The life of King Henry I of England could be mistaken for a subplot in "Game of Thrones": He acquired the throne after bloody wars with his brothers, was as well-educated and cunning as he was harsh and ruthless, and ultimately died in a rather undignified manner: gorging himself on a quite disgusting eel-like fish that resembles nothing more than a teethed funnel with a tail.

"There is a quaint tradition that the city of Gloucester sends the Monarch a pie made out of lampreys that goes back to the Middle Ages."

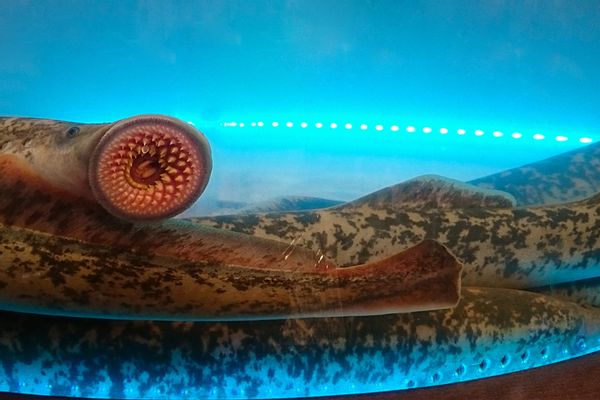

Meet the lamprey, an elongated creature with an ancient lineage as noble as that of any monarch. Unlike the eels that they so closely resemble, lampreys do not have jaws or even bony skeletons; like sharks, their bodies are instead supported by an infrastructure of cartilege. Lampreys have existed as far back as the age of the dinosaurs, and this may be because in the words of one government agency, "Sea lampreys are like swimming noses." Indeed, their appearance — especially with mouth agape — looks like something out of a Guillermo Del Toro movie. At every stage in a lamprey's life cycle, they make life-or-death decisions based primarily on their sense of odor, from finding breeding grounds to navigating through large bodies of water. Lampreys generally survive by gorging off the blood of other fish species. In other words they are not, by today's standards, an appealing food source.

Yet according to medieval historians, King Henry I did not just occasionally indulge in lampreys. He enjoyed their beef-like flavor so much that he ate them regularly — to the point where, according to historians, he ate a "surfeit of lampreys" and it literally killed him.

"One chronicler (Henry of Huntingdon) wrote about Henry I's last meal of lampreys, which he was said to have eaten against medical advice," Dr. Judith A. Green, Professor of Medieval History at the University of Edinburgh, told Salon by email. She added that there is no any other written record of the king's culinary preferences — although when it comes to her own, she says: "I have never tried lampreys myself, but I taught at Queen's Belfast for many years, and lampreys were caught in Lough Neagh."

Dr. Edmund King, Professor Emeritus of Medieval History at the University of Sheffield, described Henry of Huntingdon as someone who "liked a good story" and noted that "there may be something in the lampreys story, since it comes from close to the time, and the chronicler was well connected." If nothing else, because King Henry I's body was eviscerated so his entrails could be buried in Rouen, it is plausible that chroniclers examined the contents of his stomach and noted the presence of lamprey parts.

"That the king was fond of lampreys is perfectly likely," King wrote to Salon. "Whether they killed him is another matter. A lot of fish was consumed in the middle ages, in part because of the prohibition of the eating of meat by the church at certain times."

Dr. Marc Gaden, Deputy Executive Secretary of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission and an expert on lampreys, told Salon that they were very popular as a food in medieval Europe. He also pointed out that lampreys are still somewhat popular, such as in France where they are considered a delicacy. Gaden explained that, despite their horrific appearance, there is nothing inherently harmful or dangerous about eating lamprey meat, and that if King Henry I did expire from eating too many lampreys, it was likely due to food poisoning related to how the lampreys were prepared rather than because of the lamprey flesh itself.

Ironically, though, there is a strong case to be made that lampreys should not be eaten in the modern era.

"Though you might have a taste for lamprey in Europe or in England, you can't get them. They're protected."

"It's an issue in Europe because lamprey are on the ropes there due habitat loss and dams, and all the things that block lamprey from reaching their spawning grounds," Gaden told Salon. "This has taken a huge toll on these native species. That is why, though you might have a taste for lamprey in Europe or in England or something, you can't get them. They're protected."

Indeed, the need to protect lampreys is so great that it has even caused an alteration of a venerable English tradition. When Queen Elizabeth II was due a lamprey pie to celebrate her jubilee, the restrictions compelled England to use eels instead.

"There is a quaint tradition that the city of Gloucester sends the Monarch a pie made out of lampreys that goes back to the Middle Ages," Gaden pointed out, noting ruefully that the tradition could not be safely continued with English lampreys.

Ironically, the North American Great Lakes region has the opposite problem with lampreys; there, they are an invasive species, killing off local fish populations that the nearby regions rely upon to survive. Even worse, many lampreys have been rendered unsafe to eat as a result of human environmental irresponsibility. There have been high concentrations of mercury found in lampreys from the Pacific to Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Regardless of whether King Henry I truly died from eating a surfeit of lampreys in 1135, it is likely stuffing his stomach with them would get him quite sick today.

That said, it would be unfair to King Henry I to let this article end with his unseemly demise. As Green pointed out, he also "reunited England and Normandy under one ruler, brought northern England more securely under the English crown's rule, was remembered for his strong rule over England, [and] had more acknowledged illegitimate children than any other English king." Diet aside, no one could accuse Henry of being uninteresting.