It’s common to hear about large amounts of plastic waste floating around our oceans. But while the problem of plastic waste is growing globally, in Australia it’s going the other way.

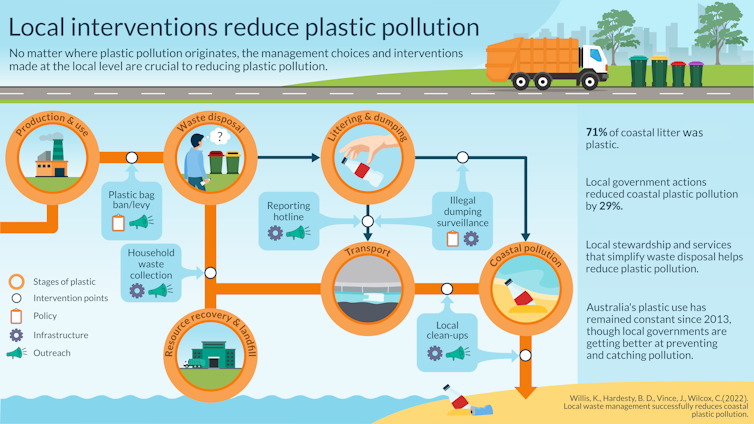

This is because most plastic rubbish we find on Australia’s beaches comes from us, not from other countries. Our new study shows local efforts in waste management have worked, reducing coastal litter by 29% over the last six years.

We found the greatest reductions in litter in the environment when it was simpler to access bins or when people were motivated through economic measures. In essence, these actions either save time or money for people trying to dispose of waste appropriately.

What doesn’t work? Awareness raising without tools or infrastructure to back it up. Messages and reminders don’t work if there are no options at hand.

Global issue, local solutions

Plastic pollution is a global crisis harming wildlife, economies and livelihoods. The recent signing of the Global Plastics Treaty has added momentum to the world’s efforts to cut the estimated 6-12 million tonnes of plastic waste entering our oceans every year.

But we still know little about practical ways of cutting the amount of plastic entering the environment outside of rhetorical campaigns to ban plastic.

To find out what works, we focused on local governments. Councils are well placed to tackle the problem, as they are typically at the coal face of waste management. Councils collect and dispose of our waste while also dealing with illegal dumping and litter.

Read more: We analysed data from 29,798 clean-ups around the world to uncover some of the worst litter hotspots

We undertook 563 litter surveys across 183 beaches in 32 local governments. From this, we identified actions with the largest effect on reducing coastal litter. Then we used three established theories of human behaviour to try to understand what makes these local actions successful.

In short, we found the most successful actions either saved time or money for people and local governments trying to dispose of waste in the right way.

We found that, in isolation, efforts to control plastic waste by targeting personal and social norms in the community did not reduce plastic litter on local beaches. This suggests a narrow focus on raising awareness will not work. But when awareness efforts are combined with tools and infrastructure, they become more effective.

Directly involving community members in clean-up activities like Clean Up Australia Day, or programs focusing on dumping and littering also helped keep our coastlines cleaner. Such programs encouraged people to watch for and report litterbug behaviour through hotlines.

Changing how we think of plastic

To keep reducing waste around Australia, we need to transform our relationship with plastic. If we stop viewing plastic as a disposable commodity and start recognising its value, it will become something too good to throw away.

One of the biggest positive local government changes we saw was the shift towards collecting different streams of household waste and recycling. Local governments and the public are moving away from a collect and dump mindset to a reduce, sort and improve approach.

Many Australian households now have three or four bins to separate glass, green waste (often with food scraps) and paper from their general waste and mixed recycling. These bins not only make it easier for us to separate and discard our waste properly, but well-separated waste and recycling streams make it easier for local governments to produce revenue from rubbish.

Read more: Four bins might help, but to solve our waste crisis we need a strong market for recycled products

With Australia’s recent ban on waste exports, better waste management holds clear benefits for people, communities, businesses and the environment.

Tackling litter-prone areas

Although litter is now declining along our beaches, we still have a long way to go. We’ve found high levels of plastic near our major cities and along remote coastlines, such as the west coast of Tasmania and the Gulf of Carpentaria. Pollution in remote areas is largely due to lost and discarded fishing gear washed up in remote areas.

By contrast, we can do a lot more to tackle hotspots closer to home, such as waterways and bushland near major population centres.

In Australia, we find more litter in socially and economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods as well as along our highways and in car parks and retail strips. By contrast, we find less in areas we associate with higher aesthetic and cultural values such as beaches and parks.

Interestingly, economically disadvantaged areas seem to benefit the most from container deposit schemes and other economic incentives. These incentives appear to shift the behaviour of litterers and create an incentive to collect containers left in the environment.

It is encouraging to know we are the main source of plastic on our beaches. We have the power to change what happens locally. We don’t have to wait for global-scale action on plastics.

On this front, Australia has changed quickly and for the better. Our local governments and environmental groups can guide us to make wise decisions on waste.

Kathryn Willis was supported by the School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania

Britta Denise Hardesty receives funding from United Nations Environment, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Oak Family Foundation.

Chris Wilcox receives funding from Ocean Conservancy, PADI Aware, and CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere. He also receives funding from Oak Family Foundation and PM Angell Foundation.

Joanna Vince receives funding from the CSIRO for plastics related work.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.