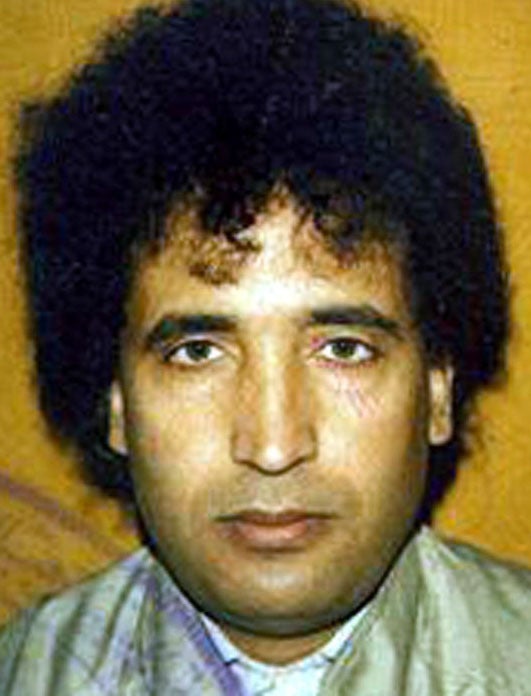

It brings to mind suggestions of conspiracy, of murky deals done in the diplomatic margins, of international machinations that betrayed justice, ensuring – some say – that the only person convicted in connection with the bombing, Libyan Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, was an innocent man.

About the only certainty is the horror.

The explosion caused the plane to shatter into thousands of pieces that landed in an area covering about 850 square miles (2,200 square km).

Scattered among the molten metal and burning fuel were the bodies. One teenager from a farming family, checking their fields with his dad, found three corpses, among them a seemingly untouched baby with “amazing blond hair”.

A mountain rescue team leader described seeing “Hell on Earth”.

A fuel-laden wing had landed on Sherwood Crescent, exploding in a blast so fierce that cast-iron fences streets away melted into puddles, leaving a 26ft (8m)-deep crater where 11 houses had been.

Fourteen-year-old Steven Flannigan had just popped out from his home in the crescent to go and see a friend who would check that his sister’s Christmas present of a new bicycle was working properly.

He never saw his sister or his parents alive again.

Steven’s big brother David, 19, who had been due to come home for a family reunion on Boxing Day, instead returned to Lockerbie to survey the wreckage.

“He stumbled to the crater that had been his home,” a friend told The Guardian. “He returned carrying this tiny, plastic watering can, the sort of thing you might buy for 50 pence at Woolworths. All fluorescent pinks and greens, completely untouched. He bought it in and put it down carefully next to his chair. Then he said ‘That's all that I can find of my family’”.

After turning to drugs and drink, David died of heart failure in a cheap hostel in Thailand on 29 December 1993, eight days after the fifth anniversary of Lockerbie.

Steven became known as “the orphan of Lockerbie”. When he died after an accident on a railway line in August 2000, he was described as the tragedy’s last fatality.

Far away from Lockerbie, in the English Cotswolds, Dr Jim Swire was at home with his wife Jane. They knew their 23-year-old daughter Flora, a neurology PhD student, had booked a last-minute flight to spend Christmas in the US with her boyfriend.

Jim was in the study when Jane called to him: “You must come and watch the Nine O’Clock News because there’s been this plane that’s gone down.”

Jim had to identify his daughter from the mole on her toe.

Grief turned this Eton and Cambridge-educated doctor into a tireless campaigner.

Then 52, he became arguably the face of those grieving for the 43 Britons killed in the atrocity. (Lockerbie claimed the lives of people from 21 different nations, including 190 Americans.)

Dr Swire lobbied constantly, appealing to the United Nations, exposing the continuing gaps in airport security by smuggling a case of marzipan, which has the same density and appearance as Semtex, onto a transatlantic flight.

He was, as Jane told The Independent, “like a dog on a hunt [having] to chase every hare until he gets a narrative that makes sense.”

It still took nearly 12 years before the trial of two Libyan suspects began on May 3 2000, at a specially convened tribunal, operating under Scottish law and heard by three Scottish judges without a jury, at Camp Zeist, the Netherlands.

The tortuous road to trial included the imposition of sanctions on Colonel Gaddafi’s Libya, suggestions the international consensus on sanctions was collapsing, and lengthy secret negotiations between the UK, US and the Netherlands, initiated by Tony Blair’s foreign secretary Robin Cook.

The investigation that put Megrahi and alleged accomplice Lamin Khalifa Fhimah in the frame had involved interviewing 15,000 people and examining 180,000 pieces of evidence.

When the trial began in the Netherlands, Dr Swire was convinced both men were guilty.

By the time the judges acquitted Fhimah and found Megrahi guilty on 31 January 2001, Dr Swire was convinced that the only man convicted was innocent.

He befriended Megrahi, visiting him, exchanging Christmas cards, becoming relentless in his efforts to clear the Libyan’s name, and thus to find his daughter’s ‘real killers’.

He had sat through the whole trial, seen for himself some of its more puzzling incidents.

Dr Swire had registered the bewilderment of Pierre Salinger, former chief foreign correspondent for America’s ABC network, when the judges thanked him for his evidence and asked him to leave the witness box.

"That's all?” asked Salinger, who had interviewed the two suspects. “Wait a minute. You're not letting me tell the truth. I know who did it. I know how it was done."

Lord Sutherland, one of the judges coolly informed him: "If you wish to make a point you may do so elsewhere, but I'm afraid you may not do so in this court."

The Scottish Crown Office - backed it should be said by many American victims' families - remains sure Megrahi was a Libyan agent, a key player in a plot where an unwitting Air Malta worker checked the Samsonite onto a Frankfurt-bound flight as a favour for a “friend” in Germany, where the suitcase was routed to Heathrow, then loaded on to Pan Am 103.

Tony Gauci, whose shop Mary’s House was near Malta’s airport, identified Megrahi as the man who bought clothes from him that were later found to have been packed into the Samsonite, concealing the bomb.

But there were reports of large undisclosed payments going from the US Justice Department to Mr Gauci.

The suspicion was growing that, either by accident or cover-up, Megrahi had become the innocent fall guy who got a life sentence for mass murder.

The Libyan was described, by The Independent among others, as less secret agent and more “Tripoli airport control manager briefly assigned to Libyan intelligence for bureaucratic rather than specialist tradecraft reasons.”

Many came to believe the Lockerbie atrocity was the work of Palestinian militants, with suspicion falling in particular on the Palestinian Popular Struggle Front (PPSF) and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC).

The trial, for example, had heard evidence from FBI agent Edward Marshman that Jordanian bomb maker Marwan Khreesat told him he had supplied the PFLP-GC with explosive devices similar to the one used to down Pan Am 103.

By contrast there was considerable scepticism about the prosecution’s attempts to link Libya’s intelligence services to the improvised explosive device that destroyed the jet.

A fingernail-sized fragment of circuit board found in the wreckage was identified by prosecutors as being part of a timer made by contractor Thuring and sold by Swiss company Mebo to the Libyan armed forces.

But sceptics said independent analysis of the timer fragment showed it had a pure tin coating, whereas Thuring devices were covered in a tin-lead alloy.

Dr Swire came to disbelieve the official story of a bomb going from Malta to Frankfurt to London, thinking instead that the bomb had been smuggled through Heathrow and only ever travelled on one aeroplane: Pan Am 103.

One Heathrow staff member reportedly told police in January 1989 that he had seen a hard-shell Samsonite in a luggage container heading for the Boeing 747’s hold before the Frankfurt feeder flight that was supposed to have carried the bomb had even landed at the London airport.

Some accounts were prepared to accept that Libyan money might have helped fund the Palestinian militants – the US bombing raid on Tripoli in 1986 certainly gave Gaddafi plenty of motive for becoming (or continuing as) a terrorist paymaster.

But the downing of Iran Air Flight 655 by a missile fired in error from a US warship in July 1988 gave another Middle East government a far more recent grievance, one that would have made targeting American civilian air passengers particularly appealing.

Whatever the truth, the conflicting accounts and the seeming entanglement with Middle Eastern intrigue left many with the sense that Lockerbie had become a decidedly murky affair.

And then, in 2009, things acquired a whole new layer of murkiness. Megrahi was released from Greenock prison on compassionate grounds and allowed to return home to Libya.

As the release was sanctioned by Kenny MacAskill, justice secretary in the SNP administration in Edinburgh, officials let it be known that Megrahi was dying from cancer and had only about three months to live.

Rather awkwardly for the UK and Scottish administrations, he lived for nearly three more years, dying in Tripoli in May 2012 aged 60.

Both the Westminster and Edinburgh governments insisted the release decision had been based purely on the interests of justice, with international power politics having nothing to do with it.

But this was happening in the honeymoon period after Tony Blair’s 2004 ‘Deal in the Desert’, sealed with a handshake in Gaddafi’s tent, helping to end sanctions against Libya, while delivering billion-dollar contracts for Western oil companies.

A US Senators’ report would later suggest that oil giant BP had lobbied for a prisoner transfer agreement between the UK and Libya.

Both the oil company and the British government denied that the discussions had specifically mentioned Megrahi. At the time of his release, however, one Whitehall source had told The Independent: “It was clear this case is very, very important to the Libyans.”

And then the honeymoon with Gaddafi was ended by the Libyan revolution of 2011. He went back to being a pariah, the UK joined a bombing campaign against him, and the rebels finished him off after dragging him from a drainage pipe near Sirte.

And if anything, the intrigue around Lockerbie deepened.

Why, for example, was Colonel Gaddafi’s former spy chief Moussa Koussa, who fled to London during the revolution, allowed to fly on to Qatar after just three days?

Andrew MacKinlay, a former Labour MP and member of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee, remembered meeting Mr Koussa in Tripoli in 2005 and being told by a British diplomat: “This man is up to his neck in Lockerbie”.

Mr Koussa remains safely ensconced in Qatar, although he was eventually asked to leave his luxury suite in the Doha Four Seasons.

In 2015 Scottish prosecutors effectively re-opened the Lockerbie investigation by naming two Libyans they wanted to talk to: Abdullah al-Senussi, Gaddaffi’s brother-in-law and formerly a senior Libyan intelligence official, and Abu Agila Masud, a man believed to have bomb-making skills.

Both men are in jail in Libya. Scottish and American prosecutors are said to be hopeful they will be allowed, despite the chaos now bedevilling Libya, to talk to the two suspects.

A report in this week’s Times suggested prosecutors were “closing in” on their two targets. The response from the Libyan government – or at least the UN-backed version of it – was said to have been “positive and constructive”.

Megrahi’s family, meanwhile, has launched a fresh appeal against his conviction to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC).

When he died in 2012, his brother Abdulhakim said: “Just because Abdulbaset is dead doesn’t mean the past is now erased. We will always tell the world my brother was innocent.”

For his part, Dr Swire described the death of his friend as “a very sad event”. He praised the way that Megrahi, even when dying and in great pain, had sought to pass on the information amassed by his defence team.

Dr Swire himself is now 82.

Thirty years on from being called from his study to watch a TV news bulletin that changed his life, he is still searching for simple, undisputed truth about what happened to his daughter and 269 others.

Given what we now know about Lockerbie, it seems rash to assume that anyone will ever find it.