A judge in Oklahoma has allowed a lawsuit seeking reparations for the survivors and descendants of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre to move forward, marking a victory for the plaintiffs and legal team that have pressed the case for justice following the century-old attack and its grim shadow.

Judge Caroline Wall dismissed a motion for the case to be dismissed in part on 2 May, allowing the case to proceed, though it remains unclear what will happen next and whether it will advance to a trial.

The lawsuit was filed last year ahead of the 100th anniversary of the two-day attack in the once-thriving Black neighbourhood of Greenwood, during which a white mob supported by law enforcement and city officials killed as many as 300 people and left thousands of Black residents homeless in one of the nation’s bloodiest episodes of racist violence in the 20th century.

It was also one in which no one was ever charged with a crime; Oklahoma high school students were not required to learn about it until 2019.

The lawsuit aims to correct the record about the deadly events on 31 May, 1921 and create a fund for survivors and their descendants.

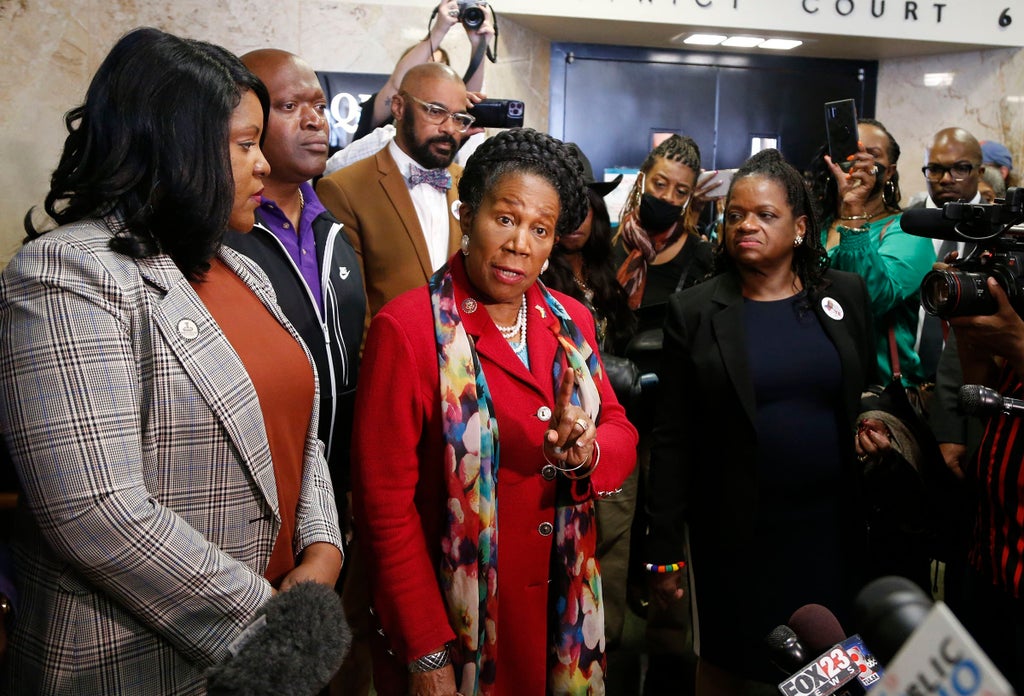

Three known survivors – Viola Fletcher, Hughes Van Ellis and Lessie Benningfield “Mother” Randle, who were all small children during the attack and are now plaintiffs in the case – testified to Congress last year to discuss the massacre’s racist legacy and call for justice for the families and communities in its wake.

The lawsuit led by Tulsa-based civil rights attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons invokes the state’s public nuisance law; the city, state and insurance companies failed to compensate victims and actively impeded their recovery, plaintiffs allege.

It names the Tulsa County Board of County Commissioners, Tulsa Metropolitan Area Planning Commission, Tulsa County Sheriff and the Oklahoma Military Department, among others, as defendants, which have repeatedly sought to dismiss the case.

“I’ve seen so many survivors die in my 20-plus years working on this issue. I just don’t want to see the last three die without justice,” he said following the court’s decision. “That’s why the time is of the essence.”

A 2001 commission tasked with investigating the massacre said the mob “set fire to practically every building in the African American community, including a dozen churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drug stores, eight doctor’s offices, more than two dozen grocery stores, and the Black public library.”

By the 1960s, Greenwood was beginning to get back on its feet, with Black businesses opening throughout its 35 blocks.

But the long road to recovery would suffer the same systemic impacts of racial violence that reverberated across the US throughout the 20th century, from redlining and construction of highways through Black neighbourhoods to “urban renewal” initiatives and the use of eminent domain to seize Black-owned property.