Junior doctors heading into pay negotiations say they are now earning less than their nursing counterparts and in an environment where having a family is frowned on and flexible working is rare

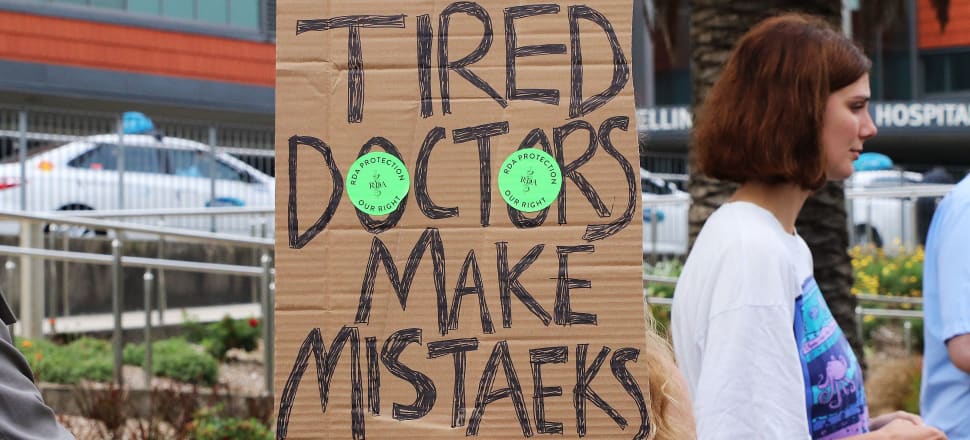

Half of the country’s junior doctors head into pay negotiations with Te Whatu Ora in a few weeks calling for a sizeable pay rise that acknowledges they are valued in the same way nurses have been in recent settlements.

Their pay talks fall at the same time senior doctors are preparing for strike action after deadlocked pay negotiations with Te Whatu Ora and hospitals prepare for non-urgent surgeries to be put on hold as a result.

Resident Medical Officers, or junior doctors, have had increasing hours and have continued to drop behind in pay because of inflation and a pay freeze.

READ MORE:

* ‘Even the introverts are here’: the return of the climate strike

* Making a point with a protest

Christina Matthews is training as an ear, nose, and throat specialist, and is on maternity leave, while continuing to negotiate for her colleagues as an official for Specialty Trainees of New Zealand – one of two unions representing junior doctors.

Matthews said the approach by the union had always been to collaborate and work with Health New Zealand to find solutions that will work within a stretched workforce and to avoid any strike action.

Heading into negotiations she said the biggest talking point for members was that a first year doctor with six years’ worth of study and student loan, who was working more hours on average, was now being paid less than a first year nurse with three years of study, fewer rostered hours and a smaller student loan.

“It’s not until very late in our category steps that we overtake them. It’s very hard to justify paying a doctor less than a nurse of the same level.

“It’s the responsibility where you go to work every day and it’s your name on the scripts, on decisions being made, and we’re not getting valued,” she told Newsroom.

“Because of that we’re seeing junior doctors leave for Australia … and the workforce crisis is so bad we aren’t getting trained well enough.”

In a statement to Newsroom, Te Whatu Ora spokesperson Andrew Slater said the organisation looked forward to addressing a range of matters with the union when bargaining discussions commence but it wouldn’t be appropriate or in good faith to comment on bargaining before it starts.

He said a number of collective agreements were being worked through with different professional groups and they expire at different times across the year.

“This may impact on relativity of salaries for short periods of time.”

Specialty Trainees of New Zealand wants some quick solutions to retaining the junior doctor workforce.

“We’re really worried we’re going to be in dire straits from a junior doctor perspective very soon, and also we’re going to come out as poorer consultants knowledge-wise, so we need to start being valued just like the nurses have been valued,” Matthews said.

Obstetrics and gynaecology trainee Jordan Tewhaiti-Smith is also a union official, and told Newsroom senior doctors had never gone on strike before and that showed a “huge appetite for some urgent change”.

“It’s concerning sitting here as a junior registrar with lots of my training ahead of me when all you hear in the headlines is that the SMOs [senior doctors] are about to strike and are in talks about their working conditions.

“Ultimately they’re the people training us, and if they’re not here how are we going to become competent and confident surgeons in the future?” Tewhaiti-Smith said.

Working and studying takes a toll

Junior doctors are all required to sit specialist exams, which requires part-time study alongside full-time work for anywhere up to 18 months.

Tewhaiti-Smith said studying alongside working 60-70-hour weeks had a “huge impact on your family life or even planning for a family”.

“That’s a toll that not many people see either.”

As negotiation nears, union members worry Te Whatu Ora doesn’t quite understand how undervalued junior doctors feel especially after years of Covid and a pay freeze.

Matthews said the union doesn’t want to take anything away from the success of the nurses securing the significant deal they negotiated, given the long entrenched problems they had faced, but wanted to see the same value put on junior doctors.

“They don’t quite see that you can’t just value one workforce, because you’re seeing leeching from everywhere. The nurses are the biggest drainpipe at the moment but as soon as there’s a plug put on that the other ones are going to burst and we’re not going to keep up.

“There needs to be appreciation across the board and I’m not sure Te Whatu Ora understands that.”

Health Minister Ayesha Verrall told Newsroom conditions needed to be raised for all the professional groups across the board because of how they affect each other.

She gave the example that the huge number of nursing vacancies had affected senior doctors and fixing that had in turn solved some of the concerns raised by doctors in their negotiations.

On the junior doctors bargaining, she said she’d been clear with Te Whatu Ora that it had “the ability to make a fair offer and we really value the work done by all our staff including junior doctors”.

Flexibility missing from healthcare

Alongside appreciation and pay, Matthews said there were systemic discrimination problems that needed to be addressed.

“I’ve seen a whole lot of women leave the public health system and go to community-based specialities because of a lack of flexibility within the workplace, a lack of mentorship and leadership.

“I have been in departments that have been heavily male and been fantastic, but I’ve also been in departments that were heavily male and not fantastic, and I considered leaving.

“I wasn’t treated equal, I was put under a microscope much more than my male colleagues,” she told Newsroom.

“I’ve had comments through my training that I should wait until the end to have kids, and if I’m sure I want to be doing this when I was already pregnant.”

Matthews said there were other marginalised communities in the health workforce too – males were also discriminated against and there was “underlying racism in the system” and problems for the LGBTQI community too.

Verrall told Newsroom she was “disappointed but not surprised” junior doctors were still being told not to start families until they’ve finished training.

“If anyone is giving that advice today, they need to look around and see that’s not true and that training while having kids can be enabled.”

She said flexibility in the workplace needed to be improved.

“More can be possible than what we do at the moment. I am aware of stories that are wrong, where people who want to be parents are told that’s going to be difficult to accommodate.

“There are instances of a lack of flexibility, and I’m pleased with the conversations I’ve had with Te Whatu Ora, that they are prepared to be more modern about that.”

Slater told Newsroom he hadn’t received any specific reports that doctors wanting to become parents were being discouraged from doing so.

He said any discrimination was “unacceptable and concerning” and should be reported so it could be investigated and dealt with.

National’s health spokesperson Shane Reti said the reports from Specialty Trainees of New Zealand were “completely unacceptable in a modern world” and it was his belief “unconscious bias” existed in the health system.

“If you want a healthcare force to look and represent like those you serve, you need to have policies to accommodate that actually, so that’s very disappointing to hear,” he told Newsroom.