Henry Kissinger, who turns 100 on May 27, is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in 20th-century international relations. The German-born American diplomat, scholar and strategist has left an indelible legacy in global politics that continues to act as a bookmark for international relations scholars, students and today’s practitioners of statecraft.

From the late 1960s, Kissinger played a momentous role in shaping US foreign policy and navigating the complex dynamics of the cold war era. His contributions to international relations have had a lasting impact, earning him recognition as a visionary strategist and diplomat.

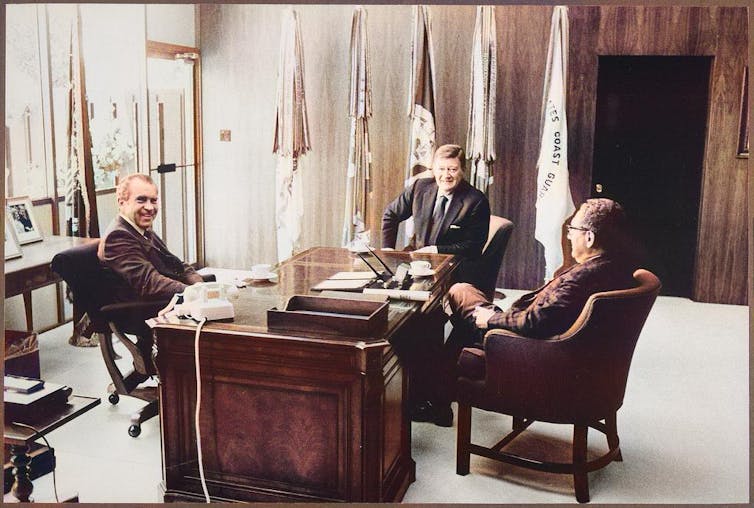

Few would disagree that Kissinger’s influence on US foreign policy has been immense, importantly as a thinker and academic. But his most significant impact was through his work as secretary of state and national security adviser to US presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.

One of his key contributions was his work towards US rapprochement with the People’s Republic of China, planning Nixon’s historic trip to China in 1972 through covert negotiations and deft diplomacy. It was a milestone event in US foreign policy that has shaped Washington’s engagement with Beijing since.

Read more: Nixon-Mao meeting: four lessons from 50 years of US-China relations

Kissinger’s participation in negotiations for the Paris peace accords from 1968 to 1973, which effectively ended the direct US involvement in the Vietnam War, was another key achievement. His relentless efforts in shuttle diplomacy between the US, North Vietnam and South Vietnam, contributed to establishing a ceasefire and evacuating US soldiers, ending direct US involvement.

But despite the accolades, triumphs – and even the Nobel peace prize in 1973 for his contribution to the Paris accords – Kissinger’s record and legacy are controversial. There has long been a debate concerning Kissinger’s approach to international affairs, which according to his many detractors often overlooked ethical considerations.

Concerns about links to violations of human rights and the undermining of democratic values were sparked by his backing for authoritarian regimes such as Chile under Augusto Pinochet. Regardless, Kissinger never wavered in his conviction that his diplomacy should put US interests first while appreciating the complexity of the international scene.

Foreign policy

From his days in government, and then through his continuing influence as a renowned scholar, Kissinger’s strategic thinking and diplomatic approach have shaped US foreign policy in significant ways.

The biggest contribution Kissinger made to US foreign policy was his advocacy for “realpolitik”. He believed that the US should base its foreign policy decisions on a clear and systematic assessment of power dynamics and the pursuit of geopolitical stability.

It was an approach that emphasised the pragmatic pursuit of national interests instead of a strict adherence to abstract ideological principles.

The key feature of this realpolitik was the importance of maintaining a balance of power, believing the US should actively engage with other major powers to prevent any one nation from gaining hegenomy or threatening US dominance.

This approach shaped his handling of major geopolitical events during the cold war, such as the aforementioned normalisation of the relations with China as well as the development of a détente policy towards the USSR in the early 1970s. This perspective also emerged clearly in his approach towards the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Kissinger also made significant contributions to arms control and nuclear non-proliferation efforts during his tenure at the state department. His thinking on nuclear deterrence emphasised strategic stability and the need to prevent proliferation.

In this sense, his emphasis on negotiations and diplomatic engagement – intensified by his shuttle diplomacy method – managed to reduce the nuclear threat.

He played a pivotal role in negotiating the strategic arms limitation talks (Salt) in the 1970s, which resulted in the landmark agreements Salt I (1972) and Salt II (1979), fostering stability in US-USSR relations.

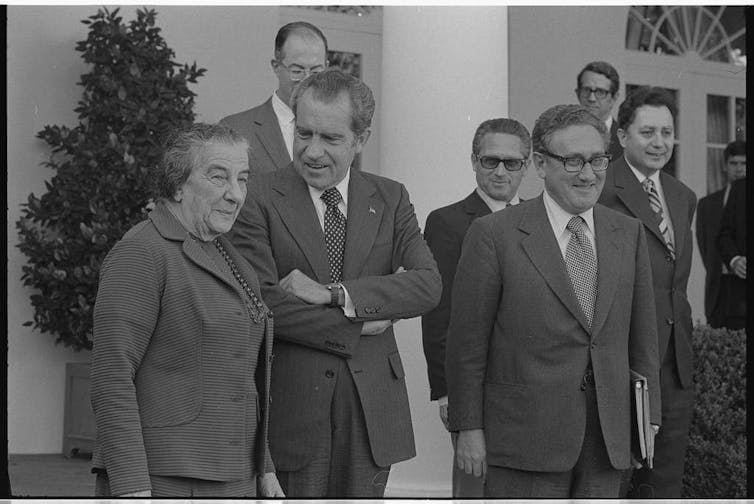

In the Middle East, his shuttle diplomacy once again demonstrated his ability to bring adversaries to the negotiating table, notably during the Arab-Israeli conflicts of the 1970s and the negotiation of the Sinai II agreement in 1975, which – temporarily at least – stabilised relations between Israel and Egypt.

J'accuse: Kissinger’s critics

But Kissinger’s legacy has also attracted foreceful criticism. Among his most vocal and persistent critics was the late British writer and journalist Christopher Hitchens. Hitchens’ book “The Trial of Henry Kissinger” presented a series of arguments about alleged war crimes committed by his American “nemesis”.

Hitchens accused Kissinger of disregarding international law and violating the sovereignty of many nations. His alleged involvement in controversial military actions such as the secret bombing campaigns of Cambodia and Laos has drawn substantial criticism and raised concerns about accountability and transparency in US foreign policy decision-making.

Moreover, America – under his guidance – also stands accused of launching in covert operations to overthrow the legitimately elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, in 1973 in order to install Pinochet), and of turning a blind eye to human rights abuses that occurred during Pinochet’s regime.

Similarly the country’s ostensible support for the Suharto dictatorship in Indonesia disregarded human rights and basic ethics. Of this, Kissinger had this to say in a interview with The Spectator in 2022:

I am, by instinct, a supporter of a belief that America – with all its failings – has been a force for good in the world and is indispensable for the stability of the world. It is in that region that I have made my conscious effort.

Despite all the criticism, Kissinger endured and remains a respected international relations scholars and advisor to this day. After leaving government in 1977, he reentered academia, serving as a professor at Harvard University, where he had previously earned his doctorate in government. As a scholar, Kissinger wrote several influential books, including Diplomacy (1994), On China (2011), and World Order (2014).

That he was invited to address the World Economic Forum at Davos this year shows that, although divisive, even today Henry Kissinger remains a highly influential figure.

Anurag Mishra is affiliated with ITSS Verona.

André Carvalho and Zeno Leoni do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.