The four emergency room visits, emotional turmoil, possibility of infertility and her foetus’ fatal diagnosis were not enough for Texas to allow Kate Cox to get an abortion, illuminating a major issue with the state’s strict abortion ban: ambiguous language that undermines exceptions to the law.

On Monday, the state’s ultra-conservative supreme court reversed a lower court’s emergency order initially granting Ms Cox an abortion. The court claimed she did not meet the state’s requirement to have an abortion but noted that it was up to a physician to determine when an abortion was warranted, not a court.

The ruling directly contradicted what the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) and Ms Cox’s doctor argued about the urgency of her case. It also provided little clarity on the state’s interpretation of the law.

Ultimately, Ms Cox couldn’t wait for the court to decide the fate of her body. Her condition was so dire that she ended up fleeing Texas to seek care.

Though the case may be the first of its kind to make national headlines, experts say it is far from the last if states continue to enact strict anti-abortion bans using vague language.

A once far-fetched situation becomes a reality

The “hellish” situation Ms Cox was put in this past week is a tangible example of the extreme lengths anti-abortion lawmakers will go to attack abortion rights – something activists have warned about since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade last year.

For weeks leading up to the Texas Supreme Court’s decision, Ms Cox, 31, suffered painful cramping, diarrhea and unexplained leaking fluid – symptoms associated with her third pregnancy’s diagnosis: trisomy 18.

Trisomy 18 is a life-threatening chromosomal disorder that most often results in a miscarriage or stillbirth. Foetuses that survive labour often do not live beyond one week.

The situation became overwhelming when Ms Cox’s doctor informed her that continuing the pregnancy until the foetus died inside her or could be delivered through labour risked her opportunity to have another child in the future.

Given the choice, Ms Cox opted to terminate her pregnancy through her doctor’s recommendation of a D&E.

But there was a problem.

At 20 weeks pregnant, Ms Cox’s doctor was unable to perform an abortion in the state of Texas legally.

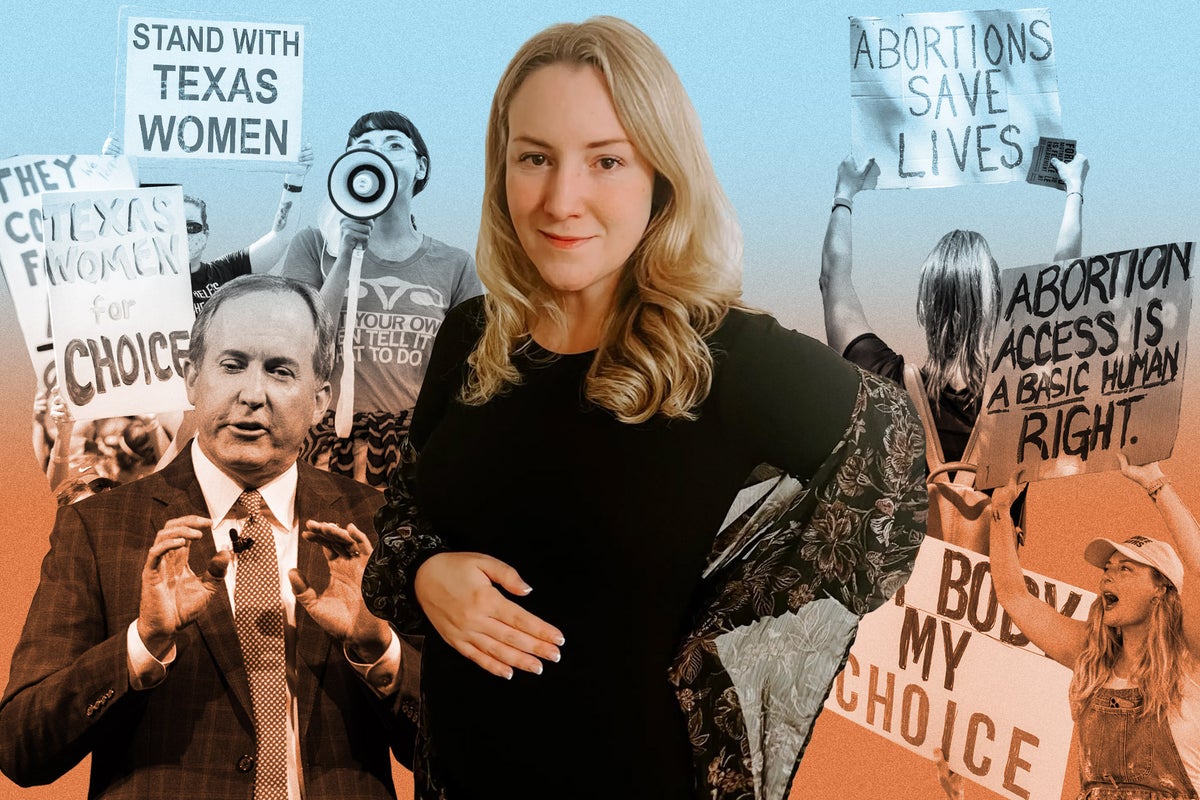

Kate Cox— (Kate Cox)

The law, enacted last year, bars abortion before a detectable foetal heartbeat unless a “reasonable medical judgment” determines there is a greater risk of the pregnant person dying or impairment of a major bodily function. But the law stops short of defining “reasonable medical judgment” or “major bodily function.”

Ms Cox would either have to travel out of state for the procedure or petition a court for a temporary restraining order (TRO) by convincing a judge that her unviable pregnancy was a risk to her.

“It is not a matter of if I will have to say goodbye, but when,” Ms Cox, represented by the CRR, wrote in her petition to the court. “I desperately want the chance to try for another baby and want to access the medical care now that gives me the best chance at another baby.”

‘Intentionally vague’ law takes center stage

For the first time since Roe v Wade was decided in 1973, a pregnant adult was forced to ask a state for permission to have an abortion. Immediately the state acted to push its anti-abortion agenda.

A lawyer in the Texas Office of the Attorney General argued to a district court judge that Ms Cox did not meet the law’s medical exemption criteria and that issuing the TRO would require changing the language.

“Lawmakers are essentially stepping in to dictate medical care,” Payal Shah, the program director on Sexual Violence at Physicians for Human Rights told The Independent.

It is the exact argument the CRR is currently litigating in Zurawski v Texas where 20 people are suing the state, claiming the law’s vague language caused them harm due to the inability to obtain medically necessary abortions.

The plaintiffs stand in front of the Texas Supreme Court after oral arguments for Zurawski v State of Texas were heard in Austin— (AP)

Hours after the TRO was granted, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sent letters to three hospitals where Ms Cox could potentially obtain her abortion, threatening legal action.

“The TRO will not insulate you, or anyone else, from civil and criminal liability for violating Texas’ abortion laws, including first-degree felony prosecutions,” Mr Paxton wrote.

Though Mr Paxton acknowledged it was hospitals that had the authority to decide when an abortion is needed he claimed Ms Cox’s doctor failed to follow proper procedures in determining a medical exception and that the TRO would not protect the hospital from future lawsuits.

Mr Paxton then asked the state supreme court to step in.

The court wrote that those who do qualify for an abortion, do not need a court order to obtain one.

But the ruling stated Ms Cox did not meet the medical exception criteria, claiming her doctor did not use “reasonable medical judgment” to recommend the D&E, just her “mere subjective belief”.

Ms Shah said that under the “reasonable medical judgment” standard, physicians’ decisions can be “opened up to scrutiny and second-guessing” which leads to serious health harm.

But the court itself offered little clarity on what the specific language means, instead, it asked the Texas Medical Board to provide guidance.

The medical exception is “intentionally vague because it’s all about control,” Dr Amanda Horton, an Austin-based OB/GYN and spokesperson for the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, said.

Sabrina Talukder, the director of the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress, understood the ruling to mean that Ms Cox’s condition “does not rise to the level of a life-threatening emergency that would warrant this medical exemption.”

But it raises the question: when is it necessary and who gets to decide?

Protesters outside the Arizona Capitol in Phoenix in 2022— (AP)

Doctors are in an ‘untenable position’

The interpretation is no clearer among doctors.

Dr Horton said based on her experience, the interpretation is up to the hospital. Some hospitals may allow for “physician autonomy” in making the decision that performing an abortion is necessary, while others may require the sign-off of the chief of obstetrics, while others still have ethics committees to make the determination.

“There is no regulatory process,” Dr Horton said.

Clinicians in states with abortion bans often find their hands tied for fear of retaliation. It changes the way doctors can document patients’ health, how they can counsel their patients and how they may be able to treat their patients.

Dr Horton said all doctors “take an oath to do no harm.” But due to the bans, if doctors advocate for their patients, they could also run the risk of “harming ourselves because, in the eyes of the law, we are felons,” she said.

“How close to death does someone need to be before we say it’s okay?” Dr Horton asked.

Since this case is unique, Ms Talukder said, there “isn’t anything that can help clarify” in Texas or other states as to what the outcome means

In Amanda Zurawski’s case, she needed to be fighting a life-threatening infection that ultimately caused her to lose a fallopian tube.

“Criminalizing abortion leads to making pregnancy dangerous and that is certainly the case in Texas,” Nicholas Kabat, a staff attorney at the CRR, said.

Demonstrators at the federal courthouse in Austin following the US Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v Wade in June 2022— (Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved)

Some providers in states like Texas, North Carolina, Ohio and Florida say they’ve left their states in order to give patients the best medical care they can. For now, this is an option but Mr Kabat raises concerns that should a federal 15-week ban be brought in, “this is what it would look like.”

Cases similar to Ms Cox’s are popping up around the US. In Tennessee, a woman sued the state for denying her a medically necessary abortion, saying the state’s medical exception was too vague.

As of November, 38 lawsuits have been filed challenging abortion bans in 23 states from both women and physicians, according to the Brennan Center.

The law is “having the effect of chilling care for people that are in need across the state,” Skye Perryman, CEO of Democracy Forward, said. “It’s an untenable position for medical professionals to be in.”

The CRR says while the Texas Supreme Court ruling was an upset for Ms Cox, it did not set precedent because it did not rule on the constitutionality of the issue. They’re hopeful that the court will issue a ruling in their favour that clarifies what medical exceptions mean and who gets to decide when they are necessary in Zurawski.

It is unclear if Ms Cox will continue pursuing her case. But her decision to throw herself in the line of fire has directed national attention to the problem with medical exceptions in anti-abortion laws.

“The Kate Cox case demonstrates that in states like Texas, there really is no such thing as an abortion exception,” Senator Tina Smith, the former vice president of Planned Parenthood of Minnesota, said.

“If she can’t qualify for an exception, who does?”

Eric Garcia contributed to this report