On June 28, 1969, the genteel town of Bath staged a small concert that helped change the world: The Bath Festival Of Blues, hosted at the Bath Pavilion Recreation Ground.

Promoters Freddy and Wendy Bannister were a husband and wife team who had been putting on gigs at the Bath Pavilion – up-and-comers like The Beatles or Jimi Hendrix – were asked if they would put on a show “for the kids” on the recreational ground opposite the Pavilion in the centre of town. The Bath Festival Society had been accused of being elitist and wanted to give this new so-called ‘rock music’ a try.

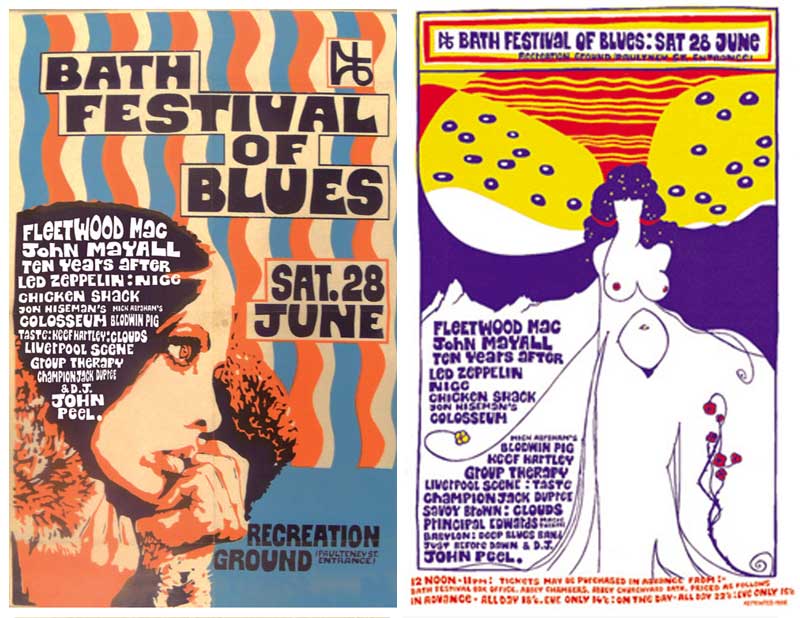

Freddie and Wendy put together a modest bill of new talent: Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Ten Years After, Led Zeppelin, The Nice, Chicken Shack, John Hiseman’s Colosseum, Mick Abraham’s Blodwyn Pig and more.

“Tickets were 18 shillings and sixpence [about 93p],” Freddie told Classic Rock in 2007, “and 14 shillings and sixpence just for the evening [73p]. Led Zeppelin cost us £200 – but [manager] Peter Grant did push me up to £500 before they’d signed the contract.”

According to Bath Festivals, they issued 7,000 tickets but 30,000 people showed up. “It completely took us by surprise,” said Wendy. Back then, most people didn’t even know what festivals were. Wendy rang the ticket offices around the country only to discover they’d all sold out their allocations. Ulp.

“It went very well,” was Freddy’s modest recollection. “It was profitable, it was fun. One of those wonderful 80-degree days, sunny all day. Everyone had just discovered dope so they were very placid.”

Just as well. Security wasn’t exactly tight: to collect money from the walk-up audience, they put a trestle table by each of the gates. That was security. Wendy cycled across the site from one table to the other, collecting bags of cash.

The Bath Pavilion across the road acted as the backstage area. Inside you might have found The Nice playing table tennis with Ten Years After or Chicken Shack whipping Blodwyn Pig at darts. “I think we bought some of them a drink,” remembered Freddie, “but there was no such thing as a rider then.”

There were two stages, about three foot off the ground, constructed the night before. Everything went well until The Nice brought “four brawny bagpipers” onstage. “When they came on and started marching around, the stage started collapsing!” remembered Freddy. “So I got four of my very largest stewards to lie under the stage holding it up while The Nice did their thing. When The Nice had finished, the second stage opened up and Zeppelin came on, and while that was happening I got the carpenters to repair the stage ready for Ten Years After.”

And toilets? They had none. “We just gave them re-admission passes,” said Wendy, “so they could go out into the town, which was about 200 yards away, and use the public conveniences.”

Bath is just 25 miles from Glastonbury and The Bath Blues Festival, along with the Isle of Wight Festival, played a role in shaping the concept of Glastonbury in the mind of Michael Eavis. The Glastonbury festival of 1970 was envisioned as a "son of Bath". Festivals were well and truly on the calendar.

As a result, Freddy and Wendy were determined to make the next Bath festival an even bigger, more glittering occasion. The following year the festival underwent both a name and a venue change. The 1970 Bath Festival Of Blues & Progressive Music took place at the Bath & West Showground.

Shepton Mallet on the weekend of June 27-28. The bill had expanded from a primarily British affair to a fully fledged transatlantic line-up. Canned Heat, Steppenwolf, Pink Floyd, Johnny Winter, Fairport Convention, Led Zeppelin, Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa, Moody Blues, The Byrds, Santana, Dr John and many more were invited to join the fray…

FB: We tried to do it again the next year and the town council was very much on our side. The chamber of commerce thought it was great for Bath because it brought in all this money, but they were worried about that many people descending on the centre – and they were probably right. By that time, Led Zeppelin on their own would have drawn more than 30,000.

WB: We sold the house and a lot of our possessions to pay the bands in advance for the second festival. Crazy! It was a hell of a gamble but I think people did take more chances in those days.

FB: We had to grow in size to compete with the Isle of Wight and I’ve always gone in for overkill. So I put together a programme that I thought would draw a lot of people – which it did.

WB: It was a bit of a panic by then because we’d already signed a contract to have Canned Heat and we hadn’t anywhere to put them! They were big back then and we were determined to get them. But things had changed immensely between ’69 and ’70, because of Woodstock.

It became a free festival because they knocked the gates down. The feeling between ’69 and ’70 was totally different. The kids in ’69 were so nice, so relaxed. By 1970 they’d become, you know, ‘music should be free!’ and we had old Edgar Broughton singing outside – “Out demons out!”

FB: Political militancy had grown enormously in just 12 months. And there were all these ‘revolutionary’ hippies from France there stirring things up. The Isle of Wight festival also got a lot of trouble that year from the French revolutionaries. But they went the whole hog and took on the kids. They put up corrugated iron fences whereas we, like idiots, trying to be nice to the audience, just built up the perimeter fence – two miles of chain-link fence.

WB: The majority were American groups that people in this country just hadn’t seen before – and a lot they haven’t seen since. People like Flock and It’s A Beautiful Day. We had also become very friendly with Bill Thompson, who managed the Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead. It was a very druggy scene but terribly middle-class and correct in other ways.

FB: We also put in an offer for Frank Zappa, who was enormous at that time – as big as Led Zeppelin. But, typically, we didn’t hear any reply to our offer so we assumed he wasn’t doing it. Then the day I collected the posters his manager, Herbie Cohen, rings up and says: “We’ll do it!” We had to reprint all the posters.

WB: All the bands’ fees were much higher for the second festival because we were now competing with the Isle of Wight and we wanted the biggest names. Led Zeppelin’s fee went up from £500 the previous year to £20,000. And Peter Grant insisted their name was double the size of anyone else’s on the poster.

FB: As I’d already given my word to Bill Thompson that that wouldn’t happen, he was very cross with me. But Zeppelin were making it very big in America and we had to have Zeppelin.

WB: They were simply so enormous by then we knew that they’d bring in all the people. The sum of £20,000 was the equivalent [then] of the price of a house in Knightsbridge, I can tell you that!

FB: The first festival had been fun. I enjoyed it enormously. The second festival was no fun at all. It was a horrendous gig for us, we hated it, which is why we never did a multiple-night outdoor event again.

WB: Because it became a free festival. They knocked down the gates just like that and walked in. There were other problems, too. Most of the bands had to drive down some quite small country roads to get there, and a lot of them simply got stuck in traffic. At one point we had Donovan on stage filling in for about four hours – and he wasn’t even billed!

FB: Fairport Convention were stuck in the traffic, but some Hell’s Angels appeared and they got on the backs of their bikes and escorted the band into the festival. And then they promptly took over our security in front of the stage and started beating people up. In fact the only time I went into the stage area in the whole 48 hours was to go and sort the Hell’s Angels out.

I’m not sure how tired or how stupid I was, but I did that on my own. I went and bought them off! I got them all backstage and I said: “Hey, this can’t go on. You’re being an absolute pain. I don’t want you here, I want you to leave. I’ll give you money.”

I forget how much it was but something like 400 quid, I think. “Otherwise,” I said, “I’ve got two or three hundred stewards here,” there were like 40 or 50 Hell’s Angels there, “and I’ve got a team together and we’ll come and sort you out and we’ll sort your bikes out as well, and there’s going to be war here. Or you can take the money and go.” So they took it and went. But, to be fair, they weren’t the American west coast Angels. I wouldn’t have dreamt to take them on.

WB: These were from the west coast of England. With the appropriate accents – “Ooh-arhh!” Subsequently we’ve seen some film [of two of the Angels being interviewed at the festival] and one, halfway through, pops his false teeth out and waves them.

The other is the Hell’s Angel’s leader who turns out to work as an engineer for Rolls-Royce in Bristol, and he actually built his bike by hand. So that partly explains why Freddy didn’t have his head beaten in. What happened next? The phenomenon of the outdoor rock festival continued to grow but the Bannisters, disillusioned by their experiences in 1970, only put on one more, low-key oneday event in Lincoln, in 1971, before temporarily retiring from promotion.

That is, until Freddy “discovered this natural amphitheatre” on the grounds of Knebworth, in 1974. Suddenly they were back in business promoting a series of outdoor shows that would become some of the most famous in the 1970s, headlined by the biggest bands in the world, including The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin.

Memorabilia from the Bath and Knebworth festivals is available from www.rockmusicmemorabilia.com

!["[T]he First and Fifth Amendments Require ICE to Provide Information About the Whereabouts of a Detained Person"](https://images.inkl.com/s3/publisher/cover/212/reason-cover.png?w=600)