The dull glint of the bomblets winked on the tarmac of a car park in Ukraine’s strategic port city of Mykolaiv.

Just moments earlier, a suspected cluster munitions attack had hit the busy residential area – tearing apart several cars. It left a deadly trail of remnants, and worried residents had called in assistance from people more experienced to dispose of the submunitions.

Dima, a veteran seaman who previously served in eastern Ukraine and had planned to sign up to fight in this war, was one of those asked to help.

Bent over a clutch of bomblets, the 41-year-old made a split-second judgement about whether any of them were still live and could be safely picked up.

It was the wrong decision.

One of the submunitions exploded in his left hand, blowing it to pieces. It chewed up both of his thighs and ripped open his chest.

“I found a group by a wrecked car, and I thought they were all spent. I was wrong,” he tells The Independent three days later, still hooked up to a spider web of machines in the critical care unit of one of Mykolaiv’s hospitals. Despite being very ill, he insists he wants to speak.

Medics asked that the hospital not be identified, as it was one of the last remaining medical centres in the city not hit by Russian strikes and they feared it might become a target.

“Some had already exploded, there were ones that hadn’t been activated yet, so soldiers were shooting them at a safe distance,” Dima adds, his face pale yellow, his voice weak.

“I found a group by a wrecked car, and I thought they were safe. Big mistake.”

Cluster munitions are banned by 110 countries worldwide including the UK because they are inherently indiscriminate and therefore a violation of international law. They release dozens if not hundreds of bomblets – carpeting an area that can cover a football pitch – and shred flesh, metal, and even walls.

We don’t know if Dima will be able to walk again

Many of them do not explode on impact, effectively becoming deadly landmines that litter and menace civilian neighbourhoods for weeks if not years thereafter.

Even those experienced in identifying the submunitions, such as Dima, can get it wrong.

The head of the hospital’s ICU – who asked to only be identified as Dr Dymtro – showed The Independent a photo taken of Dima immediately after the explosion. His legs, in Dr Dymtro’s words, “are like mince”, while his intestines and liver were also damaged.

“He lost most of his left hand, his upper legs were shredded like meat,” the ICU chief says as he walks around a ward packed with civilians being treated for multiple injuries from cluster munitions. One of the attacks hit a busy shopping district just a day earlier on 4 April.

“We don’t know if he will be able to walk again, he needs new skin for his leg and months of treatment that we just don’t have here now,” Dr Dymtro adds.

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), both Russia and Ukraine have stockpiled the Smerch and Uragan artillery rockets equipped with cluster munition warheads, and neither country has signed the international treaty banning the use of them.

The group also says that since Vladimir Putin launched his invasion on 24 February, Russia has repeatedly dropped them on Mykolaiv, a strategic port city and gateway to Ukraine’s Black Sea coast.

Richard Weir, a member of HRW’s crisis and conflict team that investigated two strikes in the city, says their use in populated areas is “abhorrent and unlawful”.

“These submunitions are often designed to spread fragments over a wide area to kill and injure as many people as possible,” he says. “Those responsible for these attacks should be held to account.”

The Independent has shown photos of recent strike sites, including the 4 April attack, to an expert who – speaking on condition of anonymity due to the nature of their work – said that they are consistent with the fragmentation patterns of a cluster strike.

In two other hospitals, two different doctors said the injuries they had treated were also consistent with cluster munitions. One woman who was caught up in the attack on the shopping district had to have small pieces of shrapnel removed from her skull.

A team from medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) visited Mykolaiv on 4 April and said they witnessed shelling during a hospital visit. After the strikes, the MSF team said it saw numerous small holes in the ground scattered over a large area that “could be consistent with the use of cluster bombs”.

Ukrainian officials say the attacks over the last few weeks have increased as Mr Putin has withdrawn his troops from the Kyiv and neighbouring northern regions, only to reposition them ready to focus his fury on consolidating more ground in the east and the south.

They are lashing out because they are losing

Gaining control of Mykolaiv, a city that local officials say is responsible for a quarter of Ukraine’s grain export cargo, would not only strangle the country’s economy but offer a strategic jumping off point for Russia to attack neighbouring Odesa, Ukraine’s largest port, a key supply line, and the “pearl” of the Black Sea coast.

Moscow came close to overrunning Mykolaiv earlier in the war but was pushed back to neighbouring Kherson, which it currently occupies. Battles are ongoing and fierce. Since Russian forces were forced to retreat from the outskirts of the city last month, their bombardment of the centre of Mykolaiv has increased, according to local authorities,

On 29 March, a cruise missile hit the city’s main government building, gouging an enormous hole through its side and killing at least 36 people as well as injuring dozens of others.

On the afternoon of 4 April – the day before The Independent visited Mykolaiv – a suspected cluster munition attack hit a packed shopping district in the city centre, killing 10 people and injuring more than 60 others. Footage of the attack showed bloodied bodies slumped over a bus stop and lying on the steps of shops.

Another suspected cluster munition attack took place just two days earlier near a supermarket. There was also a missile attack on the city’s Hospital No 5, which The Independent visited. Astonishingly, no one was killed. A pregnant woman who had been evacuated to the basement mid-attack gave birth in the makeshift bomb shelter.

“Since the beginning they have been shelling us almost every day but recently they have stepped it up with attacks twice a day, often using cluster munitions,” says Mykolaiv’s mayor, Oleksandr Senkevech. Thousands of buildings in the city have been hit, including orphanages, kindergartens, schools, and nearly every hospital, he says.

“My opinion is they want us to be scared and to give up, and that they are trying to prepare another ground operation which hasn’t had any success so far,” Senkevech adds.

“They are lashing out because they are losing.”

Mykolaiv has borne the brunt of Russian forces eyeing up Odesa, where officials and citizens acknowledge their neighbouring city has acted like a kind of military and human shield for them.

And so now it is a city on edge. Even when quiet, there is a fear that cluster munitions could land at any moment, and at any location. The residents of Mykolaiv, numb after so much bloodshed, try to continue their normal life each day – not knowing if it might be their last.

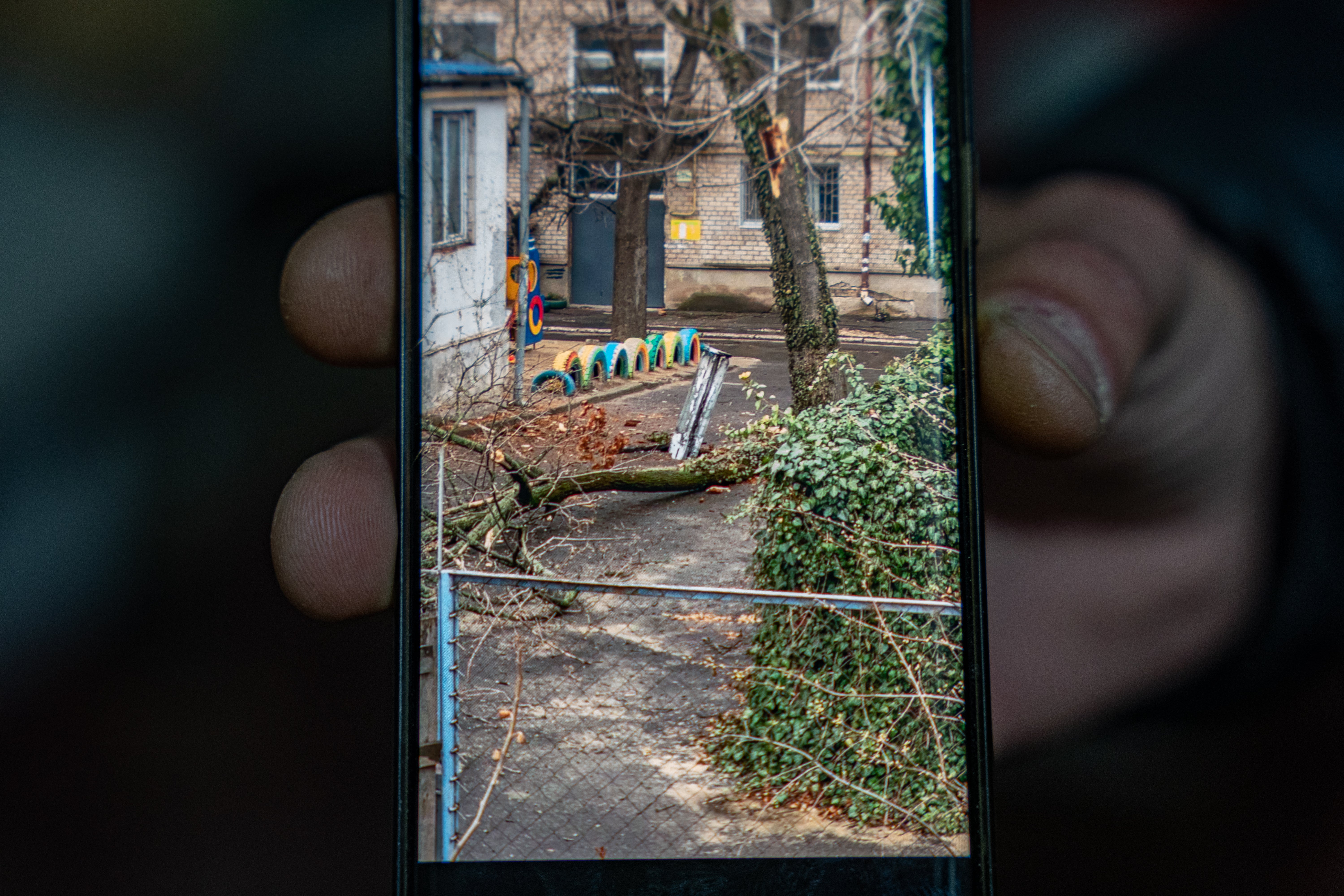

In the basement of a random residential building where people have gathered during one of the regular air raid sirens, Alexi, a computer programmer, shows a photo of an unexploded rocket which landed in the playground next to his home a few days ago.

The Independent showed the image to a weapons expert who said it appeared to be the cargo section of a Smerch rocket that carries the internationally outlawed bomblets.

It is wedged into the ground next to a multicoloured swing and seesaw.

Alexi says he was almost killed by another rocket on a separate occasion. “It landed right next to me, the only reason I’m still here is because it didn’t explode,” the 33-year-old says, visibly shaken, as two children clutch their pet puppy and play games on their mobile phones in the darkness.

“Several friends were wounded by shrapnel wounds from cluster munitions, the situation is getting worse and worse every day. “

“But we do not want to leave – this is our home,” Alexi adds.

That sentiment is shared by a group of young volunteers who, despite the daily threat of shelling and missiles, are busy coordinating supplies for civilians and soldiers in the city.

Anya, who before the war worked at a factory making clothes, coats and shoes, decided just after the invasion to start collecting supplies of food and medicine for those living in the hardest-hit areas.

The 33-year-old says they then started to receive requests for body armour and blankets from soldiers and members of the territorial defence as the fighting intensified and the lingering winter cold set in.

Using her contacts at the factory, she started making bulletproof vests and military sleeping bags after downloading templates from the internet.

The vests’ steel plates, which the army has tested, are made from melted down truck springs.

With a 70-person strong team of volunteers, they have made more than 1,000 of the vests and more than 300 sleeping bags since the start of the war.

“We are almost constantly hit and so someone had to do something,” she says from their hub. “I can’t carry a weapon so this is my way to help.”

Back at the hospital, Dr Dymtro does another round of the ICU, checking on the patients whose bodies are mangled by shrapnel. A patient who was injured at the start of the war moans in pain behind him.

Despite the possibility that he might be permanently injured, Dima says he still wants to sign up to the military as he had planned to do.

“I will do everything I can to recover so I can fight. The injury has only strengthened my resolve,” he adds, wincing as he speaks.

“They think they can scare us into giving up. But we won’t.”