In March 1841, William Henry Harrison became the ninth president of the United States. He gave the longest inaugural speech in history—one hour and 45 minutes—developed a cold, and then, after a mere 32 days in charge, succumbed to a mixture of pneumonia and 19th-century medicine.

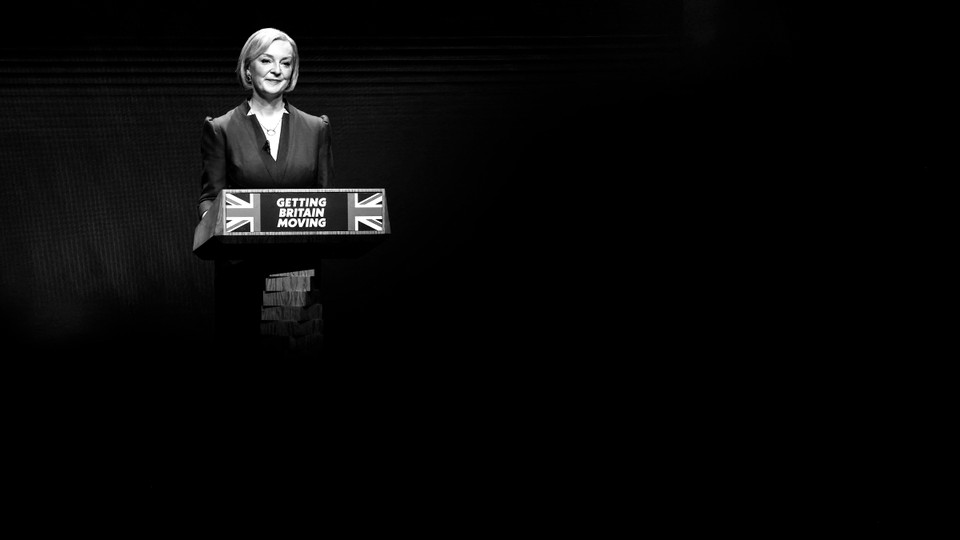

According to a persistent, if apocryphal, rumor, Harrison caught that fatal chill at his inauguration. Here in Britain, Liz Truss’s prime ministership was dealt a similarly mortal blow by her own government’s first set-piece event—the launch of an economic plan designed to turn Britain into a low-tax libertarian paradise. Just six weeks into her tenure, her ambitions have shuffled off this mortal coil, rung down the curtain, and joined the choir invisible. They are deceased. They have ceased to be. Truss ran for prime minister on a promise to unleash growth. Instead, she unleashed market turmoil, a fall in the pound, and a precipitous drop in her party’s poll numbers. Even now, she says she wants to lead her party into the next election, as if she had not just immolated her credibility; her longstanding ideological commitment to Britannia Unchained has proved entirely resistant to facts and changing circumstances.

[Read: The Liz Truss travesty becomes Britain’s humiliation]

On September 23, Truss looked on as Kwasi Kwarteng—her chancellor of the Exchequer, political soulmate, and personal friend—put forward a “mini budget” that would cut taxes on top earners, remove a cap on bankers’ bonuses, and cancel a planned corporate-tax hike. This was the “biggest package in generations,” he said. Dust off the Laffer curve, silence the “doomsters” worried about where the money would come from, and luxuriate in what even a sympathetic commentator described as a “Reaganite show of fiscal incontinence and Thatcherite derring-do.”

The left-wing opposition hated it—tax cuts for millionaires as Middle Britain struggled with high energy bills, rampant inflation, and rising mortgage costs—but so did the financial markets. Government bonds fell sharply, which left pension funds struggling to stay solvent. Five days later, the Bank of England was forced to step in and stabilize the British economy. A right-wing chancellor had implemented right-wing economic dogma, and the free market swooned—in horror.

At the start of the month, as Truss’s Conservative Party gathered for its annual conference, pressure from her own colleagues led the prime minister to junk her most toxic policy, the tax cut for the rich. She papered over the humiliation with a tone-deaf speech attacking anyone who criticized her as part of the “anti-growth coalition.” These people, she claimed, “prefer talking on Twitter to taking tough decisions … From broadcast to podcast, they peddle the same old answers. It’s always more taxes, more regulation, and more meddling.”

But even this gratuitous dollop of culture-war blather couldn’t restore calm to the markets or the restive ruling party. Everyone could see that Truss and Kwarteng’s authority was shot to pieces. The Economist pointed out that, once the official mourning period for Elizabeth II was taken into account, Truss “had seven days in control. That is roughly the shelf-life of a lettuce.” A tabloid newspaper promptly set up a livestream of a decaying vegetable, to see which lasted longer. The lettuce now looks sad and wilted. So does the prime minister.

[Helen Lewis: Boris Johnson’s terrible parting gift]

Desperate to remain in power, Truss fired Kwarteng on Friday—even though she had signed off on his disastrous proposals. Yesterday, Kwarteng’s replacement, Jeremy Hunt, went on television and unloaded clip after clip into Truss’s cherished economic policies. In three days (his time in the job) and five and a half minutes (the length of his televised statement), Hunt unwound the entire basis of Truss’s leadership so comprehensively that the past month might as well have never happened. It was a bloodbath: “The most important objective for our country right now is stability,” he said, reversing almost all the tax cuts announced in the mini budget. (The subsidy for domestic energy bills was also drastically reduced in scope: This distinctly big-state policy, forced on the government by high wholesale gas prices, was—and still is—extremely costly, and a more cautious leader might have restrained their other plans as a result. Not Liz Truss, though, who had pledged to “hit the ground running.”)

The speed and savagery of Truss’s collapse has been astonishing—particularly because her predecessor, Boris Johnson, won a general election with an impressive majority of 80 seats just three years ago. Back then, the Conservatives looked like an all-conquering horde, even after a decade in power and the protracted agony of the Brexit negotiations.

So what’s gone wrong? Everything. Since taking office, she has made a series of bad calls. She appointed a cabinet of fellow hard-liners, rather than drawing on the breadth of her party. She fired the most senior civil servant at the treasury, because he was too fond of fiscal orthodoxy. She dismissed the strategist who masterminded the 2019 election victory. Her chief of staff has spent his entire tenure embroiled in scandal after it was revealed he was being paid by his old lobbying firm, rather than taking a government salary. She didn’t prepare the country for the top-rate tax cut. Apparently, she was sure that the right-wing media’s adoration would be enough to convince the rest of Britain that millionaires were the group that most needed a break right now.

Even worse, all the way through, Truss has been barely visible, as if her actions speak for themselves. Which, sadly, they have. In the past few days, the Conservatives’ deteriorating polls have indicated that they would not simply lose the next election; they would no longer be the second largest party in Parliament. Unless their fortunes undergo a complete reversal, the Conservatives—who have dominated the postwar period and consider themselves the “natural party of government” in Britain—would suffer a wipeout on the scale of the Canadian center-right in 1993.

Under these circumstances, possible successors have begun to present themselves. Hunt, the new chancellor, has unsuccessfully run twice for the leadership and would love another chance. Penny Mordaunt, whom Truss defeated over the summer, denied yesterday that the prime minister was hiding “under a desk” instead of facing the House of Commons. In doing so, Mordaunt accidentally-on-purpose repeated the accusation. (The headlines and push alerts wrote themselves.) Rishi Sunak, another defeated rival, is also circling—ready to point out that his unheeded warnings about Truss’s economic policies have proved to be prescient. Boris Johnson’s allies are even suggesting that Britain take him back, Berlusconi-style, for another try.

[Read: ‘We’re not going to make that mistake again’]

Earlier this year, I wrote that Truss was walking into an economic hurricane. For some reason, she decided the best response to this was to toss fistfuls of cash into the air in the form of unfunded tax cuts. She has failed because she won the leadership by telling her party’s most ardent activists what they wanted to hear. She has failed because she is a born-again Brexiteer, and had already swallowed the lie that reality can be bent to ideology. She has failed because, in a prime-ministerial system, leaders can be expected to implement even their most irresponsible promises—so the link between action and consequence is brutally obvious.

Liz Truss has been cosplaying as Margaret Thatcher without noticing that the Britain of 2022 looks nothing like the Britain of 1979, in either its demographics or its economic problems. Her time as prime minister is a parable of being careful what you wish for: True Trussonomics—Brexit-loving, libertarian, trickle-down—has certainly been tried. Unfortunately, it went about as well as William Henry Harrison’s inaugural address.