The controversial Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill is being presented by its architect, ACT Party leader David Seymour, primarily as a matter of lawmaking – a clarification through legislation.

The bill seeks to redefine the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi – established by decades of case law and jurisprudence – and instead enshrine new principles in law.

But the bill goes deeper than that, and touches on delicate but fundamental questions of what it means to be a New Zealander.

In the heated debate since the bill’s introduction, two ideas of national identity come head to head. And the implications for social cohesion and the quality of democratic debate are serious.

Equal and democratic vs bicultural nation

For the first few decades of colonial settlement, New Zealand’s identity was contained within an imperial one. The colony aspired to be a “Britain of the South”. It was only from the 1950s that European New Zealanders began to develop a distinct identity.

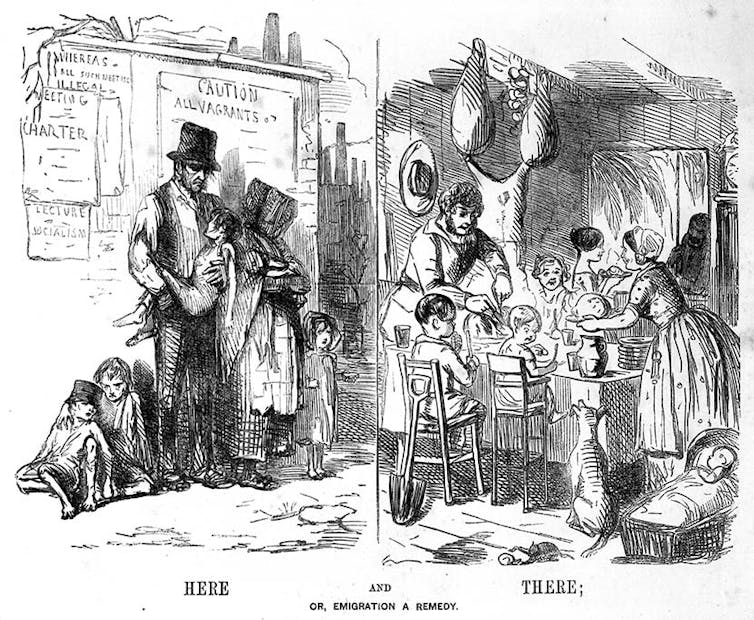

Pākehā national identity was constructed around ideas of political and economic egalitarianism. These emphasised hard work and social mobility, and portrayed New Zealand as a “land of opportunity” or a “classless society”.

But these notions of the “equal and democratic” nation excluded Māori and perpetuated a monocultural vision of New Zealand. In fact, for Māori, the process of colonisation was anything but an egalitarian experience.

Not only did the loss of ancestral land – through forceful confiscations and the introduction of private property laws – fuel poverty and economic inequality, but Māori were also denied the political rights promised to them in the Māori text of te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Grievances over cultural assimilation, historical injustices and political self-determination galvanised a growing Māori protest movement. In the 1970s and 1980s, governments responded by creating the Waitangi Tribunal and by fostering a bicultural understanding of New Zealand national identity.

Since then, this shift towards greater biculturalism has happened on several levels: weaving Māori culture and language into the fabric of the nation, educating the public about the Waitangi Tribunal’s role in addressing historical wrongs, and promoting the Treaty as the main symbol of Aotearoa-New Zealandness.

Recently published survey data show the bicultural understanding of national identity has taken root among younger generations: 85.4% of those aged 18 to 34 agree that “Māori culture helps to define New Zealand in positive ways”, compared to 63.1% of people aged 65 and over.

Similarly, the younger generation is more likely (59.4%) to accept that “we as a nation have a responsibility to see that due settlement is offered to Māori in compensation for past injustices” than the older generation (37.8%).

The threat of culture wars

The Treaty Principles Bill magnifies the differences between these two different ideas of New Zealand national identity.

Seymour says “the Treaty must be consistent with a liberal democracy and give equal rights to each person that has to live in this country”. As such, the bill aligns with the “equal and democratic” image of New Zealandness.

What is more, by implicitly framing the Treaty as a governance agreement, rather than a partnership between Māori and the Crown, the bill challenges the very interpretation of the Treaty underpinning the bicultural vision of the nation.

New Zealand has previously experienced the kind of divisions so-called culture wars thrive on, for example in public debates about the use of te reo Māori in public life or officially renaming the country Aotearoa.

But the Treaty Principles Bill threatens to inflame a battle over national identity, deepening those divisions and reinforcing them through overlapping generational differences.

As the sociologist James Davison has argued, American-style culture wars, which have spread to other countries, have the potential to “break democracy”.

Not only do they exacerbate a sense of “us versus them,” but they also narrow political discourse. The focus shifts towards emotionally laden, symbolic disagreements, away from real social and economic issues.

Bicultural egalitarianism

At one level, avoiding a culture war escalation requires holding accountable those politicians who engage in divisive rhetoric. But it might also involve reducing tensions by emphasising shared values across the two interpretations of New Zealand identity.

One possible way to do this is to stretch the idea of egalitarianism – which is central to the image of the “equal and democratic” nation – beyond its usual meaning of equality of opportunity.

If we expand its definition to include equality of outcome, the bicultural commitment to provide financial reparations as a means to improve the economic situation of Māori – which continues to be marked by colonial legacies – fits the “equal and democratic” vision.

We could also broaden egalitarianism to mean “epistemic” equality, which stresses the importance of extending equal value to diverse ways of seeing and knowing about the world.

This could help develop a more inclusive narrative of national identity that combines notions of egalitarianism with biculturalism – manifested, for example, in bicultural governance arrangements informed by mātauranga Māori, a Māori worldview.

Olli Hellmann does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.