The vast expanse of internet connectivity, online media, social media platforms, gaming platforms, and new forms and uses of artificial intelligence (AI) have opened enormous opportunities for commerce and communication.

The sheer convenience and ubiquity of online connectivity have made the internet a new way of life for nearly everyone in the 21st century. This is especially the case for children, whose social lives have almost entirely migrated online.

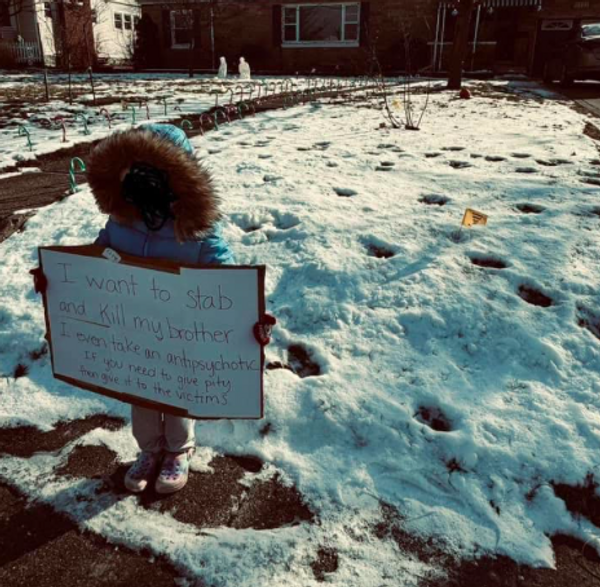

As my research on digital childhoods demonstrates, this realm of online communication has also created disturbing opportunities for harms to children.

These harms have concerned politicians, with the government announcing a plan to impose a minimum age for children accessing social media and gaming platforms.

As digital natives, children are part of the solution. In a discussion dominated by adults, my research looks at what kids think about the harms they experience and how to prevent them.

New forms of harm

The explosive emergence and multiplication of online harms poses serious threats to the safety and wellbeing of children. Harms facilitated by generative AI are just one example.

In a study I conducted involving participants in Australia and in the United Kingdom and in-depth interviews on the experiences of 42 children in the UK, children reported they were experiencing:

cyberbullying

unwanted contact

unwanted content

grooming

exploitation.

Some young people say the harm caused by deepfakes, eating disorder videos, sextortion, child sexual exploitation material, misogynistic content, scams and other forms of online harm are having long-lasting effects on their mental health.

We need to keep holding AI and tech developers, companies and social media owners to account. These are commercial services and companies – ultimately, people are making a profit while children are experiencing harm.

For instance, Harvard Medical School’s study estimates social media companies are making billions of dollars from US children’s use of online platforms.

A recent global report from Human Rights Watch exposed serious violations of the privacy of children. Australian children’s images, names, locations and ages were being harvested and used without permission to train artificial intelligence (AI) models.

The report’s author urged the federal government to “urgently adopt laws to protect children’s data from AI-fuelled misuse”.

Regulatory catchup

In June 2024, Australia’s attorney-general introduced a bill in parliament to create new criminal offences to ban the sharing of non-consensual deepfake sexually explicit material. In relation to children, this would continue to be treated as child abuse material under the criminal code.

A Senate committee released its report on the bill last month. It recommended the bill pass, subject to recommendations. One recommendation was “that the Education Ministers Meeting continues to progress their work to strengthen respectful relationships in schools”.

The federal government’s approach has been critiqued by Human Rights Watch. It argues it “misses the deeper problem that children’s personal data remains unprotected from misuse, including the non-consensual manipulation of real children’s likenesses into any kind of deepfake”.

We are still awaiting reforms to the Privacy Act and the development of the first Children’s Online Privacy Code.

What can we do to help?

While these wheels of reform turn slowly, we need to urgently continue to work together to come up with solutions. Evidenced-based media reporting, campaigns and educational programs play key roles.

Children and young people say they want to be part of developing the solution to tackling online harms. They already do important work supporting and educating their peers. I refer to this as “digital siblingship”.

My research calls for greater recognition of young people for the role they play in protecting, promoting, and encouraging other children to know their rights online.

Children want the adults, governments and tech companies to swiftly act to prevent and address harms online.

However, a lot of parents, guardians, carers and grandparents report feeling a step behind on technology. This means they can feel at a loss to know what to do to protect, but also empower, the children in their lives.

Adults should talk with children about online safety often, not just when something’s gone wrong. These discussions should not lay blame, but open communication and create safe boundaries together.

Children feel better education and training for their peer group and for the adults in their lives is essential.

In the classroom, children suggest peer-led training on online safety would be more effective. They want other young people to educate, train and support them in learning about and navigating online platforms.

But education should not just be happening in schools. It needs to extend well beyond the classroom.

Policymakers, educators, regulators and the mainstream media need to commit to equipping all Australians with the most up to date information, knowledge and education on these issues. The companies need to comply with the law, regulations, standards and commit to being more transparent.

In an era where digital landscapes shape childhood experiences, safeguarding children from online harms requires a collective commitment to strategies which promote vigilance, education, and proactive regulation. We must ensure children are empowered to thrive in a secure and supportive online environment.

Faith Gordon currently receives funding from The Australian Research Council. Faith Gordon has also received funding from the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration, The Social Switch Project in the UK and was an academic consultant for one project with Encorys in the UK.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.