There is active evil, and there is the passive kind. Separating our self-identity from the first is easy for Americans to do. Nobody wants to be called a Nazi, a Klansman, or an antisemite, and the average American decries acts of overtly racist violence and brazenly authoritarian philosophies.

Passive evil, however, is far more insidious and dangerous because it spreads easily. When governments put resources behind it, it emboldens neighbors into becoming bullies and, if taken far enough, murderers. This is one of the urgent themes threading through Ken Burns' latest opus, "The U.S. and the Holocaust," a six-hour examination of the ways that the United States' neutrality during Adolph Hitler's psychopathic rampage across Europe contributed to the mass murder of six million European Jews.

It's also a warning, delivered through the accounts of Holocaust survivors and others who escaped the Nazis, and the unearthed writings of those who perished.

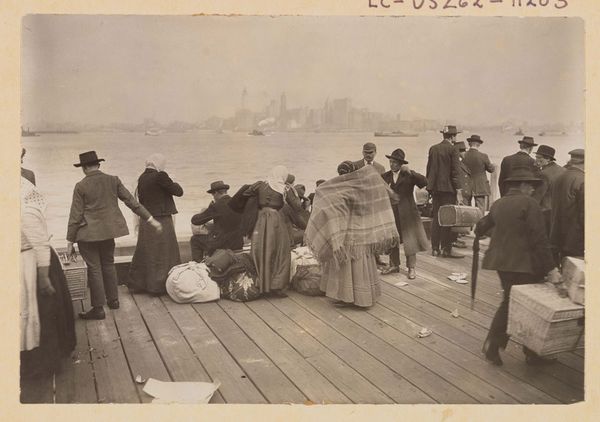

To those familiar with Burns' filmography this title, "The U.S. and the Holocaust," may read as a supplement to his 2007 opus covering World War II. In reality, it's something of a sequel to 1985's "The Statue of Liberty." The three parts of this work, each deriving its title from phrases from Emma Lazarus' "The New Colossus," remind us that we have yet to live up to the ideals that American icon and New York's Ellis Island symbolize.

Burns is known for exploring and celebrating the American story – our heroism, ingenuity, and goodness – and the Second World War's dominance in that mythology is as powerful as ever.

Many of the less savory parts of that narrative have been glossed over to our detriment and peril – enough to create recognizable parallels in the political and social sentiments dominating early 20th century America and Europe and the times in which we're living. Nativist populism was on the rise, as it is now. Nearly a century ago, it was left unchecked, and Hitler and Nazi Germany accelerated it to genocidal ends.

Anyone tuning in for another unscripted celebration of G.I. bravery, national sacrifice, and red-white-and-blue gumption is in for a shock.

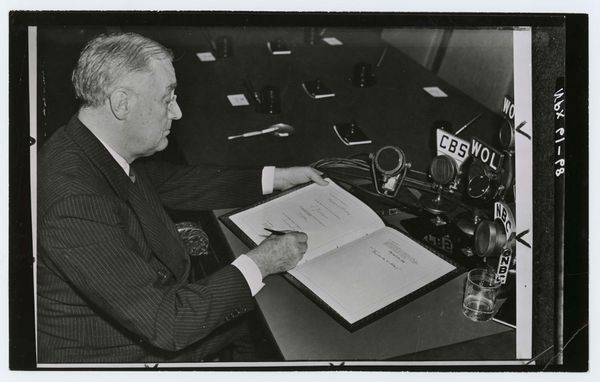

But as Burns and his co-producers Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein spell out in this three-part film, our hesitancy to join the fight was not accidental, and the mollifying trope that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt didn't know what was happening simply wasn't true.

Rather, it was rampant antisemitism and anti-immigration sentiment that delayed the United States' entry into World War II. Politicians worked to curb European Jewish resettlement in the U.S. A pastor preached his gospel of antisemitic lies and conspiracies on one of the most popular radio shows in the nation.

Roosevelt may have been the first major presidential candidate to denounce antisemitism in 1932, appointing more Jews to his administration than any of his predecessors. But he was loath to risk alienating the public by committing our troops to the war until Germany and Japan forced his hand.

Therefore, anyone tuning in for another unscripted celebration of G.I. bravery, national sacrifice, and red-white-and-blue gumption is in for a shock. "The U.S. and The Holocaust," which is narrated by Peter Coyote and features the voices of Liam Neeson, Meryl Streep, Matthew Rhys, Paul Giamatti, Werner Herzog, and others, does nothing to blemish our veterans' hard-won pride and honor.

Rather, it imposes a clarifying honesty on our claims of openness and exceptionalism. For a time, Americans were proud to fight a war against fascism. When it came to fighting a war to save the victims of fascism, we would have preferred to stay neutral.

Think of "The U.S. and The Holocaust" as Burns, Novick and Botstein's way of affirming our righteous role in the war while also helping us to understand the heavy toll xenophobia takes on our humanity. Most of the Holocaust's victims were dead before American soldiers set foot in Europe, one of its experts points out.

When the United States finally entered the war, as one of the many historians consulted for the documentary points out, the war department didn't want American soldiers to know about the mass extermination of Europe's Jewish population. They were afraid that our G.I.s wouldn't fight as hard if they thought they were fighting for Jews.

But this veers away from what makes "The U.S. and the Holocaust" required viewing, which is its determined focus on the everyday people living in cities across Europe before the Nazis mass murdered.

Where most documentaries about this war or the Holocaust take a tight focus on the war machine or the ways Hitler and his general mass murdered civilians, Burns, Novick and Botstein drill down on how common and ordinary life was for these families before the Nazis came to power.

Günther Stern, the only member of his family who was able to flee to the United States before the Nazis changed their policy from deportation to extermination, remembers looking out of his apartment's window to see his classmates marching in a parade for the SS. Eva Schloss, who survived a death camp, recalls realizing on Kristallnacht that the people throwing stones and bricks at the windows of her family's home were her neighbors.

But the voices of those who didn't make it, are heartwrenching. "My dear ones," reads a note written by a Polish woman and dated June 16, 1942, "I am writing this letter before my death. . . . My hand trembles, and it's hard for me to finish writing. Farewell." She then signs off in the name of her family, including the youngest – a toddler "who doesn't understand anything yet."

Many have pointed out the similarities between Hitler's rise to power and that of Donald Trump and the MAGA movement. The two-hour opener makes this plain through the mere description of how the Nazi party's numbers ballooned, enabling Hitler to take power.

His followers downplayed the most objectionable aspect of their platform, their antisemitism, to appeal to moderates. Meanwhile, they stepped up their street warfare on groups deemed unpatriotic to convince voters that civil war was imminent.

Burns likes to remind journalists that history doesn't repeat. It echoes.

A small group of elite conservatives saw to it that Hitler became chancellor, confident that the weight of office would calm his extreme temperament – another way of claiming confidence that he'd act more "presidential."

The producers did not create "The U.S. and the Holocaust" to be a veiled indictment of Trumpism, Republicans or the MAGA movement. They said as much at a recent Television Critics Association press conference for the documentary, which they began producing in 2015 – before Trump became president.

Back then, Botstein said, "it was impossible to imagine where we would be, not only here in America, but across the ocean and around the world." Burns likes to remind journalists that history doesn't repeat, it echoes through the decades and in current events for the simple fact that humanity doesn't change all that much.

This is why the right-wing's xenophobia, recently on display in Florida's Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis' inhumane stunt of flying migrants from Texas to Martha's Vineyard under false pretenses, isn't original. They echo efforts made by racists in Roosevelt's government to restrict immigration or bury emergency measures to help European Jews.

World War II's popularity and dominance in the American story should help "The U.S. and the Holocaust" draw a significant viewership, or at least one hopes that's the case. One of the concerns raised by author Daniel Mendelsohn, whose family's story is featured in all three segments, is that the memory of the horrific crimes against these six million Jews and hundreds of thousands of others is receding into memory.

He's right. The internationally hailed writings of Anne Frank feature prominently in the third installment, and hearing her optimism in the face of death is fortifying. Mendelsohn also reminded the journalists covering that press conference that Frank's face was used in a meme posted to the Facebook page for a Rhode Island sports bar during one of this summer's heatwaves. It read, "It's hotter than an oven out there . . . And I should know!" (When a radio host contacted the owner to ask why he did it, he only said that he thought it was funny.)

Mendelsohn went on to say that he doesn't believe the bar's owner thinks of himself as an antisemite . . . but this is a classic example of passive evil. "There's no bottom, as one of my survivors said, to the things people will do to one another," Mendelsohn says in the documentary. "The structures of what we think of as our civilized lives, they fall apart very easily. Surprisingly easily."

How does that happen? He references the citizens who reported on their Jewish neighbors or committed violence against them directly after living beside them for years.

Waiters, people at the dry cleaners, the woman at the restaurant, "that's who these people were," he says. "Don't kid yourself."

"The U.S. and the Holocaust" premieres at Sunday, Sept. 18 at 8 p.m. — is off Monday — and continues with Episode 2 on Tuesday, Sept. 20 and Episode 3 on Wednesday, Sept. 21 on PBS member stations, PBS.org and the PBS Video app.