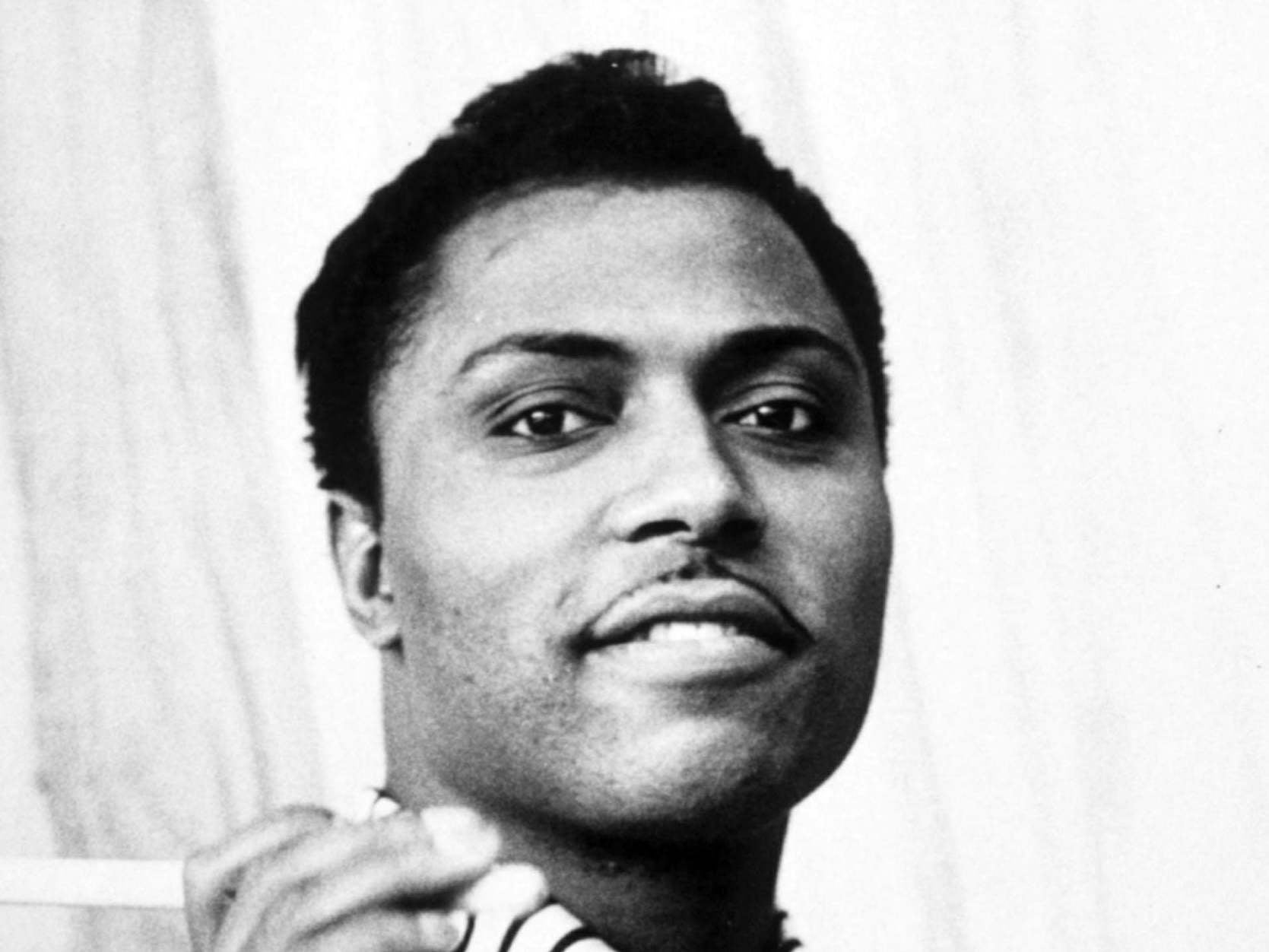

Keith Richards encapsulated the impact that Little Richard had on British society when he said of the American rock’n’roller’s 1955 hit “Tutti Frutti”: “It was as if, in an instant,” the Rolling Stones guitarist said, “the world changed from monochrome to technicolour.”

In Liverpool, teenagers John Lennon and Paul McCartney were listening and watching: Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” was the first song McCartney sang in public. In Hibbing, Minnesota, one Robert Zimmerman, soon to become Bob Dylan, declared in the high-school yearbook for 1959: “Ambition: To join Little Richard.” Otis Redding, growing up in Little Richard’s home city of Macon, Georgia, was besotted by his music and modelled his vocal style on him.

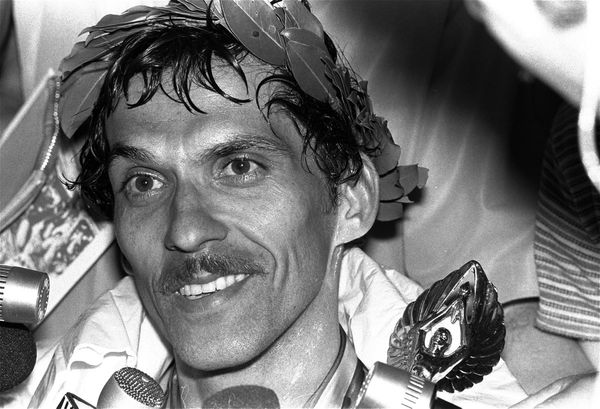

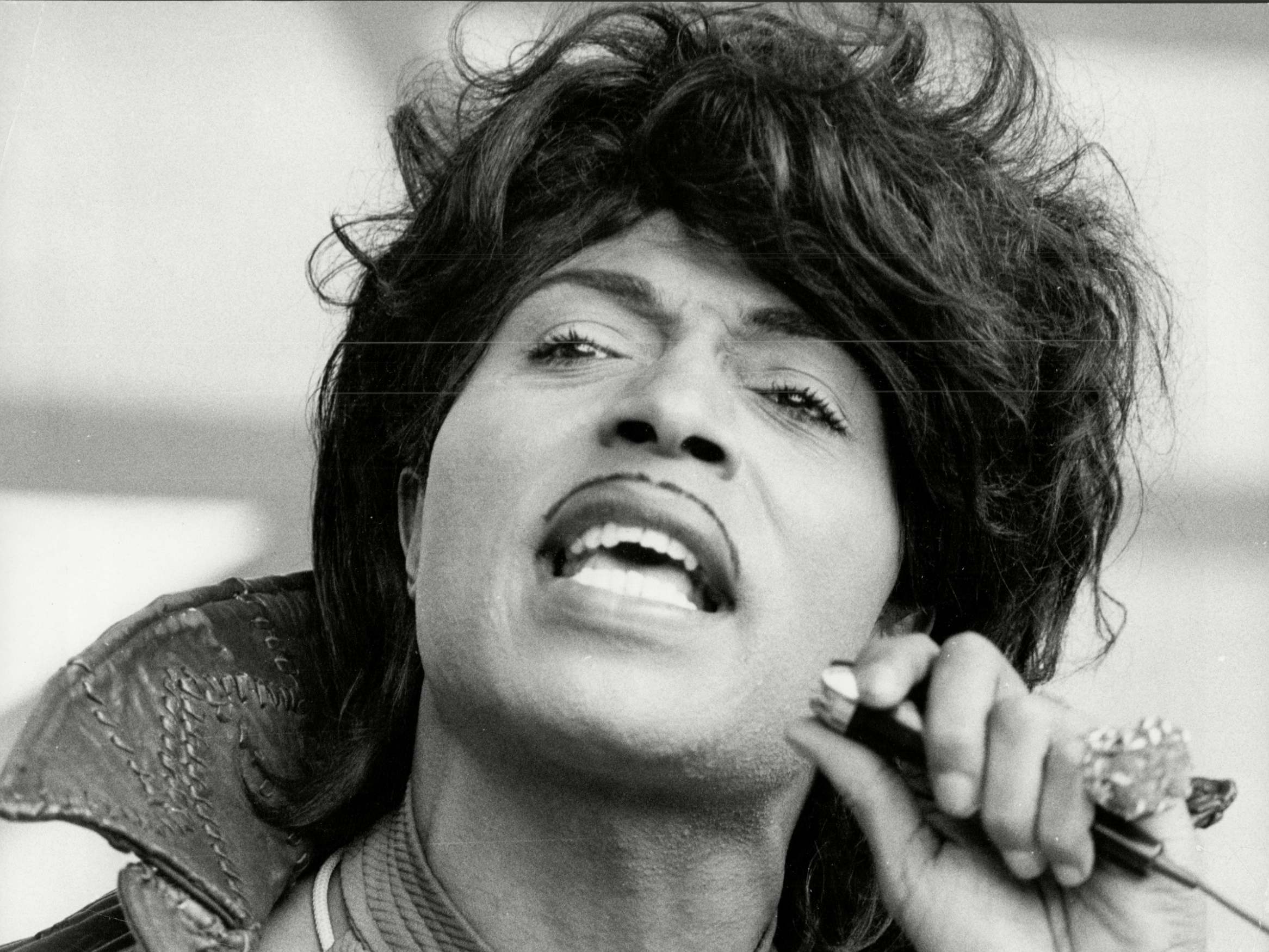

Richard, who has died aged 87, regularly lit up the singles charts on both sides of the Atlantic. During the period from the mid-Fifties until the emergence of the all-conquering Beatles, he took to the stage wearing capes, blouses and sequin-studded suits in vivid, clashing hues and exotic materials. His trousers were tight, he wore make-up and his hair was groomed into an extraordinary construct, as much as six inches high.

Invariably he clambered on top of his piano, soaked in sweat and whipping audiences into a frenzy with a repertoire that included future rock staples such as “Long Tall Sally”, ”Rip It Up”, “Good Golly Miss Molly” and “Lucille”.

But the story of Little Richard was no straightforward narrative in which a larger-than-life entertainer rode the initial wave of enthusiasm for rock’n’roll, fell from favour, resurfaced and was thereafter made a nice living playing revivalist package tours. He was a troubled soul, torn throughout his life between the Christian doctrine inculcated in him by his father, a church deacon, and his popularity as one of the pioneers in a genre that he himself branded “the devil’s music” and “demonic”.

He was bisexual, which conflicted with his religious faith, not only plunging him into periods of guilty introspection and short-lived promises to “get right with God” but also landing him in jail. His father was alarmed when he performed in drag and banished him from the family home at 16.

Richard Wayne Penniman was the third eldest of 12 children born to Bud and Leva Mae Penniman. His mother wanted to christen him Ricardo but a misunderstanding led to the birth certificate recording his name as Richard. From an early age he sang gospel music in church, where his impassioned, shouting, almost screaming style earned the nickname “War Hawk”.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a nationally known artist who brought a rock sensibility to spiritual music by accompanying herself on electric guitar, heard him sing when she came to play in Macon. She invited the 14-year-old to join her on stage for two songs.

The positive reception he received attracted the attention of band leaders. He knew only one secular number, Louis Jordan’s “Caldonia”, but his rendition impressed Buster Brown’s Orchestra sufficiently for them to take him on the chitlin’ circuit (chitterlings were a soul food item made from pig’s intestines). They played to black audiences in the racially segregated south of the United States. Already known to his family as Lil’ Richard because of a slender, diminutive physique, the 18-year-old was renamed Little Richard by his touring colleagues.

His early, blues-flavoured records, for RCA Victor in 1951, failed to sell beyond the Macon area. A deal with Peacock Records kept his recording career alive, although by 1953 he was working as a dishwasher by day and fronting a band, The Tempo Toppers, at night. At the suggestion of Lloyd Price (whose 1952 million-seller “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” provided an obvious template for “Good Golly Miss Molly”), he sent an audition tape to the Specialty label, who bought out his Peacock contract.

His new producer, Bumps Blackwell, viewed him as Specialty’s answer to Ray Charles; Little Richard saw himself in the Fats Domino mould. The company duly hooked him up with two of Domino’s trusted band, Early Palmer (drums) and Lee Allen (sax), but still the magic, and the sales, eluded him. Then one day, between recording sessions, the four of them adjourned to a bar where Little Richard began playing a risqué number that he had performed in the clubs.

The song was “Tutti Frutti”. Blackwell recognised its potential but feared the lyric’s ribald sexual innuendo would prevent radio play. Dorothy LaBostrie, a lyricist, was hired to clean it up, reputedly rewriting the song in 15 minutes. The record began with a memorable piece of nonsense vocalising by Richard, who yelled, in a supposed parody of a drum intro: “A wop bop a loo mop, a lop bam boom.”

Recorded in three takes in September 1955, by November it had shot to No 2 in the US Rhythm & Blues chart, No 17 nationally and No 29 in the UK. Mojo, the British magazine, named it No 1 in its chart of Records That Changed the World and Rolling Stone listed at No 43 in the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

The floodgates were open; the hits poured through. Early in 1956 came “Long Tall Sally”, a top 10 success in the US and UK (where The Beatles used it as the title track on a 1964 EP). Before the year was out, “Rip It Up”, “Slippin’ and Slidin’”, “Ready Teddy” and “The Girl Can’t Help It” had all charted.

Suddenly he was in demand for tours, attracting both black and white fans at a time of widespread segregation. He was also coveted by movie-makers as Hollywood tried to tap into the youth market. As well as The Girl Can’t Help It, which also featured Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent and Fats Domino, he appeared in Don’t Knock the Rock and Mister Rock and Roll.

In late 1957 the first of his periodic crises of conscience engulfed him. Playing in a Sydney stadium, he saw a fireball flash across the sky. He saw it as a sign from the Almighty, explaining many years later: “I got up from the piano and said: ‘This is it. I’m through with showbusiness. I’m going back to God.”

The “sign” was, in fact, a Soviet sputnik. Yet he left the tour, losing fees and provoking lawsuits, before returning to enrol at a college in Alabama to study theology. He formed the Little Richard Evangelical Team, preaching across America, and when he resumed recording, it was to make gospel records. Quincy Jones, who worked on his King of the Gospel Singers LP, once said Richard was better in the studio than any artist with whom he had worked.

In 1959 he married Ernestine Campbell. After adopting a one-year-old, Danny Jones, who later worked for Richard as a bodyguard, they divorced within four years.

By that time he had decided to re-enter the pop world, which had been transformed by his fans The Beatles. “Bama Lama Bama Loo” restored him to the British top 20 in 1964. A Granada TV special, The Little Richard Spectacular, was a ratings success. And the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame recently estimated he had sold 32 million records by 1968.

But the decade was marked by conflicts, internal and external. Some clergymen in the American south deemed him too secular and persuaded God-fearing radio DJs to shun his records; and he felt producers wanted to shoehorn him into the Motown mould.

The Seventies, when David Bowie and others dabbled with Little Richard’s androgynous look, produced similar fluctuations. His part in the documentary film Let the Good Times Roll was acclaimed, and he filled a side of the soundtrack double album. He also played on sessions with Canned Heat, Delaney & Bonnie, Joe Walsh and Bachman-Turner Overdrive.

However, he struggled against cocaine and heroin addiction. In 1973 – when two 1967 cuts, “Get Down With It” and “I Don’t Want To Discuss It”, were spreading his name within Britain’s Northern Soul subculture – he again renounced secular music. He resumed his gospel career, which, if nothing else, gave the lie to the notion that he was a one-trick pony.

It was the mid-Eighties before Little Richard finally accepted that serving God and rocking the joint need not be mutually exclusive, though he remained confused about how to reconcile his sexuality with his faith. “I would get up of an orgy and go pick up my Bible,” he told biographer Charles Wright. He described himself then as “omnisexual”, but in 1984 he called homosexuality “unnatural”. It was not until 1995 that he told an interviewer he was gay.

He continued performing into the Nineties, recording with The Beach Boys, Elton John and Bon Jovi before duetting with Jerry Lee Lewis on a cover of The Beatles’ “I Saw Her Standing There” for the latter’s 2006 album Last Man Standing.

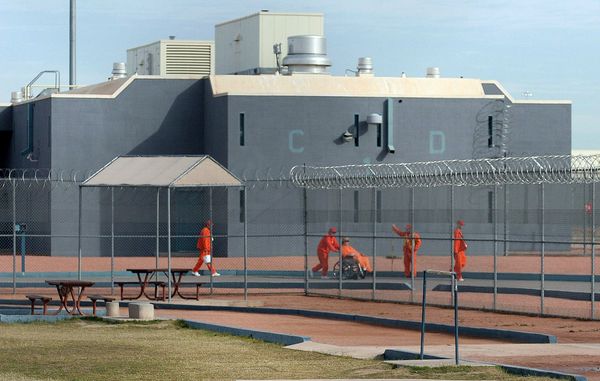

Richard was confined to a wheelchair after hip-surgery in 2009 left him in constant pain and he suffered a heart attack in 2013.

He is survived by his son Danny.

Richard Penniman (Little Richard), singer, songwriter, musician and preacher, born 5 December 1932, died 9 May 2020