Over the past two decades, architect Abha Narain Lambah’s name has routinely cropped up in discussions around nearly every conservation project in the country — from the Mandu royal complex in Madhya Pradesh to Mumbai’s Opera House to Lalbagh Palace in Indore. Most recently, she prepared the dossier for Santiniketan’s inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Lambah’s work has brought new life to old buildings, sad and neglected in their isolation, now refreshed and ready, to have another lease of engagement with newer generations.

Her practice, based in Mumbai, has won several UNESCO Asia Pacific Awards for heritage conservation and is the largest architectural conservation practice in the subcontinent. And yet, Lambah’s lightness of being is at complete odds with her staggering body of work and the rigour and expertise required in the field. Ahead of her illustrated lecture in Chennai this weekend, Lambah discusses her new projects and her role in shaping government policy over the years. Edited excerpts:

How did you get into the world of architectural conservation?

When I was studying at the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi, I had the option to choose my dissertation/ thesis, and I chose Khirki, a medieval Tuglaq-period mosque surrounded by a settlement in Delhi. I had always admired American architect Joseph Allen Stein and wanted to work with him. During an interview at his studio, he observed my portfolio and remarked that while his studio focused on architecture, my interest seemed to lie in urban conservation. I thought he read me better as an architect. I eventually worked with Stein for about a year-and-a-half on the India Habitat Centre. His insight stayed with me, leading me to pursue a Master’s in conservation.

When I moved to Bombay after that, it coincided with the city adopting pioneering heritage regulations for India. At that time, I knew no one there. My husband and I had just moved there. Once, when we were at a restaurant, across from us sat a man engrossed in a fascinating conversation about Bombay’s history and heritage buildings with a British man. That was Rahul Mehrotra, whom I later approached for an interview. Rahul encouraged me to start my own practice, and I applied for an urban grant to establish conservation guidelines for the Dadabhai Naoroji Road (D.N. Road). That’s how it all began.

Do you find a growing sensitivity to conservation in India today?

When I commenced my practice 25 years ago, conservation in India was nascent both as a field and a profession. There was no funding, awareness, or government support apart from that for nationally protected monuments under the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

In Mumbai, where no building in the island city fell under ASI, 1995 regulations prevented potential demolition, yet funds were scarce. My initial projects were born from activism, focusing on historic neighbourhoods. The D.N. Road project, started in 1998, became India’s pioneering urban signage and streetscape endeavour, and was funded by individual stakeholders along the street.

I restored Elphinstone College pro bono because I was a founding member of the Kala Ghoda Association, raising funds from HSBC and Sir Dorabji Tata Trust. Shoestring-budget projects included restoring a building in Horniman Circle funded by local banks. These initiatives laid the framework for other projects and became precursors to multiple conservation endeavours. Corporate funding followed liberalisation, with international banks restoring heritage buildings. The Indian nationalised banks got onto the bandwagon a decade-and-a-half later. I think the last one to get into conservation was the government. Today you have so much government funding, which was completely unheard of 25 years ago.

What has been your role in contributing to government policy in your many projects over the years?

Restoring Elphinstone College using non-abrasive cleaning and lime mortars set a precedent. It introduced the Public Works Department of Maharashtra to alternative heritage conservation methods, prompting the State to allocate funds and implement conservation specifications for various buildings like the Town Hall, Asiatic Library, and Bombay High Court.

In 2009, I was appointed by the ASI to craft the management plan for Ajanta Caves, marking the first instance they hired external consultants for a UNESCO World Heritage site. This approach brought multidisciplinary expertise, showcasing the necessity of such approaches for historic sites and nomination dossiers, evident in efforts such as proposing Santiniketan for a UNESCO listing.

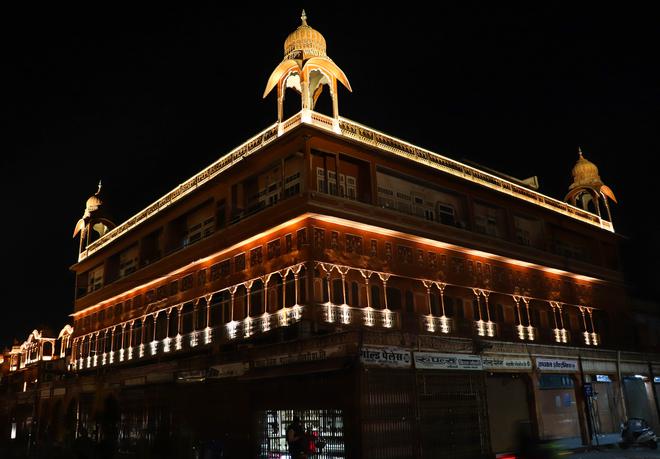

Now, State and Central governments increasingly engage professional firms for such endeavours, utilising funds from initiatives such as smart city programmes for illuminating heritage structures and spaces — like the historic areas and dargahs in Srinagar. The impact of illumination here was iconic because Srinagar had no night life post militancy in the 1980s, it was just dark and gloomy. Now, areas such as Lal Chowk and Polo View, post-pedestrianisation and illumination, have revitalised the city’s nightlife and local engagement. This transformation encourages tourism and instils a sense of vibrancy in the local community.

Similarly, in another instance, about a decade ago, Vasundhara Raje, then Chief Minister of Rajasthan, proposed illuminating the walled city of Jaipur. Her vision stemmed from the scorching daytime temperatures and heavy traffic discouraging people from shopping or exploring the city during the day.

Given a nine-month timeline, we embarked on a project to illuminate the major bazaar streets alongside iconic structures like the Hawa Mahal. This initiative transformed into the first night tourism illumination project, supported by the tourism ministry. The aim was to create an inviting atmosphere for heritage tours, reduce congestion and allow visitors to appreciate the city’s architecture under the calming ambience of night-time illumination.

What are the different dynamics involved in government or public projects and private projects? And how do you cope with the famous Indian bureaucracy?

Honestly, I’ve encountered remarkably genuine individuals within Indian bureaucracy and politics, often surprising me with their sensitivity. There have been instances where one official might dismiss heritage concerns, and their replacement is almost an evangelist for heritage. It’s a fluid landscape. Similar unpredictability extends to private owners. Some exhibit frequent changes of mind while others place immense trust in your judgement. For instance, the Maharaja of Gondal, owner of Mumbai’s Opera House, exemplified unwavering trust. He never questioned estimates, never interfered with designs, and wholeheartedly supported my decisions throughout the project.

Do you follow specific UN standards in your work? Are there local standards? Or is each project based on the clients and what they want done?

Certainly, conservation adheres to benchmarks and encompasses various aspects — restoration, reconstruction, preservation, and structural stabilisation — each with its nuances. In the case of Mumbai’s Opera House which was completely dilapidated, our aim was to restore it to its original grandeur. This meant meticulous attention to design, materials, and services. Technology also plays a part, we had to seamlessly integrate air conditioning, the best acoustics available in the market today, and everything else. Despite integrating modern necessities, our focus remained on replicating the original colour palette and designs, relying on historical photographical evidence we had.

In the case of the restoration of Lalbagh Palace, it underwent intense scrutiny, aiming for an authentic period-specific interior. Every detail, from reweaving frayed fabrics to updated damask upholstery patterns, was meticulously recreated to match the original. The team, led by Anupam Shah, painstakingly restored painted ceilings and ensured accuracy down to the minutest details. Peer reviewers from the World Monuments Fund in New York vetted our conservation plan to ensure approval for every aspect of our work.

What are your upcoming projects?

I’m currently working at two ends of the country, from the exciting conservation of Shalimar Bagh in Kashmir, to the Victoria Public Hall in Chennai, which is such a beautiful elegant building. We are working on the roof and the structure. So that’s well underway.

Chennai has some gorgeous public buildings, from the High Court to the General Post Office to the railway stations. I would love to work on some of these, and adaptively reuse some. I would also love to work on a UNESCO nomination dossier for Kancheepuram city. We were appointed as city anchors for Kancheepuram, so we worked there a lot, and the city is definitely deserving of a world heritage status.

The lecture in Chennai is part of Prakriti Foundation’s 25th year celebrations.

The interviewer is a cultural activist, philanthropist, and founder of Prakriti Foundation.