This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Maureen Cohen is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Venus Global Climate Modelling at The Open University.

Do aliens sleep? You may take sleep for granted, but research suggests many planets that could evolve life don't have a day and night cycle. It's hard to imagine, but there are organisms living in Earth's lightless habitats, deep underground or at the bottom of the sea, that give us an idea what alien life without a circadian rhythm may be like.

There are billions of potentially habitable planets in our galaxy. How do we arrive at this number? The Milky Way has between 100 billion and 400 billion stars.

Seventy percent of these are tiny, cool red dwarfs, also known as M-dwarfs. A detailed exoplanet survey published in 2013 estimated that 41% of M-dwarf stars have a planet orbiting in their "Goldilocks" zone, the distance at which the planet has the right temperature to support liquid water.

These planets only have the potential to host liquid water, though. We don’t yet know if any of them actually do have water, much less life. Still, that comes to 28.7 billion planets in the Goldilocks zones of M-dwarfs alone. This is not even considering other types of stars like our own yellow sun.

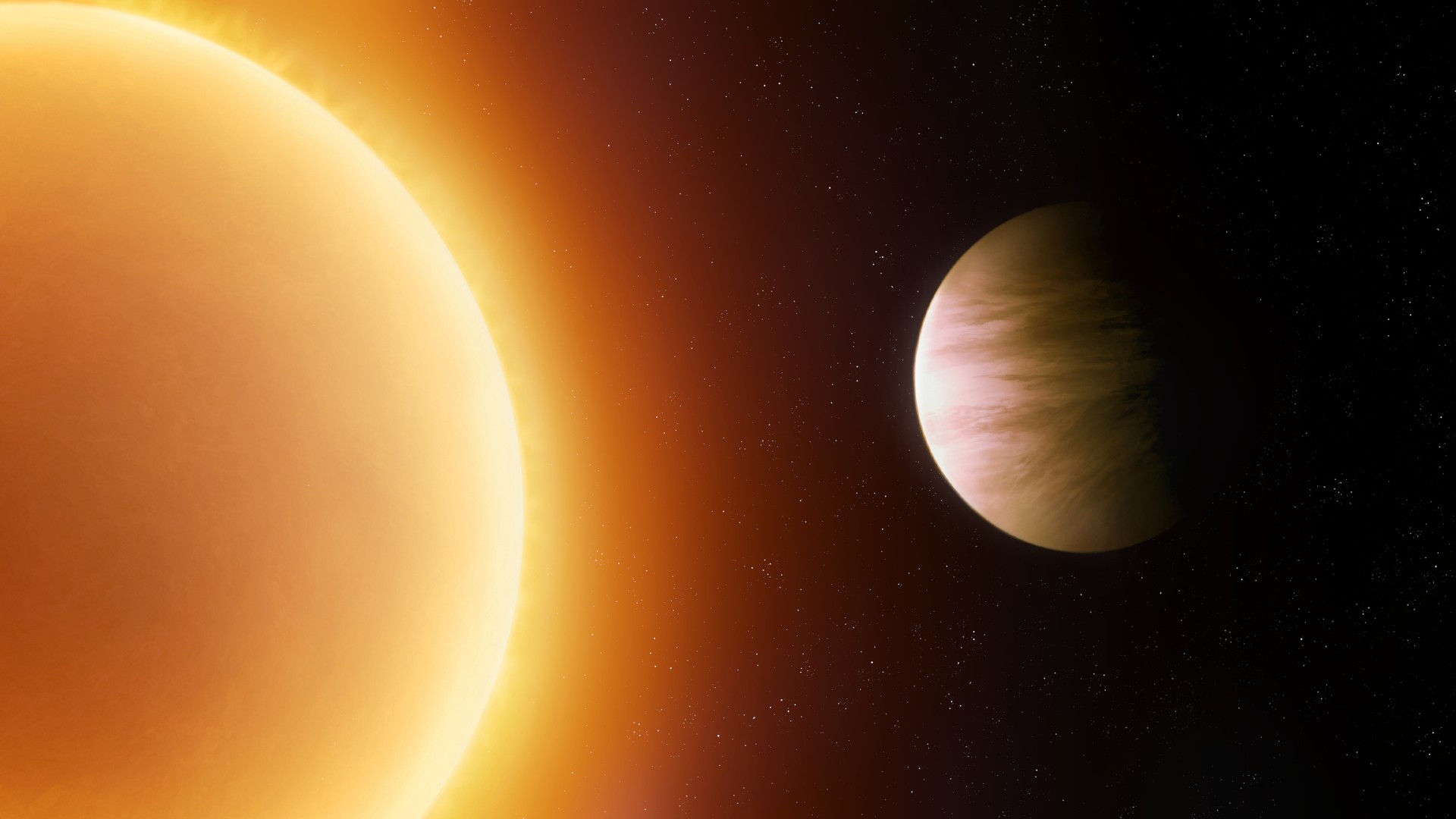

Rocky planets orbiting in an M-dwarf's habitable zone are called M-Earths. M-Earths differ from our Earth in fundamental ways. For one thing, because M-dwarf stars are much cooler than the sun, they are close-in, which makes the gravitational pull of the star on the planet immensely strong.

The star's gravity pulls harder on the near side of the planet than the far side, creating friction that resists and slows the planet's spin over aeons until spin and orbit are synchronized. This means most M-Earths are probably tidally locked, which is when one hemisphere always faces the sun while the other always faces away.

A tidally locked planet's year is the same length as its day. The moon is tidally locked to the Earth, which is why we always see only one face of the moon and never its far side.

A tidally locked planet may seem exotic, but most potentially habitable planets are probably like this. Our closest planetary neighbor, Proxima Centauri b (located in the Alpha Centauri system four light-years away), is probably a tidally locked M-Earth.

Unlike our Earth, then, M-Earths have no days, no nights and no seasons. But life on Earth, from bacteria to humans, has circadian rhythms tuned to the day-night cycle.

Sleep is only the most obvious of these. The circadian cycle affects biochemistry, body temperature, cell regeneration, behavior and much more. For example, people who receive vaccinations in the morning develop more antibodies than those who receive them in the afternoon because the immune system's responsiveness varies throughout the day.

We don't know for sure how important periods of inactivity and regeneration are to life. Maybe beings that evolved without cyclical time can just keep on chugging, never needing to rest.

To inform our speculation, we can look at organisms on Earth that thrive far from daylight, such as cave-dwellers, deep-sea life and microorganisms in dark environments like the Earth's crust and the human body.

Many of these life-forms do have biorhythms, synchronized to stimuli other than light. Naked mole rats spend their entire lives underground, never seeing the sun, but they have circadian clocks attuned to daily and seasonal cycles of temperature and rainfall. Deep-sea mussels and hot vent shrimp synchronize with the ocean tides.

Bacteria living in the human gut synchronize with melatonin fluctuations in their host. Melatonin is a hormone your body produces in response to darkness.

Temperature variations caused by thermal vents, humidity fluctuations, and changes in environmental chemistry or currents can all trigger bio-oscillations in organisms. This hints that biorhythms have intrinsic benefits.

Recent research shows M-Earths could have cycles that replace days and seasons. To study questions like these, scientists have adapted climate models to simulate what the environment on an M-Earth would look like, including our neighbor Proxima Centauri b.

In these simulations, the contrast between dayside and nightside seems to generate rapid jets of wind and atmospheric waves like those that cause Earth's jet stream to bend and meander. If the planet has water, the dayside probably forms thick clouds full of lightning.

Interactions between winds, atmospheric waves and clouds may shift the climate between different states, causing regular cycles in temperature, humidity and rainfall. The lengths of these cycles will vary by planet from tens to hundreds of Earth days, but they won't be related to its rotation period. While the star remains fixed in the sky of these planets, the environment will be changing.

Perhaps life on M-Earths would evolve biorhythms synchronized to these cycles. If a circadian clock organizes internal biochemical oscillations, it may have to.

Or perhaps evolution would find a weirder solution. We could imagine species that live on the planet's dayside and migrate to the nightside to rest and regenerate. A circadian clock in space instead of in time.

This thought should remind us that, if life exists out there, it will upend assumptions we didn't know we had. The only certainty is that it will surprise us.