After weeks of anticipation, it’s finally official: the Bureau of Meteorology has declared another La Niña is underway. This means Australia’s east coast will likely endure yet another wet, and relatively cool, spring and summer.

It’s the third La Niña event in a row. This is rare, but not unheard of. Triple La Niñas have also occurred in, for example, 1973–1976 and 1998–2001.

The past two La Niñas mean water catchments are already full, and soils are sodden from Noosa in the north through to Lismore and the Hunter Valley in the south. It means more flood events are likely in the coming months.

The bureau’s declaration will be unwelcome news to many people – especially those in parts of New South Wales and Queensland still recovering from recent floods. So what else can flood-weary Australians expect in the coming months? And is a fourth La Niña on the cards?

A potentially mild La Niña

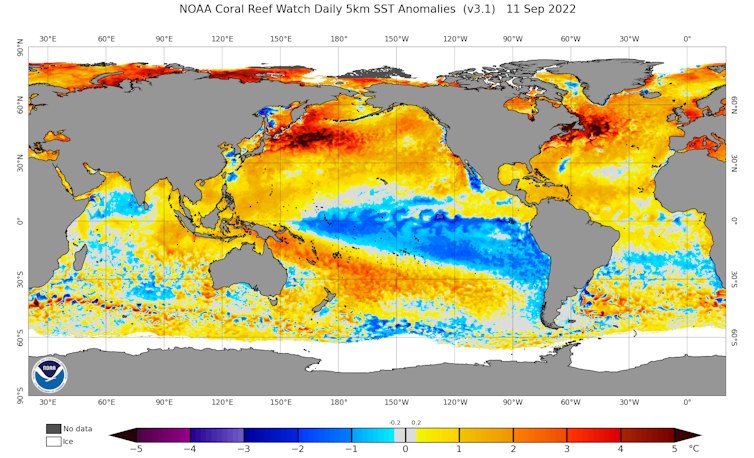

La Niña is part of a natural climate cycle over the tropical Pacific Ocean. Sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific vary between being warmer than average (El Niño) and cooler than average (La Niña).

This variability has worldwide effects as it shifts weather patterns – bringing droughts to some regions and floods to others.

For most of Australia, La Niña raises the chance of rain. It has contributed to some of Australia’s wettest ever conditions, and some of the driest in the southern United States across the Pacific Ocean.

The Bureau of Meteorology says this La Niña may peak during spring, and return to neutral conditions early in 2023. Most seasonal prediction models are suggesting this La Niña event will be weaker and shorter-lived than the last two.

Typically, stronger La Niña seasons are associated with more extreme rainfall in eastern Australia. So hopefully a mild La Niña comes to pass and flood-hit regions avoid the worst of the summertime rain, at least.

La Niña is a part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a natural phenomenon. We know these events have occurred in the past – before large-scale greenhouse gas emissions from human activities.

We don’t yet know how La Niña may change as the planet continues to warm, but evidence suggests climate change may make La Niña (and its counterpart El Niño) events more frequent and intense.

And research from earlier this year suggests relationships between La Niña and regional climate may become stronger over many parts of the world, including much of Australia. This could mean Australia feels the force of La Niña and El Niño events more in future as the planet continues to heat.

Three climate forces at work

It’s not just La Niña affecting Australia’s climate at the moment. Two other natural climate forces are also in play: the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Southern Annular Mode.

The Indian Ocean Dipole is characterised by variable sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean, and the Southern Annular Mode by the positioning of winds and weather systems to Australia’s south.

We’re currently in a “negative” Indian Ocean Dipole and a “positive” phase of the Southern Annular Mode.

These all have different effects on the Australian climate. In springtime, these conditions – in combination with La Niña – are conducive to more rain in eastern Australia.

We saw all three of these phenomena occur simultaneously in the spring of 2010, when eastern Australia experienced record high rainfall.

It’s too early to say where exactly in Australia is most likely to experience flooding this spring. While La Niña, the negative Indian Ocean Dipole and positive Southern Annular Mode raise the chances of rainfall, individual weather systems and their trajectories will determine where the worst is located.

What does La Niña mean for drought and bushfire?

One positive aspect of La Niña is it keeps drought out of the picture for the time being. Some of Australia’s worst droughts are characterised by a lack of La Niña or negative Indian Ocean Dipole conditions over several years. Eastern Australia is unlikely to experience severe drought in the near future.

The La Niña conditions also reduce the likelihood that we’ll see a bad bushfire season in eastern Australia this coming summer.

But it isn’t all good news. La Niña and the other climate influences raise the chances of plant growth and greening in eastern Australia. And this could provide fuel for future fires once conditions dry out again.

Historically, major bushfire seasons in eastern Australia have often followed La Niña events. In 2011, after a La Niña and very wet conditions, we saw some of the biggest fires on record.

A background trend towards hotter, drier weather due to climate change could spell trouble down the track.

Another effect of the triple La Niña is that we haven’t seen record high global-average temperatures since 2016 (noting that 2020 and 2016 are almost tied). This is despite our continued very high greenhouse gas emissions, which have rebounded since the pandemic-associated dip.

La Niña typically reduces global-mean temperatures slightly by cooling a large area of the Pacific Ocean – but this is a temporary effect. Record high global-average temperatures will come again soon, and are more likely when the next El Niño occurs.

Read more: 2021 was one of the hottest years on record – and it could also be the coldest we'll ever see again

Could we have a fourth La Niña?

Many Australians hoping La Niña was behind us for a few years now have to contend with a third in a row.

While we’ve seen triple La Niña events before, we have never seen quadruple La Niña in the historical record. This doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen. In fact, the 2001-2002 season that followed the 1998-2001 triple La Niña wasn’t a long way off from being yet another La Niña.

For now, we must prepare for a wet spring and possibly another wet summer to come.

Severe flooding is more likely than usual in already flood-hit zones, so lessons learnt from the devastation caused by the recent floods should be put in place.

Read more: No, not again! A third straight La Niña is likely – here’s how you and your family can prepare

Andrew King receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.