Last month the mayors of Queensland’s two biggest cities proposed a referendum on reintroducing daylight saving in the Sunshine State.

South Australians, meanwhile, have recently heard calls for popular votes on retail trading hours and recreational cannabis.

In our system, politicians pass laws and make decisions, but sometimes they first gauge public opinion by holding an advisory policy referendum or “plebiscite”. Most people think of these as rare events. The 2017 same-sex marriage survey was just the fourth national policy referendum in more than a century, compared to over 40 referendums on constitutional amendments.

But new research shows policy referendums have been far more frequent at the state and territory level. This rich and largely forgotten history fills out our understanding of Australian democracy. It also demonstrates the enduring appeal of giving the public a direct say on contentious issues.

Read more: Explainer: the same-sex marriage plebiscite

Alcohol, daylight saving and other controversies

Australia’s states and two mainland territories have together held 56 referendums since 1901. About a dozen of these have put forward proposals for constitutional amendment. The remainder have concerned policy questions.

New South Wales has made most use of the referendum, having put 16 proposals, followed by Western Australia with 12. The Northern Territory’s 1998 poll on statehood remains its only one. Victoria has been least enthusiastic in recent times – its last referendum, on hotel closing hours, was in 1956.

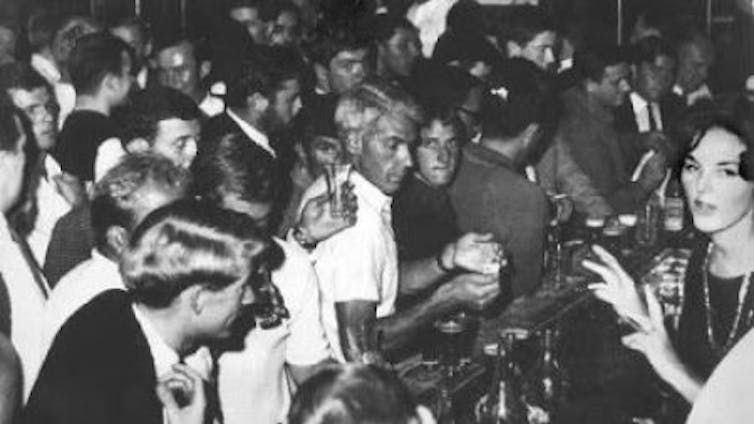

About a third of all state and territory referendums have been about alcohol policy. The topic of hotel closing hours appeared frequently on ballot papers in the early 20th century. During the first world war, voters in three states backed 6pm closing at licensed premises. This choice proved consequential, giving rise to the infamous “six o’clock swill”.

Some governments have asked voters about prohibition. In 1928, residents of the Federal Capital Territory (now the ACT) were asked if they wanted to allow the private sale of alcohol. The territory had been “dry” since its creation in 1911, prompting many to dash across the border to Queanbeyan to quench their thirst.

On polling day, a majority of electors voted to end prohibition. The timing could not have been better for the nation’s federal politicians, who just a year earlier had begun sitting in Canberra.

In more recent times, daylight saving has been put to voters more than any other issue. By the 1970s, many states had experience with daylight saving but the question was whether people wanted to keep it. Around 70% of electors voted ‘Yes’ to this in New South Wales (1976) and South Australia (1982).

Public support was never tested in Victoria and Tasmania. These states opted to keep daylight saving without holding a referendum.

But daylight saving has proved hugely divisive elsewhere. A 1992 Queensland referendum revealed a stark urban-rural divide on the issue. More than 60% of residents in the south-east of the state voted “Yes”, but opposition in regional and rural areas was enough to defeat it.

On the other side of the continent, Western Australian governments have asked voters about daylight saving four times, most recently in 2009. On each occasion the answer has been a decisive “No”.

State and territory electors have also voted on the teaching of scripture in schools, the location of a hydro-electricity dam on Tasmania’s Gordon River, and self-government for the ACT. More often than not, these polls have attracted significant media attention and been fiercely contested.

High success rate

In Australia, a lot of commentary on federal referendums is about how difficult it is to pass them. Voter have approved just eight of 44 proposals (or 18%) for constitutional amendment. This has led some commentators to say Australians are naturally inclined to vote “No”.

The history of state and territory referendums challenges this notion. Referendums held by state and territory governments enjoy a much higher success rate.

Of the 41 state/territory referendums that have asked voters a Yes/No question, 19 (or 46%) have been carried. The success rate varies across policy and constitutional polls. About a third of policy referendums have passed, while voters have approved an impressive three-quarters of constitutional proposals.

The reasons for the different federal and state/territory success rates are complex and remain to be fully explored. But the sub-national referendum record bucks the conventional wisdom, showing that Australians are indeed willing to vote “Yes”.

This is worth keeping in mind as we consider the prospects of future federal referendums, including a possible vote on a First Nations Voice.

Read more: Is Australia ready for another republic referendum? These consensus models could work

When should we hold policy referendums?

Given Australia’s long track record of using policy referendums, should we be holding more of them?

Australians are generally in favour of the idea. In research conducted for the Australian Constitutional Values Survey (ACVS) in 2017, my colleagues and I found more than 80% of respondents gave “in principle” support for direct democracy.

And referendums, when run well, can strengthen our democracy. They can provide opportunities for public deliberation on tough issues, give people a sense of contribution, and build trust and engagement.

But referendums are not suitable for all issues. The question is where we should draw the line. Four years after the marriage survey, this is a big philosophical question that remains unresolved.

Governments have held advisory polls on alcohol, daylight saving and same-sex marriage, so why not also on COVID rules, the date of Australia Day or – as Pauline Hanson has proposed – on immigration levels?

The case for a policy referendum is arguably stronger when the proposal concerns basic governing arrangements – think statehood or some electoral laws – or contentious social issues. It will be weaker when the proposal is highly technical or could endanger minority rights.

The ACVS suggests people’s attitudes towards direct democracy align with this approach to some degree. Respondents favoured a popular vote on some social issues (such as voluntary euthanasia) but preferred to leave more technical matters (such as emissions targets) to parliament.

We might also reason that policy referendums are best reserved for those issues that genuinely divide the parliament, or the parties, to the point of stalemate. This was arguably the case with same-sex marriage.

Basic principles are helpful, but it is not possible to be definitive about the circumstances in which policy referendums should or should not be held. It will always be a case-by-case judgment.

With that in mind, we could do more to promote debate about when policy referendums should be held. Currently the decision rests entirely with politicians, who tend to favour them only in narrow circumstances.

Parliaments in all jurisdictions could establish processes for individuals and groups to propose referendums on certain issues. Special committees could be tasked with considering these proposals and reporting back. A more radical idea would be to enable citizens to directly initiate referendums by gathering a certain number of signatures from voters.

In any event, there is scope for us to think more creatively about how we integrate policy referendums into our representative politics. And, as the state and territory record shows, this would build on a rich democratic practice that stretches back more than a century.

Paul Kildea has previously received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.