Toronto parent Tessa Yang is raising Elia, who is best described as a gender-fluid child. (Pseudonyms have been used for both to protect their privacy.) Gender identity is something they discussed together when Elia was six. “When I asked, ‘Do you feel like a boy or girl?’ Elia said, ‘I feel 25 percent like a boy and the rest is like a kid.’”

Elia, now a teenager, used the pronouns “they/them” before switching to “he/him” in public school. A few years ago, she also started using “she/her,” and Yang seamlessly changes between the two sets of pronouns throughout our interview. “When Elia said to me, ‘I use she and he pronouns now,’ I asked, ‘How do you know which one to use?’ . . . but Elia just really wanted both all the time.”

Yang says that, when switching between pronouns, it’s like they’re “seeing a little more of Elia.”

When Elia’s voice first dropped, Yang considered visiting their family doctor to discuss puberty and puberty blockers, the medications used to postpone some effects of adolescence—like menstruation and voice changes—in children. After carefully broaching the topic with Elia, her response was that of a typical teen. “I didn’t say, ‘Do you want puberty blockers?’” says Yang. “I just named puberty and asked how he felt about that, and he was like, ‘Ugh, cringe.’”

Yang left it at that but made it clear to Elia that they could always return to the topic—though it has crossed their mind that the appropriate care might not be easy for Elia to access when and if he needs it.

New data from the University of California, Los Angeles, has found that the number of young people in the United States who identify as trans has doubled in recent years, which might help explain why access to gender-affirming care for children and youth has become the centre of an increasingly high-stakes public debate. Between 2021 and 2022, thirty-four US states introduced bills banning this type of care, with some labelling treatments like puberty blockers and hormone therapies as “child abuse.” While Canada may be more progressive on the matter, finding health care providers who are both willing and competent to provide these services to youths is still a serious struggle. In Ontario, any family doctor or nurse practitioner is legally allowed to refer patients for gender-affirming surgery, but in practice, there are few clinics that actually offer it. At Toronto’s SickKids Transgender Youth Clinic—one of the only clinics in the province that specialize in gender-affirming care for children—wait times to see a practitioner average one year.

The problem goes beyond a simple lack of service availability. At its core, it boils down to a misunderstanding about the nature of gender itself. On the conservative side, gender is determined by biological sex; on the progressive side, it’s often seen as internal—a feeling of strong identification with a gender regardless of the one assigned at birth. And while each side has its disagreements, there is a common denominator between the two views: permanence, or the idea that individuals have a single true gender identity. Parents and professionals alike worry about the perceived risk of making the wrong choice—that young trans people may eventually think they were mistaken about their gender identities and come to rue the day they were prescribed body-altering hormonal and surgical treatments.

Yet in the trenches of trans health care, there is a growing idea that pushes back against the “one true gender for each individual” framing altogether—one that could allow us to resolve the bitterly divisive culture war over the psychological and medical care of transgender children. What if, instead of viewing gender as a fixed trait, we started to think of it as something that could evolve over the course of a lifetime? Or if detransitioning wasn’t considered a sign of failure and was instead regarded as a natural and healthy part of the gender development process?

To access gender-affirming care, patients are often required to undergo a series of assessments. These vary across jurisdictions but can include simple psycho-social interviews with primary care providers, years of gender-focused psychotherapy, or a “real life test” in which the patient lives in their so-called “target gender” without access to medical treatment for a period of time. For bioethicist Florence Ashley, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law and the Joint Centre for Bioethics who has published widely on gender-affirming care for trans people, such procedures can cause more harm. That’s because there’s no reliable way to ascertain whether a trans person is “really” trans or not.

“The very idea of assessing gender comes from the history of devaluing of trans identities,” says Ashley, who argues that there isn’t any research to prove such assessments do what they promise to do: predict the future. “What we see from trans people is that gatekeeping makes them less likely to express doubts, which can impair their ability to make the best possible decisions.”

Ambivalence, of course, is a normal part of any decision-making process, particularly when those decisions involve potentially life-altering effects. As a transgender woman and former mental health clinician and therapist who spent several years working in the public sector with transgender children and their families, I’ve had countless conversations about gender with young people, parents, and professionals. I would often tell them that embarking on a gender transition is no different from any other major life decision, such as engaging in a serious romantic relationship, moving to a different country, or buying real estate. There will likely be benefits but also potential regrets—as well as the possibility that one might change one’s mind at any point in the process and seek a new direction.

Why, then, is gender transition still seen as an all-or-nothing process?

Over the years, many of the youth I saw expressed a deep terror and shame about the possibility of “getting it wrong,” while parents of trans youth often privately confided in me that they are afraid of their children getting “stuck in between” conventional gender expressions and never fitting into society. Yet most trans people already feel that way before transition.

Psychotherapist LeeAndra Miller has worked in LGBTQ2+ mental health care for over twenty-five years and is the project manager of Families in TRANSition at Central Toronto Youth Services, a virtual, nationwide program that provides psycho-educational support to hundreds of parents whose children have recently come out as transgender. (I helped develop the program’s curriculum while working there between January 2020 and October 2021, and I returned there part time last June.) They push back against the traditional notion that gender is a fixed trait, with gender transition being a linear and permanent shift from one gender to another.

“That’s the transphobic nature of this kind of thinking—that there’s one journey, one path, and that’s everything. That’s just not the reality,” says Miller. “We never know what anything is going to be like until we do it, and that’s a part of the discovery of who we are.”

Miller instead defines gender as a developmental process. “The variety of gender is as rich as the multitude of plants in the plant world,” they add. In Miller’s paradigm, gender cannot be reduced to biology, psychology, or social roles but is rather the way that an individual responds to all of these factors over time. From this perspective, trans people aren’t really so different from non-trans people: we all explore and develop our gender identities as we grow from childhood into adulthood, but some people experience bigger and more visible changes than others.

In the daily lives of transgender youth and the adults who care for them, such a shift in perspective might relieve the stress of having to commit to a single path. This model offers the chance to explore oneself fully without the pressure to make the “right” life-altering choice in a single moment. Instead, youth get to develop confidence in their own decision making through trial and error.

What I find most powerful about this approach is that it encourages deep trust and collaboration between young people and their caregivers. When adults take on a gatekeeping role, they may actually jeopardize their relationships. Telling youth that they’re wrong about their gender runs the risk of making them feel like they need to dig their heels in and cling even more tightly to their asserted identity. Yet when we trust in their ability to explore and decide for themselves, they’re more likely to reciprocate that trust by telling us if they feel confused or worried. In turn, this allows us to support them when, and if, they switch paths.

Of course, some parents and professionals might say that exploration is all well and good but what about the impacts of trying on a trans identity and then changing one’s mind? Or the potentially permanent effects of hormones and surgeries?

While a recent study published in the journal Pediatrics found that 94 percent of children who transition retain their gender identity five years after first coming out, Kinnon MacKinnon, an assistant professor of social work at York University, is undertaking research on the experiences of “detransitioners” and “retransitioners”— individuals who identified as transgender for a period of time and then returned to their previous gender identities (or, in some cases, moved into non-binary or gender-fluid identities). As part of a qualitative study published in 2022, MacKinnon interviewed twenty-eight adults on their detransitioning experience and found that the majority did not express feelings of regret—even when serious medical interventions were involved. “Most of those who went back to their assigned sex were still happy with having had some changes through medical transition—like orchiectomy (removal of the testes) or vaginoplasty (surgical construction of a vagina),” says MacKinnon. “They still felt content with their bodies and explicitly spoke against the narrative that they were regretful.”

He is careful to add that a small number did express regret. “Medical science stigmatizes changing your mind,” says MacKinnon, and that stigmatization, which contributes to the negative messaging from “gender-critical” or anti-trans organizations, may be partially responsible for those feelings.

MacKinnon has deep respect for the perspectives of his participants who detransitioned. “I felt like I was talking to people from the future,” he says. “They definitely went against the popular notions that there is an internal gender that we need to discover or authenticate. They spoke against the self-actualizing narrative, never felt like they had a true gender, but still experienced gender dysphoria and were seeking to alleviate that through medical transition.”

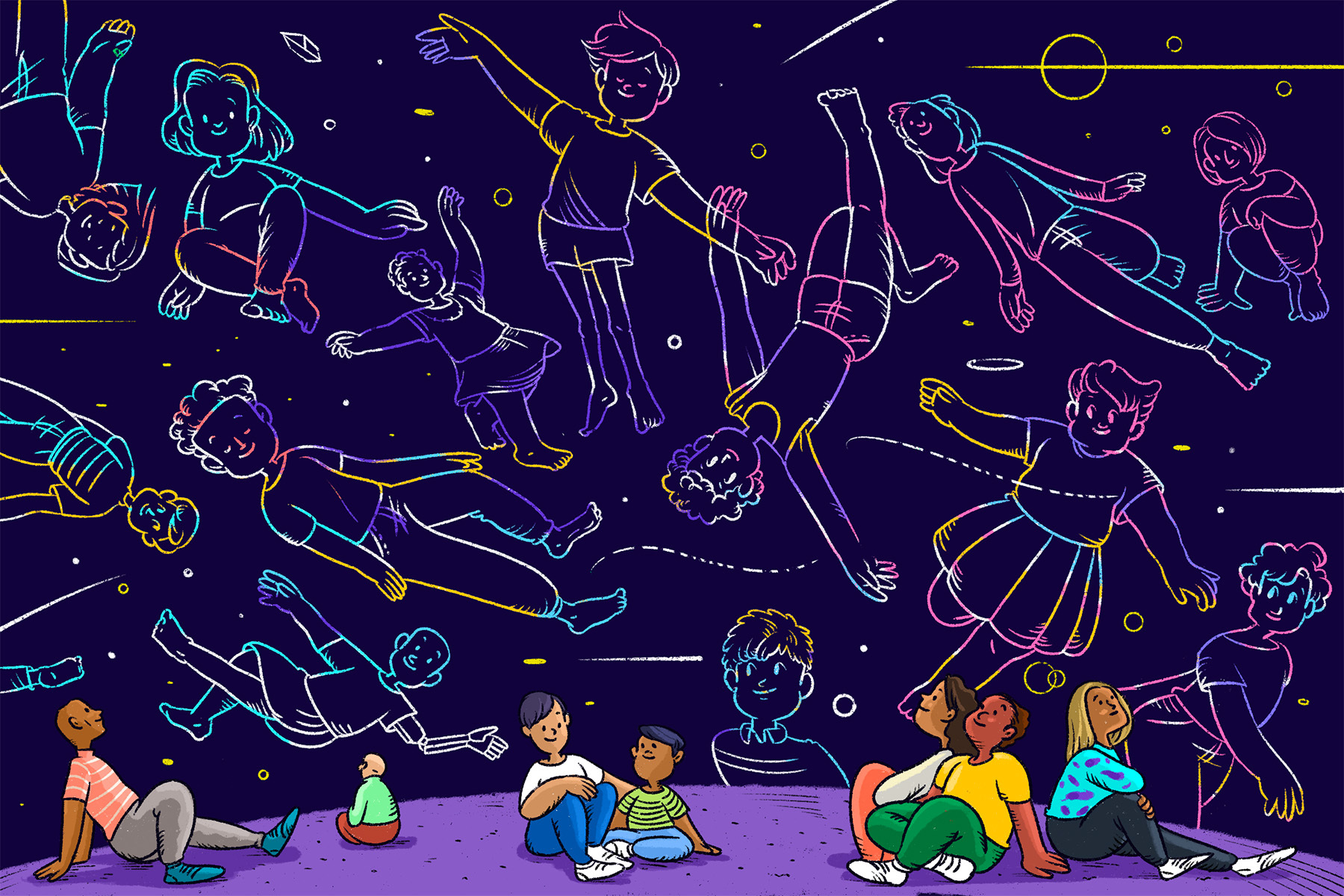

Perhaps this is what the new gender universe is all about: letting go of the illusion that we can be completely sure of anything, releasing the idea of certainty in order to embrace the complex truth of being alive, messy, complicated. “Gender is forever changing,” Miller says. “I think the galaxy is a great metaphor for it, because there’s tons we don’t know—and that’s great if we have the courage to step into it.”

As for parents? We might need to shed the idea of providing children with easy futures so that we can instead offer them deep attunement and care in the present. And while parents certainly have a role to play in guiding gender-diverse young people’s decisions, it may ultimately be best to follow their lead.

Tessa Yang tells me they worry about how their parenting choices may be interpreted by people around them. “I’ve been accused of teaching my child what to be,” Yang says. “I am teaching my child, but I didn’t teach my child who to be. It was to make sure my kid knew they were loved and accepted by me—that I wanted to see them and whatever they are and celebrate it.”