Lawyers for Donald Trump’s administration are refusing to answer who gave the order to ignore a federal judge’s ruling that blocked the government from deporting dozens of immigrants under the president’s use of the Alien Enemies Act.

District Judge James Boasberg grilled government lawyers at a hearing in Washington, D.C., on Thursday to determine whether the government intentionally defied his court orders to turn planes around before they were emptied out into a notorious prison in El Salvador last month.

The administration appeared to be acting in “bad faith” after his court orders, Boasberg said.

“If you believed everything you did was legal, I can’t believe you would have operated the way you did that day,” he said.

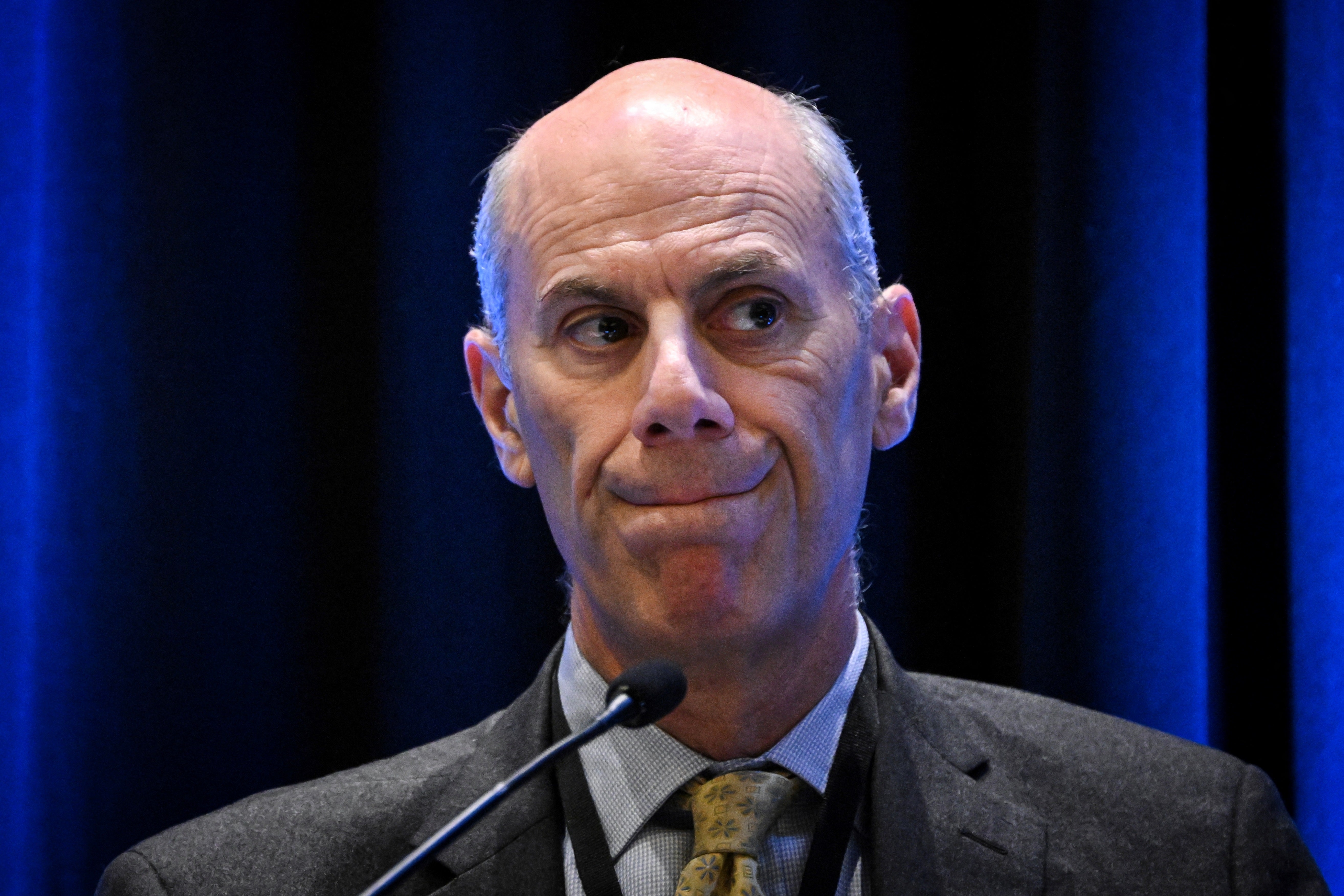

Deputy assistant attorney general Drew Ensign repeatedly said his conversations with administration officials about Boasberg’s orders were subject to attorney-client privilege.

Ensign said he messaged officials at the State Department and Department of Homeland Security as well as the Department of Justice, believing the judge’s orders “would be circulated to the relevant people.”

“Who made the decision” to continue with the flights, Boasberg asked.

“I don’t know,” Ensign replied.

“You really don't know? I’m interested in finding that out,” Boasberg said.

“If I find there’s probable cause for contempt ... then there’s a good chance we’ll have hearings,” he added. “I will review the material and issue an order and I will determine if I have found that probable cause exists to believe that contempt has occurred, and if so, how to proceed from there.”

The judge also noted the case of a wrongly deported Salvadoran man, who was among dozens of immigrants on planes bound for El Salvador, to suggest that the administration rushed their removal to evade the court’s scrutiny.

Boasberg also noted eight women and one Nicaraguan man were returned to the United States after the Salvadoran government refused them, arguing that the Trump administration operationally could have brought people back if it wanted to.

The Trump administration is also refusing to answer questions about the flights under a “state secrets privilege” to prevent the release of evidence that could compromise national security. Ensign said the State Department fears “diplomatic consequences.”

Flights were in the air on March 15 when Boasberg ordered the administration to turn the planes around after a lawsuit from the ACLU challenging their clients’ removal. The judge wants to know when government lawyers relayed his verbal and written orders to administration officials and who, if anyone, gave the flights a greenlight despite the orders.

While Boasberg is weighing the possibility of sanctions against the administration, government lawyers are calling on the Supreme Court to allow Trump to resume removing immigrants from the United States under the Alien Enemies Act, a centuries-old wartime law invoked for the fourth time in U.S. history to target alleged member of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

“This case presents fundamental questions about who decides how to conduct sensitive national-security-related operations in this country,” according to the administration’s filing with the nation’s highest court last week.

“The Constitution supplies a clear answer: the President. The republic cannot afford a different choice,” the petition states.

The request follows a federal appeals court’s rejection of the president’s attempt to throw out Boasberg’s ruling that is temporarily blocking the administration from deporting immigrants under the act.

Trump’s proclamation states that “all Venezuelan citizens 14 years of age or older who are members of [Tren de Aragua], are within the United States, and are not actually naturalized or lawful permanent residents of the United States are liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as Alien Enemies.”

But the administration has since admitted in court filings that “many” of the people sent to El Salvador did not have criminal records, and attorneys and family members say their clients and relatives — some of whom were in the country with legal permission and have upcoming court hearings on their asylum claims — have nothing to do with Tren de Aragua.