When I was growing up in the 1970s in Chennai, in southern India, the Anglo-Indian girls in my class at the convent had English names such as Dorothy, Bridget and Geraldine. They looked Indian, but spoke English with a distinctive accent, and they prayed at the school chapel.

When I visited their homes, I was always impressed by how spick and span they were. They were filled with lace curtains, gleaming English crockery, runners and carpets. The families almost always owned a piano, loved to dance, and were hospitable and warm.

With their mix of Western and Indian names, cultures and complexions, these young people were the product of the centuries-long British domination of the country.

The offspring of British colonists and Indians became their own distinct community known as Anglo-Indians: they lived in India, but they were Christians, had a Western lifestyle and spoke English as their mother tongue.

These days, though, the Anglo-Indian community is fading quietly into the twilight. There are still an estimated 325,000 of them still living in India, but most are now almost indistinguishable from their Indian friends and neighbours. Many live in mixed neighbourhoods, the women wear saris or shalwar kameez, and the children can speak Hindi.

These descendants of the British Raj have little relevance in the modern South Asian state. In 2019, two nominated parliamentary seats reserved for Anglo-Indians were abolished.

Officially categorised by the government of Viceroy Lord Charles Hardinge in 1911 as “those of mixed blood – children born of European fathers and Indian mothers, and children of their offspring”, Anglo-Indians evolved into a distinct community known for working on the railways.

The hybrid culture encompassed fashion, music and food, with dishes such as jalfrezi – which started as a cold meat dish fried with lots of onions and some chillies – mulligatawny soup and its own version of a railway curry, originally served in the first-class cars of the Indian railways.

Bangalore-based Bridget White Kumar, 68, the author of eight books on Anglo-Indian cooking, has been on a mission to revive forgotten recipes of the community. She grew up in the Kolar Gold Fields in southern India, where people from different nationalities worked together.

“It was the best mix of colonial India and the new, emerging independent India,” she says. “We Anglos were a fun-loving, gregarious lot, always opening our kitchens and hearts to guests, rarely sending them away without a meal.

“I married an Indian whom I met at college and it created a stir in those days, our inter-caste marriage. As a family we had meals that were uniquely Anglo-Indian. A typical Sunday lunch would be yellow rice [coconut milk rice with turmeric] with meatball curry. Lamb chops, roasts and pies, as well as desserts like caramel custard and bread pudding, were favourites.

“Kedgeree [a Scottish dish of rice and fish] is the adaptation of the Indian dish kichdi – a rice and lentils one-pot meal. We Anglo-Indians added fish flakes and hard-boiled eggs to it,” she adds.

When British traders and soldiers first arrived in India in the 1600s, many of their wives stayed home, reluctant to make the long sea voyage with their husbands. Directors of the East India Company, the trading company that seized control of large parts of India before handing the reins to the British government, encouraged the firm’s employees to take local women as their wives.

The offspring of these unions were referred to by derogatory names such as appa kaari – “the ones who sold hoppers”, a type of south Indian pancake – half-castes, or eight-annas, there being 16 annas in an Indian rupee. As time went on, British officials began to find wives among the daughters of the Anglo-Indian families.

By the late 19th century, after the Suez Canal (a canal that links the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea) opened and the voyage to India became less arduous, British women arrived to join their husbands or seek marriage prospects among British men posted in the country. They brought with them class and race snobbery, and frowned on the children of mixed descent, maintaining the separation between the British and Anglo-Indian communities.

Many Anglo-Indians left the country after independence in 1947, and the 1950s and 1960s saw a steady stream of departures as many emigrated to Britain, Australia, Canada and the US. Government financing for separate Anglo-Indian schools was stopped in 1961, and the slow incorporation of Anglo-Indians into the broader community continued.

Famed Anglo-Indians today include actor Ben Kingsley, entertainers Cliff Richard and Engelbert Humperdinck, and the former Olympic athlete Sebastian Coe.

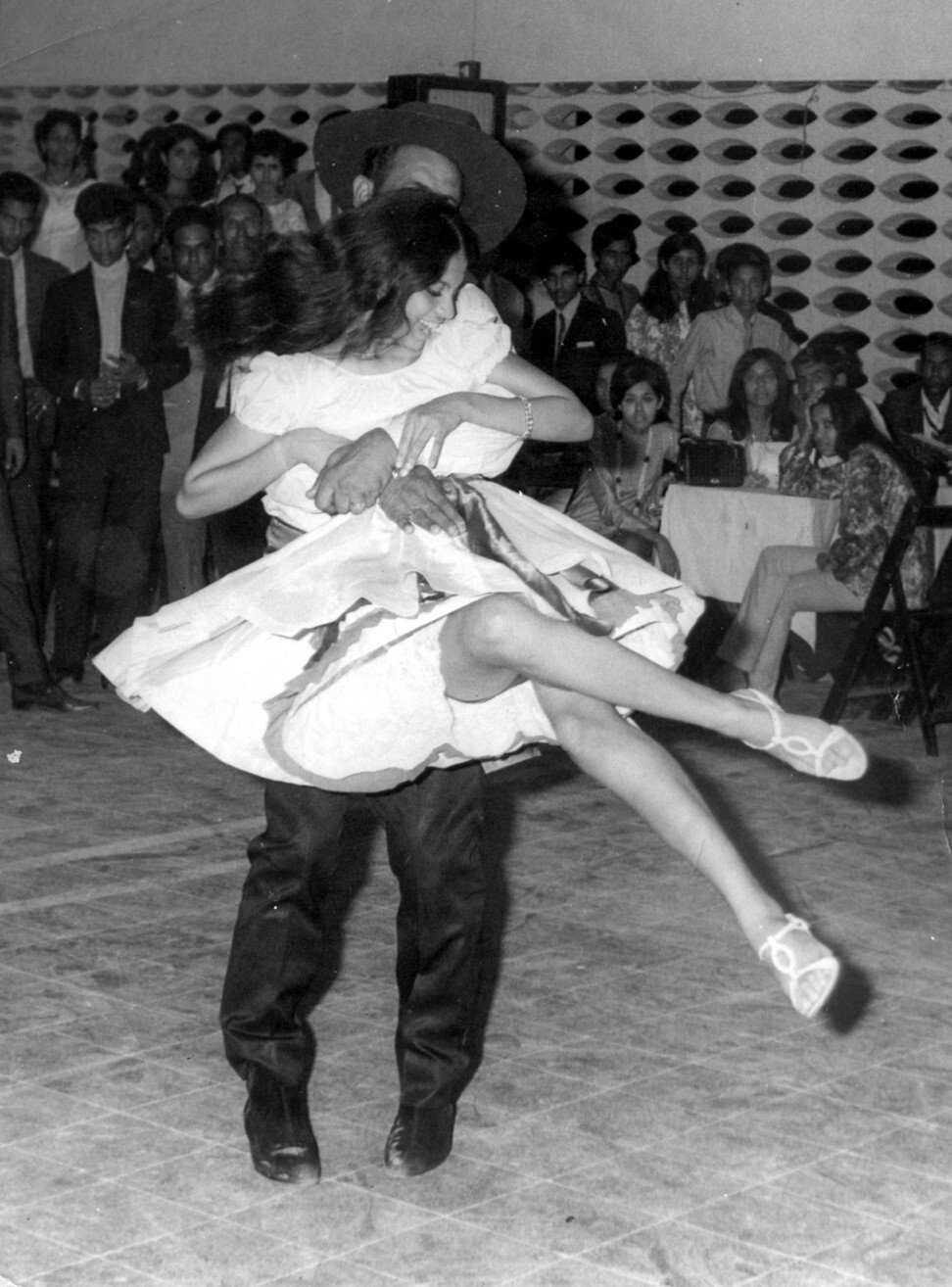

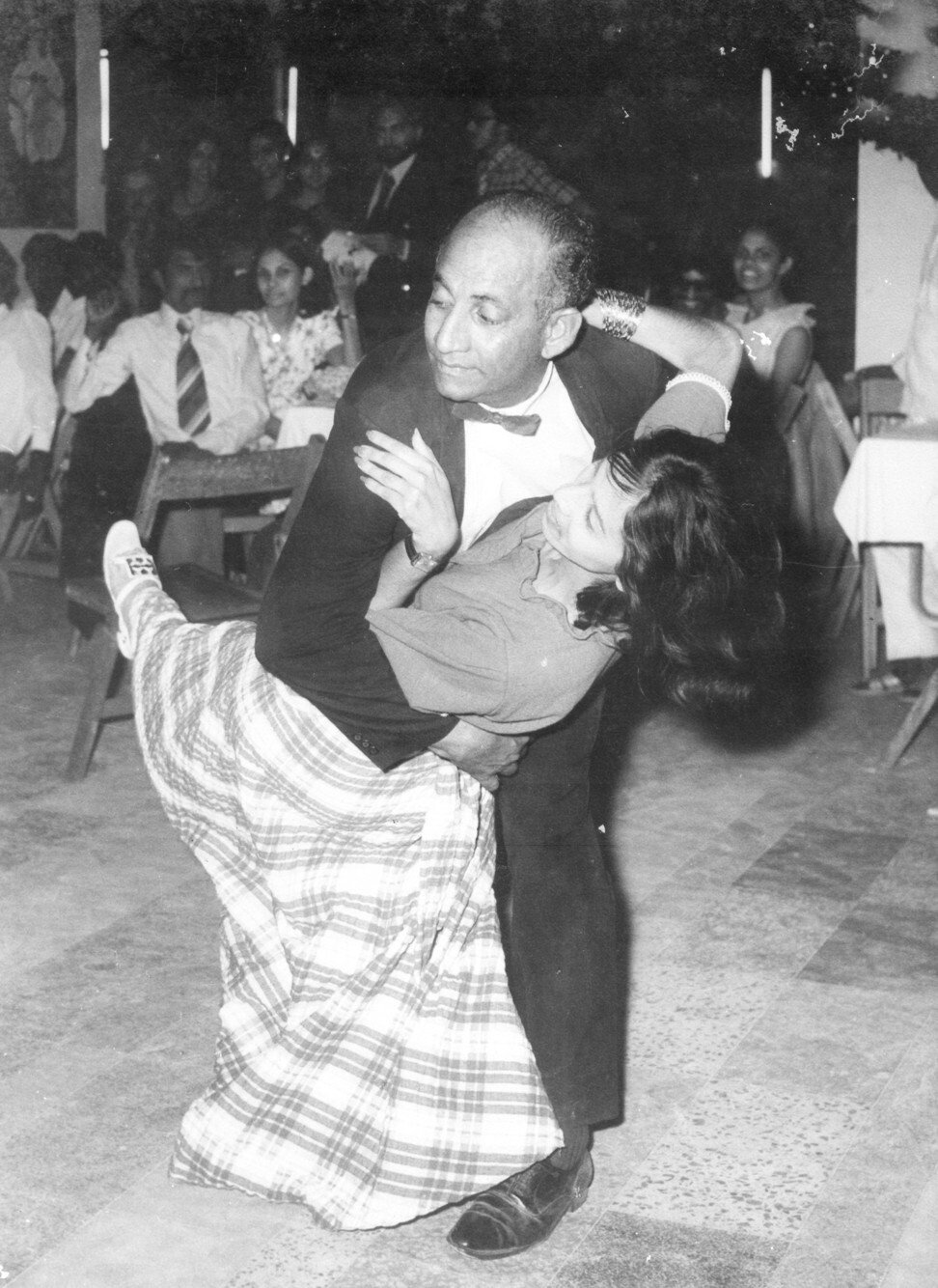

Engineer Sudhir Krishna, 58, who grew up in Bangalore in the ’70s, remembers the community with affection. “As young boys we were in awe of Anglo-Indian women, who wore bright lipstick, dresses, drank and went out unchaperoned on dates,” he says. “They were fun-loving and articulate. The community as a whole was gregarious and warm, always serving a drink and snack to anyone who dropped in, and their Christmas balls were legendary.”

Once called the “railway people” because of their overwhelming presence working on India’s railways, Anglo-Indians were employed as engine drivers and firefighters, and lived in railroad towns built for them by the British. Nearly every Anglo-Indian today has an ancestor who worked on the railways.

Chennai-based Augustine Roy Rozario, 62, worked for the railways for four decades. “Though we Anglo-Indians are by religion Christians, we are a distinct community by culture, and the government needs to protect us as a minority, for us to thrive and do well,” he says.

Anglo-Indian Betty Colquhoun Grant, 70, also based in Chennai, has been a teacher for more than 40 years. “I am the only one from my family who is still in India,” she says. “Seven siblings are abroad, from Australia to Canada. I am nostalgic about the past, where dances and celebrations were so common in this friendly community. Our food is still our strong connection to the community, from hoppers and stew to yellow rice and meatball curry with a fiery red chutney called ‘mother-in-law’s love’.

“We have assimilated so much into India, and now more modern Indians dress like Anglos with dresses and short hairstyles, and more Anglos are in traditional clothes like saris and salwars, so one cannot really make out who’s an Anglo-Indian any more.”

Though many Anglo-Indians have integrated into mainstream society, others continue to live in small enclaves, including Austin Town in Bangalore and Perambur in Chennai. In Kolkata, more than 100 Anglo-Indian families live in the Bow Barracks, a tumble-down, red-brick block of flats in a back alley in the city centre.

Harry MacLure, 61, a writer and filmmaker based in Chennai who publishes a quarterly Anglo-Indian community magazine, has Scottish roots. His Anglo-Indian grandmother was in a band that played in cinemas to accompany the silent films of the era, his Anglo-Indian grandfather was a much-sought-after piano-tuner and his uncle was a famous jazz musician.

“I was born in Trichy, which in those days was a big Anglo-Indian hub because of it being a train junction,” he says. “My father was a railway engine driver, and we moved to Chennai for better schools and jobs. I have memories of huge dance parties in Chennai, with musicians, bands and a festive atmosphere. Many old-timers used to make a yearly journey by boat to visit the Our Lady of Mount Carmel [Shrine] in Kovalam. And in typical Anglo style, they would then take a few guitars and play music, and dance on the beach after their church visit.

“Anglo-Indian women were the first Indian women to embrace careers. As teachers they were the backbone of the English-medium schools in the city. The smart, efficient Anglo-Indian secretary was a most valuable asset in corporate offices.”

When MacLure organised the 11th World Anglo-Indian Reunion in 2019, it drew more than 1,500 people from the Anglo-Indian community from Canada, Australia and all over India.

“We strive to keep our culture and heritage alive through such events,” he says. “Our community is becoming increasingly diluted, with cross-community and cross-religion marriages becoming popular with the youngsters.”

Even so, MacLure believes, he is confident the community will survive. “The youngsters still love Anglo-Indian culture, from music and food to church visits and choirs,” he says. “They will definitely take this precious culture forward.”