Kenyan Muslims played a part in the push to repeal repressive political laws in the country in the early 1990s. But Muslims, who account for 11% of the population, have yet to enjoy the fruits of their activist labour.

This is because they remain divided. Their division – due both to internal and external factors – means they aren’t a political power bloc big enough for the elites who run the country to seek their support as a community. In Kenya, political and economic power rests with the large ethnic groups.

There have been attempts before to organise Kenya’s Muslims, but these have failed. One reason is opposition by the country’s political leadership to using religion as the basis for political mobilisation. Leaders fear that mobilisation along religious lines risks being abused by extremists who seek to impose an Islamic state governed by sharia.

Yet, Islam in Kenya has become increasingly politicised. As I have argued before, this process, beginning in the early 1990s, can be traced to the policies of post-independence regimes that have left the Muslim minority behind.

Muslims have felt increasingly marginalised economically and politically in Kenya. The majority of Muslims are jobless, low-income earners, and generally poor. This is not to suggest that Muslims are economically worse off than other minority groups in Kenya. But regions dominated by Muslims record a high percentage of the population in poverty and illiteracy.

Furthermore, in the global war on terror, Kenya’s pursuit of violent extremists has led to increasing human rights violations while intensifying historical frictions between the state and the Muslim community.

Unlike previous terrorist threats, such as the embassy bombing in 1998, attacks by the Somali terrorist group Al-Shabaab and its Kenyan supporters such as Jeshi Ayman have targeted the country’s institutions. The upshot is a backlash by the state against its Muslim population. There have been targeted kidnappings and extrajudicial killings. The backlash bolsters the narrative of government mistreatment of the community.

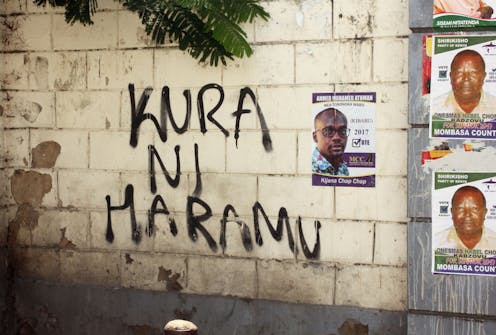

In an election year, this could be used as a rallying call to mobilise Muslims to vote in a certain way. However, there is no common Muslim position on which of the two main coalitions to support. This can be traced to age-old ethnic and racial rivalries within the Muslim community.

These disputes extend beyond internal religious rivalries. They have implications for how the state relates to the community.

Internal rivalry and elusive unity

Divisions among Muslims are numerous. There is a small but relatively wealthy minority of Arab and Asian descended Muslims. Then there are coastal and up-country Muslims. Coastal Muslims are mainly descendants of the local communities that first adopted Islam no later than 500 years ago. By the 16th century there were several Muslim communities dotted along the Kenya coast.

The so-called upcountry Muslims are considered more recent converts – from around the mid-20th century. Coastal Muslims tend to question the “Muslimness” of upcountry Muslims.

The government capitalises on these divisions. When the Islamic Party of Kenya began to gain influence in the early 1990s, government sponsored the United Muslim of Africa party as a counter. The new party, founded and supported by African Muslims, became critical of the so-called Arab Muslims, stressing its African identity before Islamic solidarity.

During the colonial period, the British administration had varied policies towards different groups of Muslims in Kenya. Arab Muslims were higher up in the pecking order. Indigenous Muslims were classed together with other Africans at the bottom of the racial hierarchy. The colonial legacy of this divide between Muslims lives on today in ethnic and racial rivalries and divergent aspirations.

In the years leading up to Kenya’s independence in 1963, some Muslims at the coast and the northern region of Kenya wanted secession. The secession agenda was driven by the fear of Muslim marginalisation in a postcolonial state presided over by Christian politicians. At the coast, they sought to form a separate state or reunite with Zanzibar under the leadership of the sultan. In northern Kenya they sought to be part of the larger Pan Somalia state.

The Mwambao movement that championed the secession agenda at the coast attracted minimal support. It was seen as an effort by Arabs to retain their political and economic dominance. Pwani (the coast) became part of Kenya.

In the northern region, though the secession movement was popular among the Somalis, the minority communities were reluctant to support this agenda, fearing Somali political ascendancy.

Consequently, in postcolonial Kenya, Muslims have been viewed as “foreigners” because of their history of seeking separation.

The political aspirations of a separate state for the coastal community re-emerged in the 1990s. Under the rallying call “Pwani si Kenya” (the coast is not part of Kenya), the outlawed Mombasa Republican Council argued that the former Coast Province had never been part of Kenya and had a legal right to a separate status.

Unlike the Mwambao, the new movement was secular and attracted supporters across different religions. After about 10 years it fizzled out. Government cracked down against its leadership and most coastal residents were put off by the movement’s support for violence.

Due to this history of fissures, there have been disputes about who has the right to speak for Muslims in Kenya. These find expression over pronouncements about the sighting of the new moon to mark the beginning and ending of fasting during the month of Ramadan.

The war on terror and extrajudicial killings

A growing population of unemployed Muslim youth is easily attracted to radical preachers who allege systematic discrimination of Muslims by the state. Many have been recruited to join Somalia-based Al-Shabaab, which was responsible for at least 409 attacks on Kenya between 2005 and 2017.

The government response to the terrorist attacks and increased radicalisation has heightened feelings of marginalisation and discrimination. Between 2012 and 2014, more than 10 radical Muslim clerics were assassinated by security agents.

At the core of recent Muslim political activism against the state are those influenced by the Saudi-Wahhabi interpretation of Islam. Its leadership condemns collaboration with the state.

The appearance of numerous factions within the community is an indication that narrower interests have always succeeded over larger abstract goals, such as that of Muslim unity in the country. Arguably, the country’s Muslims have made their marginalisation a reality because of their failure to achieve unity.

Hassan Juma Ndzovu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.