On the wall of Stenbock House, my Lunch guest’s office in the heart of Tallinn, are two modest stone plaques. They record the names of all 10 Estonian heads of government and 56 other ministers who perished in the Communist terror that began in 1941. The past and present are never far apart in Estonia’s capital.

Estonia has been on the frontline between Nato and Russia ever since it joined the military alliance in 2004. But the security situation in the Baltics and Europe as a whole in recent weeks has been at its most tense in decades after Russia massed troops on Ukraine’s border and also in Belarus, close to the narrow land border that ties the Baltics to the rest of Europe.

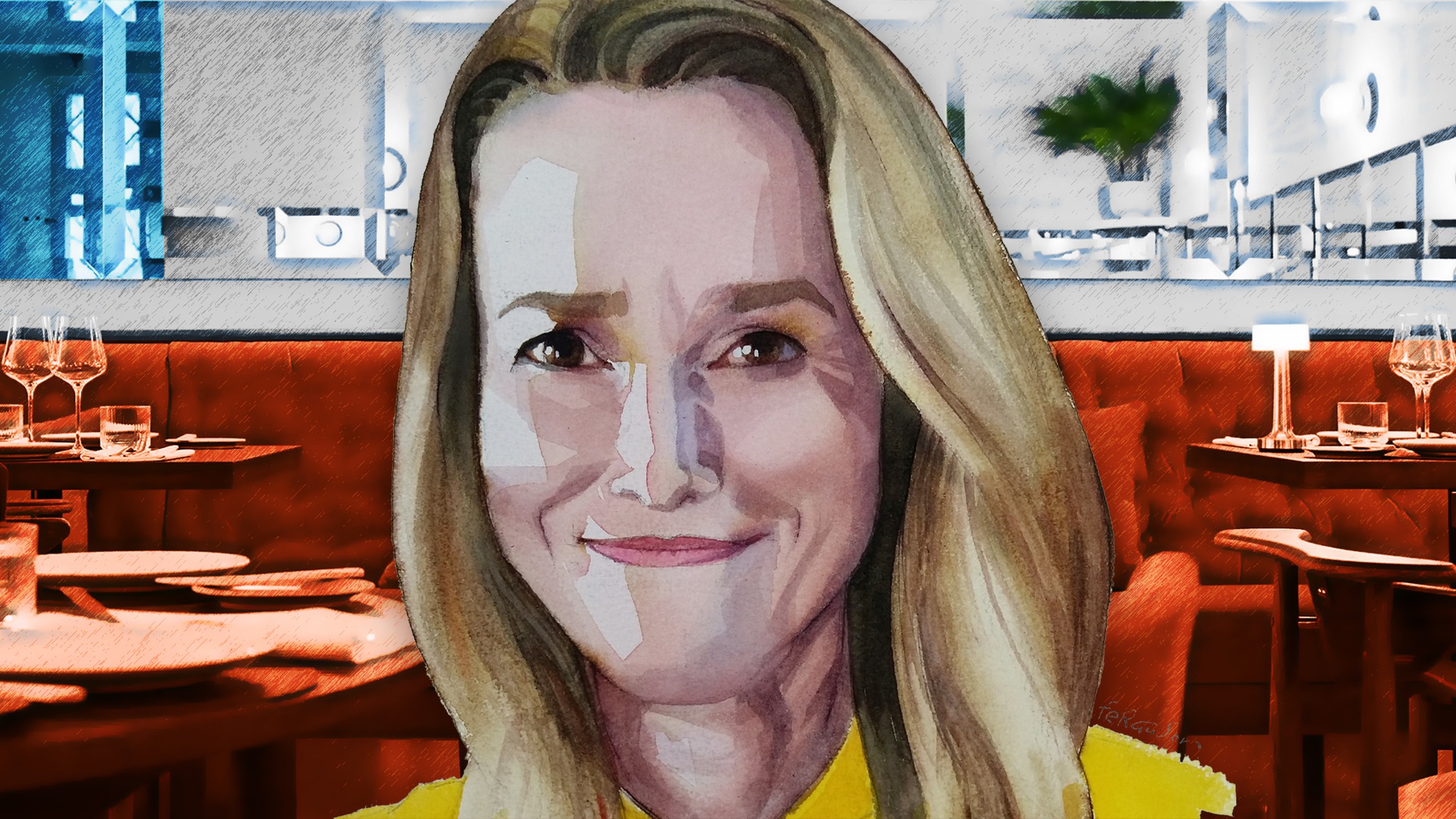

I meet Kaja Kallas, Estonia’s prime minister for the past year, in an Estonian-Japanese fusion restaurant at the foot of the Hanseatic old town’s ramparts, entering through a garden furnished rather incongruously with busts of Sean Connery and Alexander Fleming. The Scottish Club, it turns out, is also based here.

The restaurant has opened especially for us, and the gentle thump-thump of dance music replaces the buzz of other diners. I greet Kallas, who is wearing a pale yellow dress with a large brooch of the Estonian flag, with one of my first handshakes in two years.

We are meeting in the second week of February before this week’s whirlwind diplomacy. She sounds understandably steeled for adversity, not just with respect to the stand-off over Ukraine but also the stakes for Estonia and its two fellow Baltic countries, Lithuania and Latvia, if President Vladimir Putin is emboldened.

“Of course, we are members of Nato, so it’s a bit different attacking a member of Nato to attacking Ukraine [a non-member],” she says. “But, still, if he gets away with Ukraine, they’re just pushing the boundaries even further and probably having this view: ‘How can we really move on?’ ”

The waitress has brought us dark rye bread and butter, and informed us that we will be sharing a selection of three starters, two main courses and a dessert in a fusion of Estonian produce and Japanese techniques. The starters soon arrive: trout crudo, roast pumpkin and a potato omelette. We’re left to share it out ourselves, and I note wryly that while I take half of everything, Kallas serves herself smaller portions.

Kallas, who is still relatively new to the job, may lead one of the least populous countries in the EU — Estonia has just 1.3mn people — but both she and her country have an outsized place in the western debate. Estonia has become Europe’s leader in digital government and education, all the while keeping its guard up against its bigger neighbour and former occupier to the east.

Menu

Lee Restoran

Uus 31, 10111 Tallinn, Estonia

Set menu x2 €90

Kallas talks about a five-and-a-half-hour cabinet meeting the previous week to discuss the preparedness of Estonia for conflict or hybrid attacks such as cyber warfare. “What do we do when there’s no electricity? What do we do when there’s no internet? How do these things function? How do we pay out the pensions?” she says, adding that Estonia’s mantra is: “Prepare for everything and if nothing bad happens, then fine, we’re positively surprised.”

French President Emmanuel Macron had visited Moscow the day before. I ask Kallas her views on the wisdom of such a bilateral visit when she and others have stressed the importance of Nato unity, a unity that has until now held surprisingly well.

“I’m wondering how frank I can be,” she says, before having a mouthful of the trout and making her mind up: “I feel there is a strong wish to be the hero who solves this case, but I don’t think it’s solvable like that.”

Kallas adds: “There seems to be a certain type of naivety towards Russia. I was trying to explain this to President Macron as well: you’re seeing this through the prism of a democratic country. You say that’s it’s going to be super-expensive for Russia to have a war . . . [Putin] doesn’t care. He’s not up for elections.”

The turbulent history of Estonia, which was annexed after the second world war by the Soviet Union, gives it a particularly acute perspective, I suggest. Estonia had declared independence in 1918 after periods in both the Swedish and Russian empires, but was promptly invaded by first Germany and then Soviet Russia, before two decades of relative peace before the second world war. During the conflict, it was first occupied by Soviet forces, then by the Germans and finally by the Soviets again.

“We have seen very closely how this works and how the thinking goes,” says Kallas. “They [western European leaders] don’t have the experience like this.” She adds that the west would be better served with “strategic patience” rather than rushing to offer Putin something. But she worries that with a new German government, French elections on the horizon and the Biden administration in the US, Putin “definitely sees the opportunity there”.

For Kallas, as for most Estonians, this history is intensely personal. Her great-grandmother, grandmother and mother — then just six months old — were deported to Siberia in March 1949. The journey took three weeks in a cattle wagon, an ordeal that a baby was not expected to survive. A gift of milk at one station on the way, and the kindness of strangers keeping the baby warm and drying her nappies on their bodies, helped keep her mother alive.

The family did well there, a Singer sewing machine that they took with them helping to provide an income in the frozen north. It was quite a fall from grace for the family; Kallas’s great-grandfather was one of the founders of an independent Estonia in 1918, and the first chief of its secret police.

Kallas, who is 44 and spent much of her childhood in Soviet times, relates her surprise when her grandmother told her stories from before the war when she was a governess in Finland, a short distance across the Gulf of Helsinki from Tallinn. The younger Kallas could scarcely believe her grandmother that foreign travel was possible.

They had the freedom, they had all the choices, they had a free world. Everything was taken from them

“If I compare my generation to my grandmother’s generation, they had everything. They had the freedom, they had all the choices, they had a free world. Everything was taken from them. And I’m absolutely the opposite generation. We didn’t have anything, we didn’t have choices, we didn’t even have anything in the shops. Then we got everything, in 1991 we got our freedom back,” she says.

One particular hardship stuck in her mind. “We had a time when we didn’t have any candies in the shop. We ate sour cream with sugar. That was the sweetest thing that we could get, so I remember those days,” she adds.

When I mention the plaque outside Stenbock House, she asks me if I have visited Estonia’s new memorial to victims of Communism. I say no. “I was just thinking that if we had chosen another restaurant closer to it, I could have shown it to you. It’s very powerful,” she adds.

That memory of the terror and deprivations of Soviet rule, and an intense desire never to return to those days, explains why Estonia has consistently warned the west about the dangers of a revanchist Russia, especially after Putin’s first aggression in Georgia in 2008 and even more so after its 2014 annexation of Crimea. “A basic principle of our foreign policy is that we are never alone again. Because, in the 1940s, we thought that we didn’t need anybody. Then we were left alone, which our big neighbour took advantage of,” Kallas explains.

I suggest to her that one of the dividing lines between western and eastern Europe is their differing views of the second world war. In the west, Nazi Germany tends to be seen as the sole aggressor. But in the east, there are long memories too of the crimes and abuses by the Soviet Union.

Kallas says the difference is most vivid on May 9, commemorated as Victory Day in western Europe for the surrender of Nazi Germany. “It could be a good day for us as well if on May 10 Stalin had said: ‘You’re all free, go back to being independent countries.’ Whereas he didn’t. Then the atrocities started for us — the deportations, the mass killings, the pressure on our culture, the collectivisation,” she says.

“A lot is talked about the Nazis, the Holocaust. But there were so many victims of the Communist regime that are not much talked about, even in our country.”

Our first main course of pike perch arrives, providing a break in conversation. Kallas divides the fish and its Asian-inspired vegetables in two, and reels off a series of statistics about Estonia’s progress since regaining independence in 1991. Wages have grown 45-fold, pensions 60-fold, and its income per capita, which was once 40 per cent of the EU average, is now 86 per cent and bigger than that of Greece, Portugal or Poland.

She underscores: “Just before coming here, I was checking the numbers . . . Our development has been quite rapid, but for me it’s very important to understand that it’s not for granted. We could lose it all again.”

Like many in northern Estonia, Kallas had a porthole into life outside the Soviet Union through the ability to pick up Finnish TV. “We saw everything there, and we were not naive. We didn’t believe that in the Soviet Union there was a better life, because we saw it very clearly on the Finnish side,” she says.

She experienced the build-up to regaining independence at close quarters as her father, Siim Kallas, was one of the driving forces, later becoming head of the central bank, finance and foreign ministers, as well as prime minister. She talks of being allowed to remain at the table as tactics were discussed.

She recounts a trip to East Germany her father took her on before the fall of the Berlin Wall when she was about 10. “I remember when my father said: ‘Children, breathe in, it’s the air of freedom that comes from the western side.’”

She started studying and then practising law at a fertile time as new rules and regulations were being written after the regaining of independence. A partner at Estonia’s second-biggest law firm at 27, in her 30s she suddenly felt an itch no longer to be a mere adviser but to make decisions and try to improve the country.

She joined the Reform party and became an MEP. In Brussels, she gained a reputation as one of the stars of the parliament, with a particular focus on technology matters, perhaps no surprise when Estonia has the most advanced digital government in Europe. In 2000, Estonia discarded paper documents and introduced a digital system for cabinet meetings while citizens have been able to vote, fill in tax returns and do pretty much every other bureaucratic task electronically for more than a decade.

Kallas has indeed been compared, often negatively, to her father. But she adds of one proud moment when a woman wrote to her saying she had been photographed with Siim Kallas and that her daughter had remarked on seeing the picture: “Oh, you got a picture with Kaja’s father.”

I had no illusions about the job and had seen from my father how difficult it is. But, of course, he says that he never had as difficult times as I’m having

Her time as prime minister has been tough, especially as she assumed office in the middle of the pandemic. She relates how she chaired a cabinet meeting to impose fresh restrictions on her first day in charge. She has suffered in the opinion polls as voters struggle to work out what she and her liberal Reform party stand for.

Some of the criticism has been fierce and personal. Andrus Ansip, a former Reform prime minister, called her a “selfish, ‘to the manor born’ lady” after she said she had considered resigning but decided not to as it would bring the controversial nationalist Ekre party to power. Kallas deflects my question but concedes: “I had no illusions about the job and had seen from my father how difficult it is. But, of course, he says that he never had as difficult times as I’m having.”

The waitress brings over new knives and forks for our second main course. I have a sense of relief when Kallas tells her that she is full. Dessert, however, is non-negotiable. A cute take on kohuke, a chocolate-covered curd cheese snack, soon arrives, filled with cherries. We ask for some green tea, and some small cookies appear too; Kallas says it was these that attracted her to the restaurant first in an earlier location.

Some have suggested that the big advances in digital government in Estonia have rather stalled in recent years. Is it time to reinvigorate the concept? Kallas agrees, saying the new thing is what she calls “proactive government services”, where the administration can, for instance, automatically set up child benefit when a baby is born or send out a message saying a driver’s licence will soon expire and provide the link to order a replacement. She says it’s “a positive side of being a small country — you can easily turn a small ship whereas you can’t turn a big ship.”

Kallas suddenly takes up her phone, checks the time, and sends a quick message. “Are you in a rush?” she asks. We eat a few of the tiny cookies and she says she has just calculated she has time before her next meeting to take me to the Victims of Communism Memorial.

The memorial is several kilometres outside the city centre and when we get there it is snowing, and a biting wind is blowing off the sea. Kallas, now clad in a thin, beige hooded coat, strides out of the car and shows me the long columns detailing thousands upon thousands of Estonia’s victims to Communism. We walk up some steps to a section with bullet holes, each containing the picture of an Estonian military officer. Different sections explain the different parts of Siberia, and elsewhere in the Soviet Union, to which victims were deported.

“Sorry for the weather,” she exclaims once we are in the car again. As we speed back to the centre of Tallinn, I return to the events of today. Is it Putin’s aim to keep the Baltics permanently on their toes, never able to let their guard down?

“Yes. This is what I sometimes feel around the European Council discussions. For some of those people, it is a theoretical discussion. Whereas for us, it’s an everyday worry, a real worry. I would love to invest all this money that we invest in defence, in education, but being an independent country and the things that we have to do for this, we don’t really have an option.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022