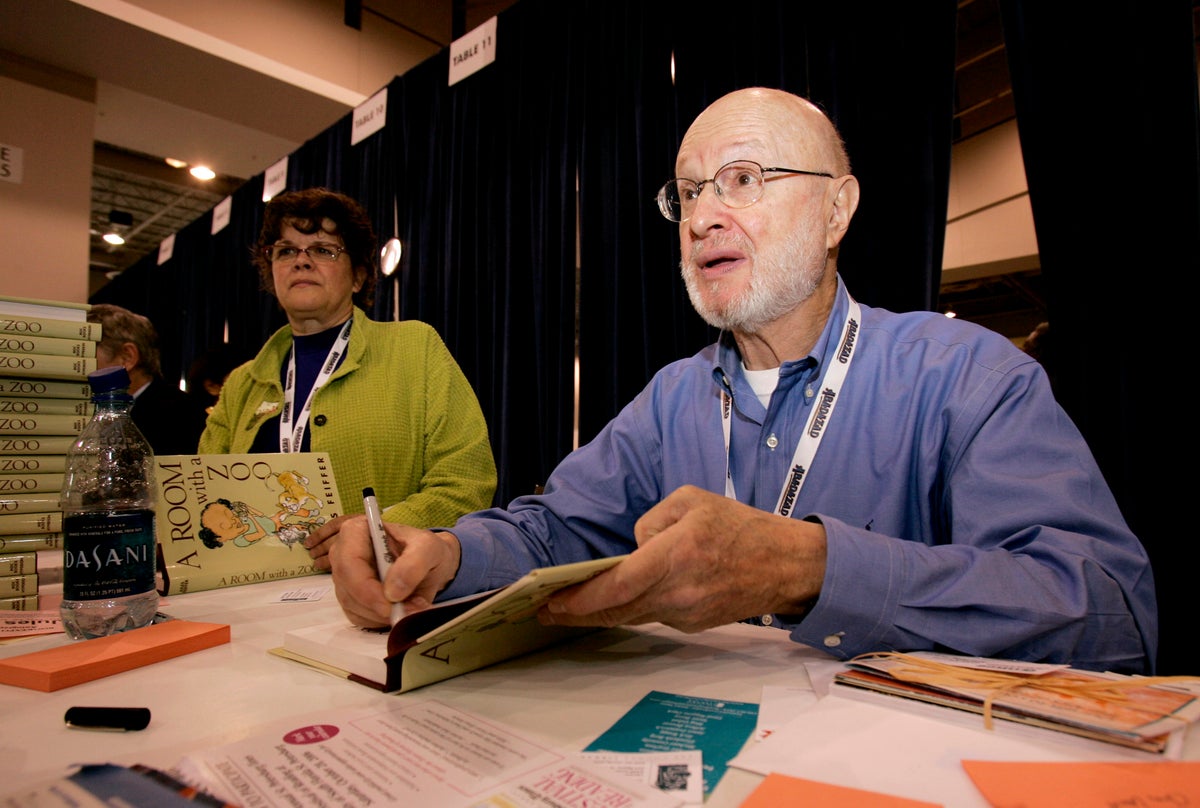

Jules Feiffer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and writer whose prolific output ranged from a long-running comic strip to plays, screenplays and children's books, died Friday. He was 95 and, true to his seemingly tireless form, published his last book just four months ago.

Feiffer's wife, writer JZ Holden, said Tuesday that he died of congestive heart failure at their home in Richfield Springs, New York, and was surrounded by friends, the couple's two cats and his recent artwork.

Holden said her husband had been ill for a couple of years, “but he was sharp and strong up until the very end. And funny.”

Artistically limber, Feiffer hopscotched among numerous forms of expression, chronicling the curiosity of childhood, urban angst and other societal currents. To each he brought a sharp wit and acute observations of the personal and political relations that defined his readers' lives.

As Feiffer explained to the Chicago Tribune in 2002, his work dealt with "communication and the breakdown thereof, between men and women, parents and children, a government and its citizens, and the individual not dealing so well with authority."

Feiffer won the United States' most prominent awards in journalism and filmmaking, taking home a 1986 Pulitzer Prize for his cartoons and “Munro,” an animated short film he wrote, won a 1961 Academy Award. The Library of Congress held a retrospective of his work in 1996.

“My goal is to make people think, to make them feel and, along the way, to make them smile if not laugh,” Feiffer told the South Florida Sun Sentinel in 1998. “Humor seems to me one of the best ways of espousing ideas. It gets people to listen with their guard down.”

Feiffer was born on Jan. 26, 1929, in the Bronx. From childhood on, he loved to draw.

As a young man, he attended the Pratt Institute, an art and design college based in Brooklyn, and worked for Will Eisner, creator of the popular comic book character The Spirit. Feiffer drew his first comic strip, "Clifford," from the late 1940s until he was drafted into the Army in 1951, according to a biography on his former website. He served two years in the Signal Corps, according to the online biography.

After the Army, he returned to drawing cartoons and found his way to a then-new alternative weekly newspaper, The Village Voice. His work debuted in the paper in 1956.

The Voice grew into a lodestar of downtown and liberal New York, and Feiffer became one of its fixtures. His strip, called simply "Feiffer," ran there for more than 40 years.

The Voice was a fitting venue for Feiffer's feisty liberal sensibilities, and a showcase for a strip acclaimed for its spidery style and skewering satire of a gallery of New York archetypes.

"It's hard to remember what hypocrisy looked like before Jules Feiffer sketched it," Todd Gitlin, who was then a New York University journalism and sociology professor, wrote in Newsday in 1997. Gitlin died in 2022.

Feiffer quit the Voice amid a salary dispute in 1997, sparking an outcry from readers. His strip continued to be syndicated until he ended it in 2000.

But if "Feiffer" was retired, Feiffer himself was not. He had long since developed a roster of side projects.

He published novels, starting in 1963 with “Harry the Rat with Women.” He started writing plays, spurred by a sense of sociological upheaval that, as he later told Time magazine, he felt he couldn't address "in six panels of a cartoon."

His first play, 1967's “Little Murders,” went on to win an Obie Award, a leading honor for Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway productions.

He ultimately wrote over a dozen plays and screenplays, ranging from the 1980 film version of the classic comic "Popeye" to the tougher territory of "Carnal Knowledge," a story of two college friends and their toxic relationships with women over 20 years. Feiffer wrote the stage and screen versions of "Carnal Knowledge," which was made into a 1971 movie directed by Mike Nichols and starring Jack Nicholson, Art Garfunkel, Candice Bergen and Ann-Margret. Feiffer also contributed to the long-running erotic musical revue "Oh! Calcutta!"

But after disappointing reviews of his 1990 play "Elliot Loves," Feiffer looked to the gentler realm of children's literature.

“My kind of theater was about confronting grown-ups with truths they didn’t want to hear. But it seemed to me we’ve reached the point, at this particular time, where grown-ups knew all the bad news. ... So I hunted around for people I could give good news to, and it seemed to me it should be the next generation,” Feiffer told National Public Radio in 1995.

Having illustrated Norton Juster's inventive 1961 book “The Phantom Tollbooth,” Feiffer brought a wry wonder to bear on his own books for young readers, starting with 1993's "The Man in the Ceiling." A musical version premiered in 2017 at the Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor, New York.

The theater threw a surprise 90th birthday party for Feiffer in February 2019, when he did an on-stage interview to accompany a screening of “Carnal Knowledge.”

In recent years, Feiffer also painted watercolors of his signature figures and taught humor-writing courses at several colleges, among other projects. He published a graphic novel for young readers, “Amazing Grapes,” last September.

His wife said he had great fun writing it, relishing the drawings and story.

“He was,” she said, “a 5-year-old living in a 95-year-old's body.”

___

AP National Writer Hillel Italie contributed.

___

This story was corrected to show that “Munro" won an Academy Award was 1961, not 1958.