Imagine being stuck at the bottom of the North Sea, with an emergency supply of air that is quickly running out, and no immediate help available. Such was the predicament that diver Chris Lemons was plunged into on 18 September 2012, when the umbilical cord that connected him to a diving bell, providing him with gas for breathing, hot water, communications and electricity, snapped, during routine work on a drilling structure at the Huntington oil field, 115 miles east of Peterhead, Aberdeenshire.

What happened next became a sensation inside the global diving community. People were keen to know how Lemons’s employer, Bibby Offshore (now renamed Rever Offshore), had dealt with the situation, so the company commissioned a short industry film, Lifeline, from Floating Harbour Films, in 2013, to, says the production company’s website, “highlight the potentially extreme consequences of an incident in the workplace”.

This has now been developed into Last Breath, a feature-length documentary which uses convincing reconstructions, original footage (there was a wealth of it, captured by different devices in the water and on board the Diving Support Vessel Bibby Topaz), and gripping interviews with some of the key people involved, including Lemons’s team mates, Dave Yuasa and Duncan Allcock, and dive supervisor Craig Frederick, to create a nailbiting tale of survival against the odds.

As compelling as the story is the insight the documentary provides into the unique world of saturation diving: the kind used to get men – and it is only men doing “sat work” in the North Sea at the moment, Yuasa believes – into places you normally wouldn’t be able to with conventional diving. For this reason, it is “the highest paid kind of diving you can do,” he says. “It’s quite a mercenary industry. Most of us, we’re in it to make the money and get out, really.”

Frederick agrees: “It’s a well-paid part-time job. You work four or five months a year, and you get the rest of the time off.” However, he insists, “You couldn’t do it just for the money. You would have to actually enjoy it in some way, because of the privations and lack of privacy.”

The profession draws people from all walks of life. Yuasa started as a scuba-diving instructor in Asia and Cornwall, and then decided he needed a “grown-up” job. He went into commercial diving, working in canals and reservoirs, before moving offshore in Holland. “Then it’s quite a natural kind of career path up with sat diving. As long as you’ve got an aptitude for it, you kind of find your way there.”

Allcock was a speed swimmer at school, who dreamed of being one of Jacques Cousteau’s divers (“Obviously I was a little bit too young at the time”). He ended up pushing paper in the civil service for four years but, following a “bad breakup with a girlfriend”, thought, “Why don’t you try and do what you’ve always wanted to do?” He borrowed £3,000, split between his mother and brother, and, in 1985, went up to the Underwater Centre in Fort William, got qualified, “and never looked back. I absolutely still love it,” he says.

Frederick, a Canadian, realised that diving gave him a way to use somebody else’s money to feed the travel bug he’d developed hitch-hiking across Europe and Asia in 1977. He was just 19 when he started, “and probably one of the youngest guys on every job I went on,” he says. “For a young man, it was a bit of an adventure.” The work took him to the North Sea, West Africa, Asia, India, the Middle East.

Back then “it was a bit of a wild west”, he recalls. “You set your own safety standards and you decided what you would put up with as far as risk. You were your own safety boss down on the seabed. Essentially, the people who were running the industry then didn’t have the training in health and safety, and they do now. It wasn’t their fault, it was just the way it was... That’s why there was quite a few more injuries or near misses.”

Today, the North Sea is the “gold standard for safety,” says Frederick. But with every job “there’s always speed bumps in the road which are going to trip you up, whether it’s the weather, or the visibility, or the tidal conditions, or whatever. So there’s also extra parameters that you have to factor in each time.”

As Last Breath shows so dramatically, things can and do go wrong. Yuasa, whose unflappability and wry humour remind me of the free solo climber Alex Honnold (they’ve both been likened to a Vulcan), says: “We tend to pretend to the people back home that it isn’t dangerous. And I’ve heard people say it’s a very safe job. The fact is, it’s not safe... It’s safe as long as everything goes right. And if it goes wrong, it’s instantly dangerous.”

When asked about the qualities it takes to do the work, Allcock adds being “possibly slightly unhinged” to the mix. When you consider how saturation divers live and work offshore, he has a point.

For the duration of a job, home – or storage – becomes a metal saturation chamber located on a Diving Support Vessel (DSV). For weeks on end, six people (two teams of three divers) share a space that’s so compact, says Frederick, “I don’t think you could legally put six dogs in one [of these tanks]. Look at the rules for a kennel and I bet you couldn’t put six dogs in them.”

Once everybody is inside, the entry hatch is locked and a process known as “blowdown” begins. Because breathing compressed air at the depths at which the divers work would have a narcotic effect, causing cognitive impairment, they instead breathe an inert mix of helium and oxygen called heliox. This is pumped into the saturation chamber, filling the divers’ lungs and saturating their tissues, until the internal atmospheric pressure matches the pressure exerted by the weight of the water at the depth they will be operating. The deeper the dive, the longer the blowdown.

In the past “they’d blowdown at any rate they wanted,” says Allcock, which could cause potentially career-ending problems such as high-pressure nervous syndrome and ear damage, if done too fast.

“Now, not only do we decompress at a very regulated rate, but they blow us down at a very regulated rate, and we have stops.”

One such stop occurs at 10m pressure, when Snoop – “which is actually just Fairy Liquid and water,” he says – is sprayed on every seal, every fitting, every porthole, every door, and everything around the bell that will take the divers to the job, to check for gas leaks. If all seals are secure, the process continues.

“If there was anything wrong, then they could bring us back to the surface [that is in terms of pressure, not actual depth, as the chamber itself goes nowhere] without any decompression problems, sort it, and then blow us down again.”

One amusing effect of heliox is that it makes everyone “doing sat” sound like Pinky and Perky. And the deeper they the go, the higher their voices rise. “It’s sort of like squeezing Perky’s balls,” says Allcock, laughing. “Over 100m, you can’t tell what we’re saying at all!”

Blowdown causes the temperature inside the chamber to climb. Meanwhile, divers’ joints can seize up, “and any kind of old injury you might have had, that seems to come back,” says Yuasa. “I think it’s kind of a little window into old age, really.”

Adds Allcock: “You don’t even know about it until you start moving. If you’re going deeper than 100m, it’s as though, which I’m sure it is, somebody’s compressed your back, and in the morning, or later that night, you can’t even move. It’s horrible. But if you can keep moving your joints on the blowdown, for me anyway, I found it’s not too bad. But maybe it’s just because I’m getting old.”

Tolerance is essential given the confined space, and Allcock reports that “it has been known for fists to fly a couple of times in the chamber. But not in the bell. And not in the water, ever.” Obviously if somebody’s claustrophobic – “a big red line”, warns Yuasa – then saturation diving isn’t for them. Both men know tales of divers suddenly panicking to the point of being unable to function. It’s a rare occurrence, though, and neither has witnessed such extreme behaviour first-hand.

“I’ve heard stories of [it happening to] people blowing down to pretty deep, 150-odd metres,” says Yuasa. “Normally this is pretty early in their career, and maybe their first trip, and they refuse to go, or they even get down into the water, lift the door, and say, ‘No, I’m not going to do it.’ ... But I’ve also heard of people doing it at the end of their career, too. They’ve suddenly put the hat [a diver’s word for helmet] on, and said, ‘I can’t do it any more. I’ve had enough.’ I think once your head goes, it’s gone.”

Going into the chamber is “horrible” for divers, says Frederick, because they know how many days stretch ahead of them (in this case 28). Once they’ve settled into a routine, though, they “completely forget about what’s going on elsewhere. You sleep, you eat, you get up, you go to work, come back, shower, eat, sleep, and then the days just run and run and run.”

“You become institutionalised in there,” claims Yuasa, noting that some people find readjusting to life at home a struggle.

Diving is part of the routine, and when Lemons, Yuasa and Allcock descended in a bell to do the job in the North Sea that almost ended in tragedy, the shift began just like any other.

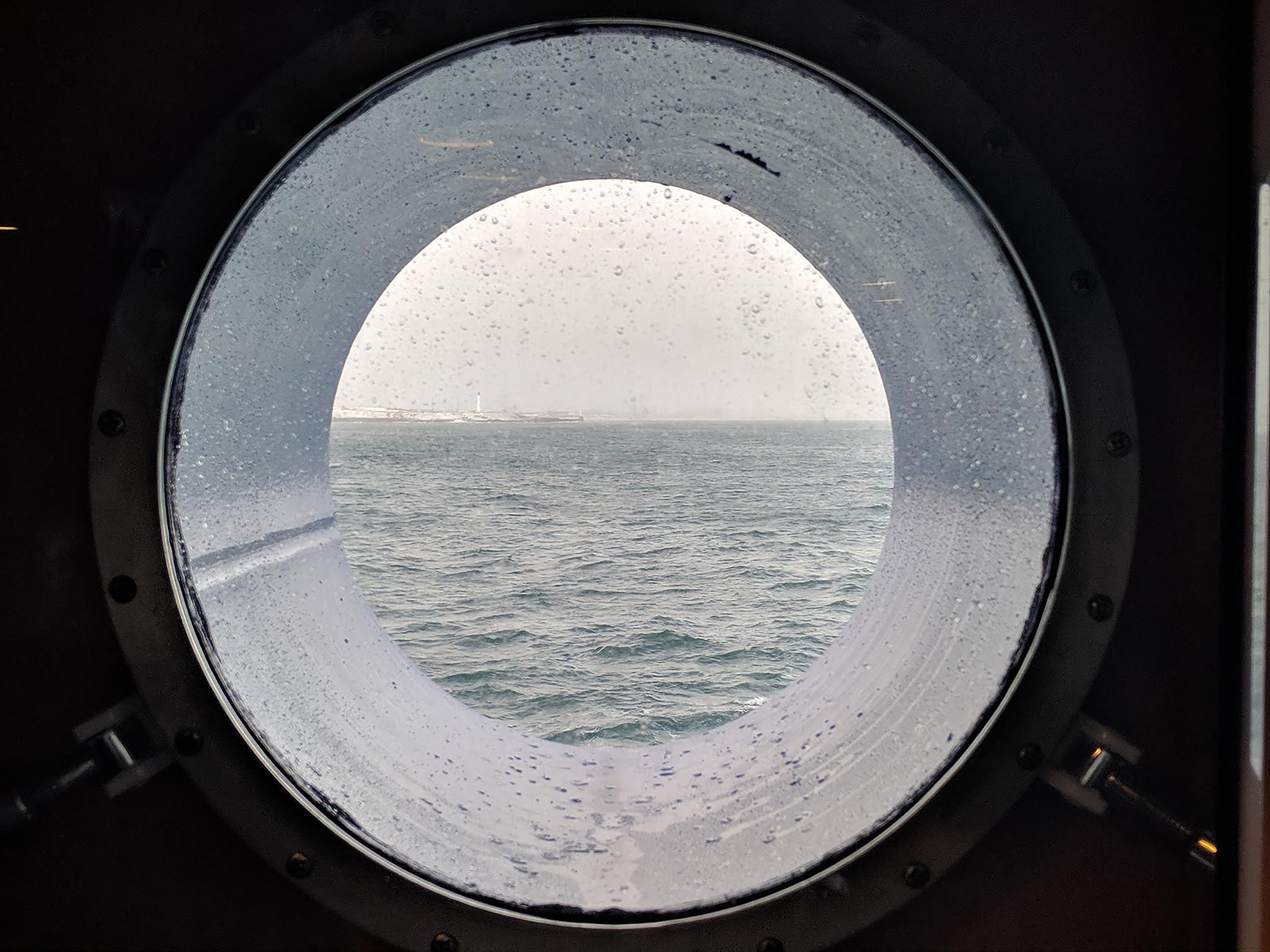

On the surface it was windy, with waves that look dramatic in the documentary but in reality were “pretty standard” for September, says Frederick. The conditions were “not even at the outside limit [for diving]. There was no question of us stopping because of the weather.”

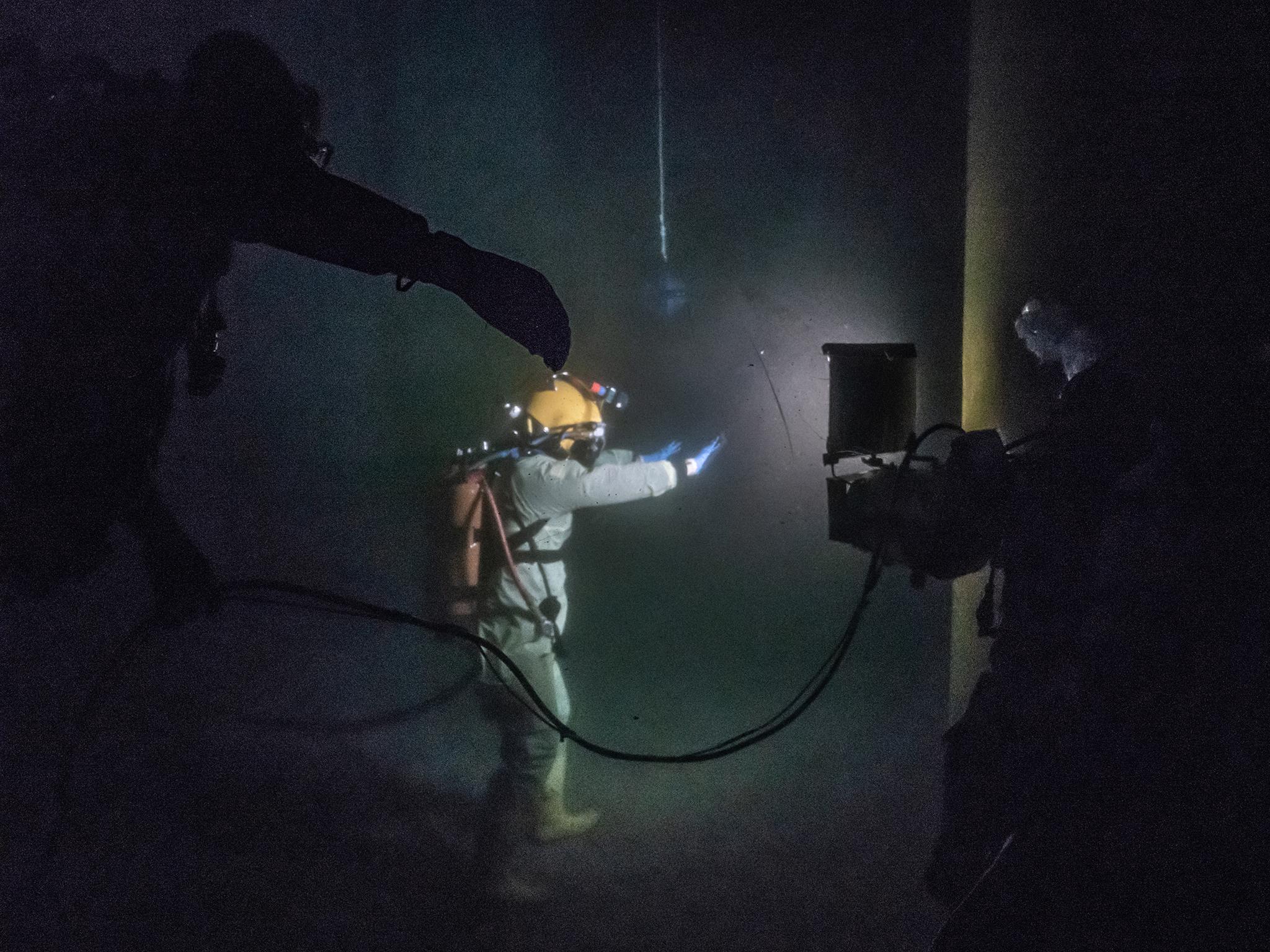

Yuasa and Lemons dropped off the bell around 10 minutes apart, staying tethered to it by 50m-long life-supporting umbilicals, and made their way inside the framework of an (approximately) 11m-high subsea drilling template structure. The work to be done was straightforward: “They were going to remove some pipework and replace it with another type of pipework,” says Frederick, “and were essentially commissioning a series of well heads. That’s our bread and butter.”

Around 45 minutes later, an amber warning light on the Bibby Topaz indicated that there was a problem with the Dynamic Positioning (DP) system used to stop the vessel drifting. Frederick told the divers to get back to the bell, expecting a solution would be found. Instead, the alarm almost immediately escalated to red, indicating an unprecedented catastrophic failure. The divers were inside the template, recalls Frederick. “So, I just kept saying, ‘You’ve got to get back to the bell! Get on top of the structure!’”

After scrambling up, Lemons realised his umbilical was snagged on something and he was unable to move. He requested slack, but it was already too late. The Bibby Topaz was being blown off station and dragging the bell, pulling his umbilical tauter and tauter.

“It was so tight,” says Allcock, who was acting as bellman on the shift and providing support from inside the bell. “There was no way I could even get my fingers in to pull [more umbilical] off, let alone pull it over the top of the horns where it’s wrapped up ... It was literally pulling the rack, which is like four-inch stainless-steel bars, off the wall. For a moment I thought it was going to pull me out of the hole to them. I literally jumped on the chair at the opposite side of the bell, and pinned myself to the roof, like Spider-Man, just trying to get out of the way.”

Yuasa attempted to reach Lemons but even with extra umbilical, he could only get within a metre of him. He explains that umbilicals are comprised of a number of rubber hoses and a cable for electricity, lighting and so on, wound together like a candy cane. Lemons’s was being stretched, and Yuasa watched “it getting thin, which I’d never seen before”. All of a sudden, he heard a bang, which he assumes was the “armour-plated” cable snapping, followed by “quite a lot of tearing, which would have been the other ones parting, one by one. That was quite memorable, actually,” he says drily.

In dive control on the Bibby Topaz, Frederick’s screens went dead as the tear temporarily shorted out the bell. He could still contact Allcock, though, using a sound-powered phone, and told him to pull in Lemons’s umbilical. “I wanted to see that it was severed rather than it pulled off his harness and we ended up with his hat,” he says. “As long as he had his diving helmet, then he had a good chance of surviving.”

When the shredded ends came up through the bottom of the bell, Allcock, who knew Lemons and his then-fiancée, Morag, onshore, “didn’t know whether to spew, shit, or cry. I knew in my heart of hearts, when I started pulling his umbilical in, that he wasn’t on the end. But until I got both hoses in my hand, one by one, I literally felt sick.” Turning off his friend’s gas supply “felt like I was killing him”.

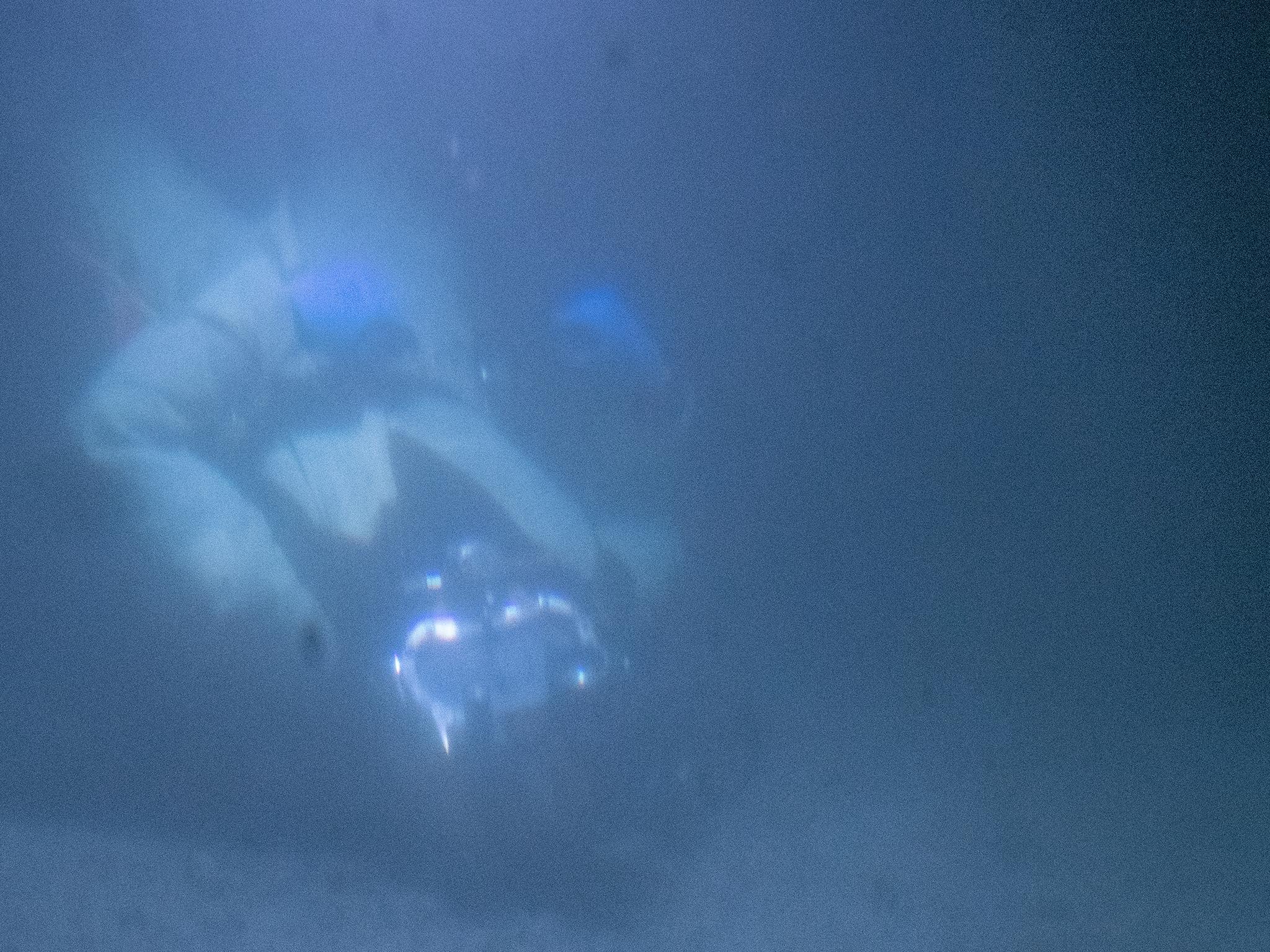

As the bell got dragged away by the DSV, Yuasa found himself being tugged off the structure. “It was quite a long ride,” he says. “I was kind of in mid-water. So, I made my way back to the bell, which was a physical effort, but it was the only place I could have gone anyway, really.”

Sitting underneath the bell awaiting further instructions, Yuasa peered into the inky darkness. No one knew whether Lemons was dead or alive. “I was thinking, ‘I hope it doesn’t hurt. I hope it’s quick.’ It’s a bad death, isn’t it? For a start, you’re alone. So I hoped it was quick and that it hadn’t hurt. And I was glad it wasn’t me.”

Lemons had a 10-minute emergency supply of gas, by Frederick’s reckoning. Legally, he only needed five. While other crew were trying to control the ship manually (the system was eventually brought back online by, of all things, turning it off and on again), Frederick says his “challenge was not to give [Allcock and Yuasa] too much information. It looked pretty hopeless, as far as they were concerned, so I couldn’t tell them we were 250m from Chris and we hadn’t gained control of the ship. So, essentially, I took it on myself to gee them up and say, ‘Yes, we’re making progress. We’re going to get it back there. I have total confidence this isn’t a recovery mission, it’s a rescue mission’.”

Everyone knew that Lemons’s chances of surviving were growing slimmer with each passing minute. Yuasa suggested trying to rescue Lemons from 50m away. “I said it just wasn’t feasible,” recalls Frederick, who didn’t want to risk another diver’s safety.

Eventually, after around half an hour, the ship returned to above the structure. Yuasa dropped off the bell again and found Lemons, who was lying atop the template, his gas having long run out. “I didn’t expect him to be alive. Why would you?” he asks rhetorically. He made sure that Lemons wasn’t still connected to the structure, and then shared his breathing supply with the stricken diver by putting a pipe from his own umbilical into Lemons’s helmet. The same tube had been giving Yuasa buoyancy; they were now both dead weights.

Yuasa fed Lemons into the bell to Allcock, who was shocked by what he saw when he removed his helmet: “He’s a bald guy, he’s half frozen to death, and he’s gone as blue as a pair of denim jeans.”

Allcock sat Lemons up as best he could in the limited space inside the bell, stuck his fingers up the unconscious man’s nose to block his nasal passages and keep his head erect, and performed mouth-to-mouth. Almost seven years later, he still sounds amazed at what happened.

“Chris took one of those sorts of breath” – he demonstrates with a sharp gulp of air – “which to me was like New Year, crackers, fireworks, you name it. Everything. It was like, ‘Bloody hell! He’s actually alive!’”

Yuasa’s concern while waiting to retrieve Lemons had been that if they hadn’t managed to resuscitate him in the bell, then they’d have to carry on trying in the chamber system “whilst he was re-warmed – because you’re not dead until you’re warm and dead. Then we’d have been stuck in the chamber with a dead body for three days whilst we all decompressed. When he turned out to be OK it was a massive relief, if somewhat anticlimactic.”

Decompression appears to be one of the worst parts of the job generally. There is no diving to break up the monotony of life in storage and all the divers can do is wait for days on end as they’re gradually brought back to surface pressure. It takes less time to return from the moon than it does to decompress, and home feels agonisingly, tantalisingly close.

For this job they’d been blown down to 100m, which meant three or four days in “desat”, whatever happened, says Yuasa.

“And it really doesn’t matter if your house has burnt down or your kids are in hospital, you can’t get out any quicker. So even though you’re really just on the other side of a bit of metal to everyone else, you feel a long way away from the people on the outside.”

Clearly, in saturation diving, pressure comes in many forms.

‘Last Breath’ is in cinemas now