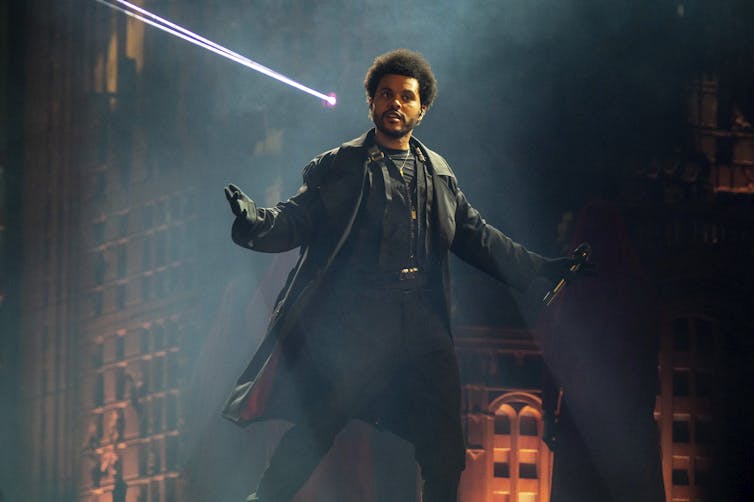

As we celebrate another year of Canadian music at the Juno Awards, let’s consider the broader music ecosystem that facilitates a vibrant component of our multifaceted culture and identity.

An essential component of this ecosystem supporting musical artists has been the policy of Canadian Content (CanCon) regulations for music radio.

CanCon policy hasn’t only ensured Canadian music is played on the radio, but notably, that radio profits are redistributed to artists through grant programs — something critical for artists’ viability and success.

Revitalization in digital era

Currently, there is debate on how to implement similar regulations for streaming media. Bill-C11, An Act to amend the Broadcasting Act and to make related and consequential amendments to other Acts has been passed by the Senate (with contentious amendments), and is now being debated in the House.

The few large multinational corporations that make use of Canada’s creative sector should also contribute to the public funding of the arts, contributing to the revitalization of music in Canada in the digital era.

Music industry highly consolidated

On one hand, the music industry in Canada is highly consolidated, with three record labels (Universal, Warner, Sony), three streaming companies (Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music), and one live concert and ticketing company (LiveNation/Ticketmaster).

They are all non-Canadian. They have market power that shapes the industry to favour superstars, lessens the ability of working musicians to make a living wage and limits the diversity of Canadian music.

On the other hand, public programs support diverse Canadian music heritage and the development of Canadian artists. This year’s Juno nominees include at least 85 artists who have received a total of 433 grants from FACTOR (The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings).

Read more: Junos 50th anniversary: How we remember these award-winning hit singles

FACTOR, along with public and community radio, the Polaris Prize, provincial music industry associations and other public-serving organizations and regulations help ensure the diversity and abundance of music outside of the purely profit-driven system.

Bill C-11

Bill C-11 has potential to address the limitations of the corporate music model and provide musicians with more opportunities to earn a livelihood by increasing opportunities for grants. But these concerns have been overshadowed by the sprawling nature of the bill and its legislative amendment process.

Bill C-11 proposes an update to the Broadcasting Act to include online platforms in CRTC regulation and CanCon rules.

In terms of streaming music (like on Spotify or Apple Music), this would mean including music by Canadian artists on the curated playlists provided by the platform, and companies paying in to a media fund that would provide grants for Canadian artists.

Algorithms are not neutral: they train us as much as we train them. Using them to promote local music or Canadian music may inspire a wider variety of music heard on streaming services.

Regulations done properly

Some critics say C-11 would cause financial hardship and unintended consequences for content creators and open the door for CRTC interference in freedom of expression and lead to government control over social feed algorithms.

Many remain unconvinced that the centralization of regulation is worth the overreach of the bill.

Researchers in public policy and communications have amplified some creators’ concerns that given the role of broadcasting as a settler nation-building project entrenched in systemic racism, new policy would need to do more to safeguard interests of Black, Indigenous and racialized content creators.

Major Senate change

A major Senate amendment proposed limiting the bill to maintain the autonomy of individual creators posting online, and curbing the CRTC’s discretionary power.

But Pablo Rodriguez, Minister of Canadian Heritage, has rejected Senate amendments and the process is yet again under fire.

The non-profit Open Media dedicated to “keeping the internet open, affordable and surveillance-free,” notes a key Senate amendment “considerably reduces the risk of ordinary Canadian user-uploaded content being regulated as broadcasting content” but flags problems with how age restrictions on content would be managed.

It’s good to have critics ensure regulations benefit all artists and users and that the bill does not tell people what to create. Yet much of the writing on C-11 has dismissed CanCon regulations for the streaming era altogether.

Read more: Should we be forced to see more Canadian content on TikTok and YouTube?

Why CanCon matters

In radio, CanCon refers to regulations that began in 1971. By playing more music by Canadians on the radio (initially 30 per cent Canadian music over the broadcast week, now at least 35 per cent), the aim was to grow domestic music industries.

In the same era, major labels invested in Canadian record pressing plants to help overcome the costs of importing records.

By the end of the 1970s, evidence of music industry growth in Canada was apparent, with more recording taking place in studios and an increase in performance royalties being paid to songwriters.

Music grants for artists

Two avenues of support for artists in Canada are campus/community radio and grants, often from FACTOR.

Our research found artists overwhelmingly emphasize the importance of grants to their careers. While some note barriers to access with writing and receiving some grants, grant funding remains crucial.

Both the Community Radio Fund of Canada and FACTOR receive money from Canadian Content Development (CCD) contributions. These come from commercial radio stations with annual revenue above $1,250,000. English-language stations that meet this criteria pay $1,000 plus half a per cent on all revenues above $1,250,000.

To support music in Canada, corporate music streaming services should pay into CCD funds.

Lower charting success

Our research has documented a decline in the number and variety of charting artists and songs today in Canada which coincides with lower charting success of Canadian artists. This can be correlated to a lack of CanCon regulations in streaming, versus in the 90s when CanCon regulations affected how Canadians listen to music.

In satellite radio, CanCon regulations mean a certain per centage of channels must be Canadian. While these regulations aren’t perfect (Canadian channels are grouped together far down the channel lineup), artists have benefitted from royalties.

This was made evident in the uproar surrounding the cancellation of CBC Radio 3 on SiriusXM, a channel that was a stable source of income for artists and labels.

Beyond reforms to C-11, we argue guidelines governing corporate mergers should centre the concerns of workers and consumers, benefiting many sectors in Canada, including music.

Both government actions would help address the most immediate danger facing Canadian music today: media consolidation.

Brian Fauteux has received past funding from SSHRC.

Andrew deWaard has received past funding from SSHRC.

Brianne Selman has received past funding from SSHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.