Michael Brown and Anthony Brown grew up together around a tough housing project in Bronzeville.

They weren’t related, but their families say the boys had a lot in common. By the time they hit high school, though, they had become “opps,” rival gang members, maybe more imagined than real but still deadly.

On Feb. 8, police say, Anthony got out of an Infiniti SUV he had just stolen and shot Michael at least 10 times while standing over his body on a snowy street about a mile from where they had played as boys. Michael was 15, Anthony 16.

The shooting once again confronted the city with kids killing kids and the problem of meting out justice to juveniles while keeping the streets safe.

Anthony had twice been arrested on gun charges last year but remained free on electronic monitoring. On the day of the murder, police say Anthony appeared before a judge in one of those cases, then ordered a Lyft and carjacked the driver, picking up a friend before targeting Michael as he walked home from the Chicago Military Academy.

Michael Toomin, the presiding judge of the Juvenile Justice Division, told the Chicago Sun-Times that a juvenile facing a second gun charge — like Anthony — should be locked up. He says it’s hard to disagree with those who feel juvenile offenders are given too many chances, even when considered a danger to the public.

“The state’s attorney’s office has been very lenient to these minors that have come in, in the last three years,” said Toomin, a veteran judge who once presided over criminal courts in Cook County. “They’ve made offers to the public defender from the beginning where the push was to get as many people out of detention who were up there awaiting a disposition or a trial.”

Andrea Lubelfeld, who’s in charge of those public defenders, said it’s not a matter of leniency but of finding better alternatives than jail for young teens like Anthony.

“Societies are safer when we address the issues that are affecting my clients, giving them what they are lacking and caring about them and giving them hope,” said Lubelfeld, whose office briefly represented Anthony in the murder case.

State’s Attorney Kim Foxx — who has been accused of being too lenient on gun crimes — told the Sun-Times that jail can make a juvenile more dangerous.

“I’m not saying that there’s not a role for incarceration of juveniles at all,” she said in response to Toomin’s comments. “What I am saying is we have to be thoughtful with how we engage it and how we use it, when we have a body of evidence that tells us for a lot of young people who come out of incarceration, they fare worse.”

The debate has sharpened as gun violence has hit record levels in Chicago, and more and more juveniles are being arrested for serious crimes. Families like those of Michael’s and Anthony’s are caught in the middle, at a loss when talking of justice.

“Everybody wants justice,” said Resheima Bailey, who describes herself as Michael’s second mom. “They caught him right away, so they’re like, we got justice. But did we really get justice? Because that’s another kid. That’s another kid, and I feel for that kid. He was just another boy living his life on the street the best way he knew how.”

Anthony’s mother said justice is the last thing she expects to see for her son, though she had sympathetic words for Michael’s family.

“I sympathize for my child. And like I said, my son is innocent,” Martavia Lambert said in an interview with the Sun-Times. “However, at the end of the day, someone else’s child is gone ... So I sympathize with that family as well.”

She fears police and prosecutors will not treat her son fairly and mentions her own experience when she was sentenced to prison for stabbing and killing Anthony’s father during an argument when Anthony was not yet 2.

“They lock up innocent people and charge them with murders just because they want to close cases, or they lock up people who actually did things to protect themselves,” Lambert said. “So it’s like there’s no right and no wrong when you have people who choose to play God.”

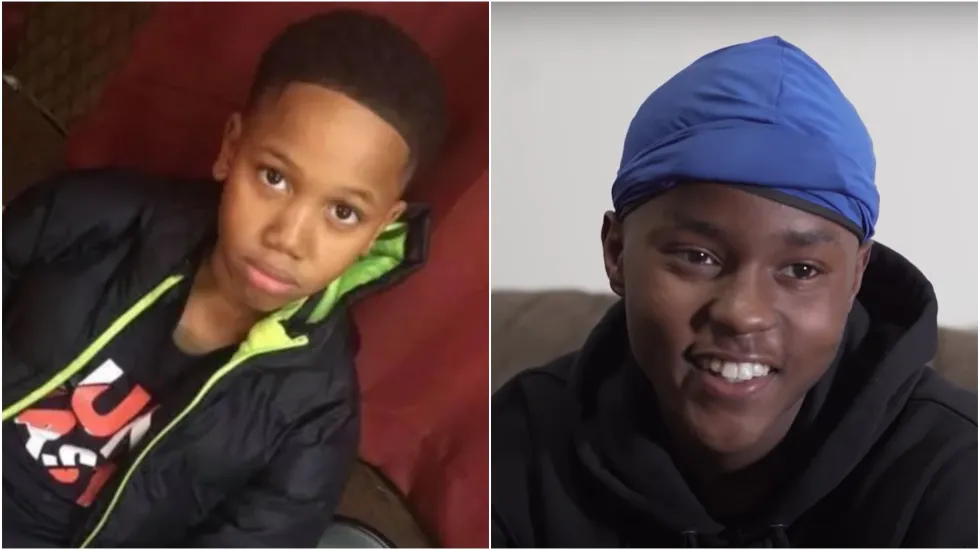

Michael

The oldest of three children, Michael Brown was a scrawny kid diagnosed with diabetes early in his life.

“Lil Mike was this fun, outgoing, smiling, facing challenges young man,” Bailey said. “Even with dealing with his diabetic issues, he still strived to be the best he can be ... He just loved playing basketball or playing a game or just spending time with his cousin and just being around family.”

His mom worked full time at a hospital while going to school and raising her kids in the Dearborn Homes, a housing project at the edge of Bronzeville. His father, whom Bailey described as a “street guy,” has been in and out of jail and is currently behind bars.

“You only have one parent in the home. She’s out working and trying to make sure you guys get a better life for you all. And my nephew was just basically out there raising himself and getting himself into trouble,” Bailey said. “There were a lot of older men in his life, but they’re teaching him the wrong stuff.”

Last year, Michael was sent to live with Bailey’s sister in Florida to “start a new life.”

“We got him to safe ground,” she said. “But my nephew, he was facing depression and anxiety ... He was good. My sister gave him a better life. He had his own room, he was in school, we bought him new clothes, we bought him new shoes, we bought him a phone, this, this and that. He wanted his mom.”

Eventually, his mother bought him a plane ticket home but enrolled him in the Chicago Military Academy in Bronzeville for “some type of structure,” Bailey said.

Michael liked to perform rap music, and Bailey hoped that would get him closer to his father, whom she described as a talented songwriter.

Bailey said their last conversation was about his 16th birthday, which would’ve been March 30. Michael asked his aunt for an outfit from Gucci to wear that day, but she had other concerns.

“I was telling him that I love him, and I was telling him that I want him to be a better person than what he is,” she said. “And I was telling him that I needed him more than he needed me.”

Michael aligned himself with a faction of a street gang that has long operated out of the Dearborn Homes, according to his aunt. At least one Instagram post shows Michael holding a handgun.

Bailey said her nephew was just posing, like a lot of kids his age. “That was like a whole complete other person,” she said. “From the internet world to real life ... it’s two different people.”

Bailey believes her nephew was killed as “revenge” for the fatal shooting of a 22-year-old rapper from Anthony’s gang exactly a year earlier. “These kids are dying every single day for senseless stuff,” she said. “You guys don’t have no reason to be arguing or having opps or even wanting to kill each other.

“All this stupid rah-rah stuff don’t matter because you’re gonna lose your life,” Bailey added. “And I used to tell him that all the time, I used to tell my nephew that all the time. You have to want better for yourself, you have to do better. You have to stop surrounding yourself around these know-nothings. But as a child living in poverty, you don’t have a choice.”

Bailey said she learned of her nephew’s death when her phone rang and his name popped up. “So I’m thinking it was my nephew. But when I pick up, the screams from his mom. I just knew what it was then.

“These kids actually grew up together,” she said. “They stay in the same neighborhood, they’ve been knowing each other since babies. They just grew up and went their separate ways and became what they call opps, or whatever. Just kids trying to do adult things. For what? I don’t know.”

Anthony

Anthony was three months shy of his second birthday when his mother fatally stabbed his father — also named Anthony Brown — during a fight at her grandmother’s West Side apartment in March 2007.

She was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 13 years in prison, despite her claims of self-defense. On appeal, Lambert argued the trial judge wrongfully excluded testimony that Brown had been violent during past fights, shattering her eardrum and breaking her leg.

During the fatal fight, Lambert said she had been hit with a fan, but the appellate court ruled the “use of a knife in this instance was absolutely unreasonable.”

In an interview posted to YouTube last October, Anthony talked about how that night changed the course of his life. “I think I wouldn’t be who I am now,” said Anthony, who has posted several well-received rap songs under the name of 757BabyGlock, a number that represents his renegade gang faction.

“I probably [would have] been in a different environment, living good, still in school, not a target, able to go everywhere,” he said.

His mother said her son was hoping his music would still get them to that better life.

“Anthony’s reason for rapping was to try to get his mom out the hood, change the life for his family,” she said. “He’s sick of poverty, he’s sick of everything that’s just been going on around and depression ... Depression is like one of the main things he been battling.

“I’m not just saying this because he’s my child, but he is so fun, he is so different, people don’t understand him,” she continued. “He’s been dealing with a lot.”

Anthony had been following a model that worked for some local drill rappers who have achieved international fame, like Chief Keef and G Herbo. In his music videos — some of them getting more than 100,000 views — Anthony is seen toting high-powered weapons and reciting menacing lyrics.

Four days before the shooting, Anthony released a new song on YouTube. “I’m itching, I’m itching, I’m itching for a body,” he raps in the chorus. “I’m itching, I’m itching, I’m itching for a robbery.”

The song was released around the year anniversary of the slaying of 22-year-old Keonte Molette, Anthony’s friend who used the rap name 757 Gunsmoke. Members of the gang Michael was aligned with had mocked Molette’s death and appeared to claim responsibility on social media.

Prosecutors have given no reason why they think Anthony killed Michael. Their case against the teen, so far, involves evidence gathered from video and from his electronic monitoring bracelet that tracked his movements that day.

At 2:15 p.m., Anthony allegedly put a gun to a Lyft driver’s head and carjacked him. Fifteen minutes later, he picked up a friend, prosecutors say. At 3:15 p.m. Anthony allegedly spotted Michael, jumped out of the car and fired at least 10 times.

He and the friend were pulled over less than half an hour later by police who had tracked down the license plate of the stolen SUV. A gun was found in the car, and prosecutors say Anthony was wearing the same clothing as the shooter, a sweatshirt with the words, “Reach for the Stars.”

Following Michael’s killing, Lambert posted on her son’s YouTube page: “I love you so very much son.”

Lambert said her son has been harassed while being held at Cook County’s Juvenile Temporary Detention Center. She said she has also received death threats targeting them both. Despite the considerable evidence against her son, Lambert said she keeps herself focused on a path forward, a better life.

“When I do get my child out, we already discussed the next moves to make,” she said. “What to do, who not to associate with and what to do as far as what’s going to better him as a person.”

Justice

Michael’s killing has once again shone a harsh spotlight on Cook County’s juvenile justice system, which has its beginnings in 1899 when the country’s first court for minors was set up here.

It is designed to be less adversarial and punitive than the traditional justice system. But critics say it has become too lenient, and they point to Michael’s killing.

When a child 17 or younger is arrested, they can be placed into a diversion program that keeps them out of court. Or they can be offered a “deferred prosecution agreement” that refers them to social services. Their cases are dismissed if they complete a mandated program.

In 2020, Gov. J.B. Pritzker announced a four-year plan to place juveniles in a setting more collegiate than institutional, with a focus on rehabilitation. Pritzker cited data showing that, from 2010 to 2018, 55% of those released by the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice ended up back in the system.

But more and more juveniles are entering Cook County’s juvenile justice system, straining resources designed to keep them out of jail. Toomin, who supervises judges in the Juvenile Justice Division, said many kids who appear before his judges have several arrests in their background.

Last year, charges were filed against juveniles in about 50% of all cases brought by police, according to data provided by the state’s attorney’s office. That’s up from 39% in 2020 and 34% in 2019.

When looking at just serious crimes, the rates were even higher: 85% of felony charges sought against juveniles were approved, up from 64% in 2020 and 59% in 2019.

Should a case go to trial, a judge can sentence a child to supervision or probation, or to be placed into the custody of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services or a juvenile detention center.

Of all the juvenile cases presented to prosecutors last year, 10% were offered a diversion.

For kids who are 16 and 17 — Anthony’s age — their cases are automatically transferred to adult court if they are charged with first-degree murder, aggravated sexual assault or aggravated battery with a firearm, if they are also accused of pulling the trigger. But children as young as 13 can be charged as adults at the discretion of prosecutors.

The state’s attorney’s office could not provide information on how many juveniles are currently facing charges as adults. The office of the chief judge also could not supply those figures.

Anthony was well acquainted with the juvenile justice system by the time he was charged with murder as an adult.

He was charged with unlawful use of a weapon last June when he was found with a .22-caliber Glock handgun after a foot chase, prosecutors said. He was released on electronic monitoring less than a week later, although the order was dropped later that month and replaced with a curfew order.

In December, he was arrested again and hit with a second weapons charge when he ran from a stolen car and was found with another handgun, prosecutors said. He was placed back on electronic monitoring in January — and he was still wearing that bracelet the day he was arrested for Michael’s murder.

Toomin believes some kids must be made more accountable for what they do.

“That’s something we could pay more attention to,” he said in an interview in his office. “If you’re just getting a pass and sent home ... it doesn’t mean anything to you.”

Toomin said he was surprised when he looked at his office’s data recently and saw only one juvenile had been transferred to a state detention facility in January, and none had been transferred in February.

“In other days, in other eras, there was no hesitancy … to lock somebody up,” he said.

Under the 1987 Juvenile Court Act, the need to protect the community must be weighed against imposing the least restrictive conditions on juveniles. Toomin said he believes recent efforts to keep juveniles out of detention facilities have gone too far.

“I think we’re in a mode where the pendulum swings and ... it’s swung in favor of crime,” Toomin said. “It’s going to swing back. I think you’re seeing that now.”

But State’s Attorney Foxx said she didn’t know what information Toomin was using to make such an assessment, and noted the decision on whether to lock up a juvenile, and under what conditions, are ultimately up to the judge in the case.

“The notion that somehow the state’s attorney’s office is the only participant in these proceedings is contrary to how the system works,” Foxx said. “A judge has every opportunity to object.”

Lubelfeld, who heads the juvenile justice division of the Cook County public defender’s office, emphasized the juvenile justice system is filled with kids with traumatic backgrounds, many of them living in “survival mode.”

“These kids are trying to raise themselves. And they’re children,” she said. “They’re making impulsive decisions, [and] they’re listening to older kids who aren’t the best mentors.”

Lubelfeld noted the brain’s frontal cortex doesn’t fully develop until about age 25, meaning children and teens are more prone to reckless behavior and decisions. Trauma also affects kids’ fight or flight response, rewiring the brain to overcompensate for potential danger.

“Their trigger is ready to go,” she said.

While juvenile offenders are offered resources through the courts — like mentoring, job training, and mental health and drug treatment services — Lubelfeld warned that social service agencies have been “cut to the bone.”

She called for deeper investments in communities to address some of those needs, as well as in schools and recreational services.

“It may make you feel good in the moment to say, ‘Oh, we should just lock these kids up,’” she said. “But in reality ... they’re going to come out worse, and they’re going to make the public even less safe.”

Madeline Kenney was a Sun-Times staff reporter when she worked on this story. She now works for the Bay Area News Group. Tom Schuba and Matthew Hendrickson are Sun-Times staff reporters.