Little more than 10 years ago, the Parisian photographer JR was what’s usually called a vandal. He pasted things illegally in the street. Did you have a revelation at some stage, I ask him, when you thought, “Ah, this is art”?

“No. At the time, there was not street art,” he says. “There was no Banksy. It’s not the kind of thing you said you wanted to be when you’re older.”

What? A criminal?

“Exactly.”

JR still pastes things in the street; it’s just that the things have got bigger. And the world has an expanded idea of what’s vandalism and what’s art. JR’s canvases are now tower blocks, whole buildings, entire streets. His scale is epic, monumental. He turned the separation wall between Israel and Palestine into a giant gallery of faces – Palestinians on the Israeli side, Israelis on the Palestinian side, though no one could tell. He transformed a huge favela in Brazil into a vast artwork in which he literally gave the town eyes, and he displayed a pregnant refugee on the point of giving birth on half a mile of the Seine embankment in the solidly bourgeois Ile Saint-Louis.

He’s usually described as a street artist and given that he’s from Paris, and started out spray-painting walls and has the semi-anonymity of those two initials (his real name has never been made public), “the French Banksy” is a description that tends to follow him around. But whereas Banksy is furtive, stealthy, inward, JR couldn’t be more expansive. He works with a large team of people across two continents, collaborates constantly, and communicates – via Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat and the walls of dozens of cities around the world – relentlessly.

He has a knack for making the invisible – people, usually, the poor, the marginalised, the forgotten – visible. It’s a sort of magic trick, I realise, making people appear, making us take notice, although it’s David Blaine, the American street magician, who is actually the one who points this out to me. Blaine is known for his feats of endurance that exist somewhere at the edge of art and magic and madness – he once spent 44 days in a Plexiglass box suspended above the Thames – and he’s a friend of JR’s.

“JR sees things from a different perspective,” Blaine tells me. “He pasted this figure of a person, hundreds of metres long, on the sidewalk at Fifth Avenue and Madison and everybody was walking over it and nobody saw it until it was photographed from above. It was completely invisible but suddenly seen by everyone. The way he’s using his art has made me think about magic in a very deep and personal way.”

When I meet JR, it’s just a few weeks since Europe’s refugee crisis has finally hit the top of the political agenda propelled by the heartbreaking image of a small dead boy on a beach. And it strikes me that it’s a real-life example of exactly what JR has spent the past 10 years trying to do. It’s all about trying to get people to take notice of the people we spend most of our lives failing to see, or maybe, more accurately, trying to avoid seeing. JR’s work has been to find a strange angle or a previously hidden corner and bring them to us. He shows us them at massive scale, or across landscapes, or just in some new or surprising or beautiful way we weren’t expecting.

JR used to be one of those people. A banlieue kid. Half Arab – his father is Tunisian – he grew up on the wrong side of the Périphérique, the ring-road that separates the bourgeois quartiers of central Paris from the places where it houses its large immigrant population: in huge concrete cités or public housing projects. It was in one of these, Les Bosquets, that JR came to take photographs 12 years ago and set in train the sequence of events that’s led him to where he is today.

It was in the same suburb that the riots kicked off exactly a decade ago, the riots that swept through the banlieues and then the rest of France over a period of weeks and saw running battles with the police and more than 10,000 vehicles destroyed. And when I meet him, he’s back in the neighbourhood with a film called Les Bosquets. Even by JR’s standards, the project is a stretch. As a concept, it’s bordering on hallucinatory: a classical ballet performed in a housing estate reimagining the events of the 2005 riots. It’s just 17 minutes long and, in the blasted concrete wastelands, mixes first-hand video footage of the riots with ballet and modern street dance he has choreographed himself.

It is as extraordinary as it sounds and yet it’s a tiny fragment of his work in progress. I have a massive paving slab of a book in my bag, a retrospective of his work published this month by Phaidon, and the shoulder-sagging weight of it is a testament to the super-sized nature of almost everything to do with JR’s output: the breakneck pace of it, the sheer number of projects he’s done, the global reach of his ambition.

“And he’s how old?” Emmanuel Perrotin, his Parisian gallerist, asks me. “He’s what? 32? The evolution of his career is astonishing for his age.” Perrotin gave Damien Hirst his first commercial show and though JR is most often compared to Banksy, he says he sees greater parallels with Hirst. “I was in Shanghai in a car driving very fast and in the landscape I saw a water tower with an old woman’s face on it and was like, ‘Whoa!’ I recognised it immediately as a JR even when I had no idea he had ever done anything in this city. That was the moment I thought differently about him.”

I meet JR on the eve of a major show in Perrotin’s gallery and he’s in the final editing throes of another short film about Ellis Island – called Ellis – another tiny, no-budget art film that just happens to have Robert De Niro in the starring role. And every time I look at his Instagram feed – he’s embraced technology and is one of the most popular artists on the platform with 679,000 followers – I find another arresting image. This week: a huge pair of eyes staring out of a pedestrian bridge in Toronto. Days earlier, a portrait of an immigrant called Ibrahim pasted across 50 storeys of a building in Philadelphia. Last week, a huge solitary man several hundred metres up a skyscraper in Boston.

“He is pure energy,” says Perrotin. “The amount he does… that he’s doing… it is really incredible.”

It’s telling that Shepard Fairey – the street artist who produced Obama’s campaign posters – has called JR the most ambitious artist he’s ever met. It’s just that with most artists – or anybody, actually – that would be code for an ego of unprecedented proportions. And yet, almost all of JR’s work is to do with other people. It’s about making their faces seen, making their voices heard.

“I’ve never known him reluctant to meet anybody,” says David Blaine. “His curiosity is not one-sided. He likes interacting with people. Talking to them, seeing their reactions.”

He’s not kidding. At the premiere of Les Bosquets, he hops around afterwards, talking to everyone with a friendly informality, a lean, wiry figure who seems to have more energy than he knows what to do with. He’s in his trademark hat and sunglasses. He uses semi-anonymity – he always wears the hat and glasses in public – but it’s for practical reasons he says. He doesn’t want to be recognised in the streets or have problems getting into countries where they don’t want him.

It’s a deeply incongruous film, Les Bosquets. The crowd, an audience mostly of invited locals many of whom starred in it as extras, applaud wildly at the end. Gorgeous dancers in pristine white silk tutus are interspersed with graphic scenes of the riots and in this, it’s as good a showcase for the JR method as anything: an outrageous idea, flawlessly executed with the help of a huge cast of collaborators, in this instance classically trained ballet dancers from the Paris Opera and one of the most successful songwriters du jour, Pharrell Williams: he’s another friend, it turns out.

“I had this footage of this building being demolished and I wanted some music to go with it and I asked Pharrell, can you write something for it. And he was the one who said, ‘Why don’t you make something bigger?’”

It is bigger. It may only be 17 minutes long and yet it is by turns thrilling and terrifying and touching with the kind of wildly dramatic score you’d have in a high-concept Hollywood movie, hardly a coincidence because Pharrell persuaded Hans Zimmer, an Oscar and multi-Grammy award winner who has scored many Hollywood blockbusters, such as The Lion King, the Pirates of the Caribbean series and The Da Vinci Code, to get involved. But then, JR seems to have a number of collaborators practically queuing up to work with him. As well as Robert De Niro, I spot on his Instagram feed Darren Aronofsky, Spike Jonze, David O Russell and Sacha Baron Cohen. There are projects afoot but he’s keeping his cards close to his chest.

Your film-making is a dream, I say. I don’t think this is how it normally works, that Oscar winners line up to offer their services for nothing?

“It’s because everything is non-commercial,” he says. “There’s no producer or money or anything. There’s not even any guarantee that anyone will see it as he’s deliberately not releasing his work online. “It’s too easy today to just watch something on your phone, alone, on the train,” he says. He wants people to gather. “It marks them and creates something that they will remember.”

There’s a purity to everything JR does. He finances everything himself. He refuses to work with brands or institutions. He’s taken a stance against the dominant visual culture of our lives: advertising. In most cities, they’re the only images the size of JR’s artworks and they’re selling cars or underpants or perfume. JR replaces products with people. He’s returning the city to its people.

He won the TED prize ($100,000 to be spent on a “wish to change the world”) in 2011, which gave rise to the launch of his biggest project to date, Inside Out – the ultimate expression of that principle. He wanted people everywhere to take back their towns, their cities, their streets. Upload a photo on insideoutproject.net and his team will create a poster-sized print and send it to you free, wherever you are. More than 100,000 have now been pasted in more than 140 countries so far and the project is ongoing.

It could have been the world’s biggest selfie-fest but the best of them – in Tunisia, for example, where after the revolution the presidential palace was graphically returned to the people with their faces in every window – are beautiful and moving. Humans are at the centre of everything that JR does and their photographs are as fascinating and varied and emotional as humans are.

The project, however, has been “a hole where money disappears”, he says. Hundreds of people – the CEOs and billionaires at TED – offered to help finance it initially, “but they were like, ‘OK, we’ll give you 10 cars if we can put our logo on it. And I was like, ‘No just do it for the kids. Just do it to do it.’ And none of them wanted to. In the end, there were maybe five or six who really helped. But the rest, they wanted their logo on something.”

Are you in something of a war against brands? “Not a war. I just don’t like it when they take over public spaces… I remember when we were in the Middle East, people would ask us, ‘Who’s financing this?’ And I was like, ‘No one. Are you kidding?’ And they said, ‘It’s so big that we assumed it had to be an oil company or something.’”

Over time, he says, he’s tried to remove himself from his work entirely. “In Brazil [the favela project], I left the country and let the people speak for it. It was so much more interesting than whatever I could say. My whole world has been how can I keep a distance from it. Until I said, ‘Look, I’m not even going to go there. People are going to paste that photo without me and not even credit where it comes from.’ That’s our Inside Out project. They were pasting in Haiti, in Pakistan. I’ve never even been to Pakistan.”

He understands the need for people to be seen, because he felt it so strongly himself. “I started in graffiti, where you write your own name. I was coming from that egocentric thing where you go and say, ‘Hey I’m JR’. I really understand that mentality of wanting to exist in a city that’s full of advertising and code. But once I started taking other people’s photos, and especially, at that moment, pasting them, when I realised that I was giving them a voice, I realised that was so much more powerful.”

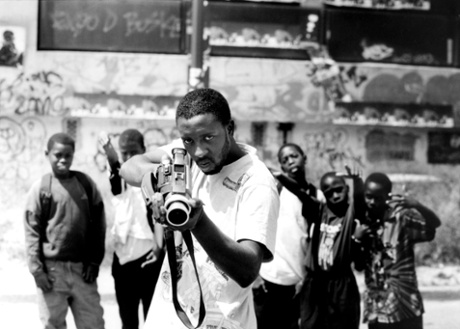

That was the lesson he learned in Les Bosquets 12 years ago. His friend Ladj Ly, who was experimenting with video, took him to the banlieue where he grew up. “I had a camera with me and there were all these kids saying, ‘Why don’t you take our photo?’ It wasn’t even my camera. It was a friend’s family camera and it was [old-fashioned] film so you couldn’t see what you were taking photos of.” But there was a moment when Ladj raised his video camera like a gun. “And I took it, boom. And then I said, ‘Whoa, let’s do it again.’ But the kids had run away and I never made it again. There was just a single shot. I went to a one-hour photo place and I knew immediately that I had something.”

Twelve years on, it’s still a powerful image, the camera Ladj’s weapon. JR knew he wanted to show it somewhere. “I thought somewhere in the centre first but then I looked around at all the broken buildings, completely full of graffiti, and I thought that’s where it should be. That’s where it makes most sense. I wanted to make it big but I didn’t know how. Eventually I found a printer that did architect plans and got him to print strips of black ink. It was all new, learning how to do it.”

Pasting it took four nights. “The police would come but we got the kids to hang out at the bottom of the ladder.”

It might have all ended there but two years later when Paris burned, that photo of Ladj, huge and menacing, became a backdrop to the violence. “It was really weird because suddenly that image took on a completely different meaning. It was there on the news with fires burning in front of it.” The media coverage of the riots was a huge part of the story. “It was quiet every night at 8pm because everyone was inside watching themselves on the news”; the kids he knew “being portrayed like animals”.

They were being filmed with long lenses from a distance. “It was the first time I questioned the distance,” he says. His response was to take a tiny camera and shoot the kids in extreme closeup. He got them to act out the caricatures that they thought they were being portrayed as. And then he pasted them, super-sized, in the banlieue, but also in the centre of Paris. “I put their name, age, even their building number. Because from Paris, it looked like they were an army that was about to invade.”

Since then, Ladj’s photo, several hundred metres high, has been pasted across the outside of Tate Modern and the sense of mission that JR developed then has driven all his work since. The surburbs, he says, are the city, inside out. And it’s Ladj who provides the voiceover in the film Les Bosquets. “At the time, I needed the attention to prove that I existed,” he says. “It made me feel a little bit better.”

I speak to Ladj later and he tells me what JR was like then (“full of energy, always doing stuff”) and he mentions that he still lives in Les Bosquets. Why? I ask him. “C’est la lutte de ma vie,” he says. “It’s the fight of my life.”

JR now lives in New York but it still feels like he’s in the fight of his life too. And while he has acquired new, famous collaborators, he still works with the same gang he had back in the suburbs. He has a studio in Paris and one in New York and it’s full of people he’s known for years.

“I’ve known them for ever so it’s like we’re one big family,” he says. “It’s fun. Anywhere I go I feel like I’m home in a way, since I’m with friends and people I know. That’s one thing that’s really important when working with a team – that it’s the same team.”

Emile Abinal, the head of his Paris studio, tells me how he met JR when he was still an art student. “The first time I saw his stuff in the street, I was just like ‘Wow!’ It was completely new and different. I used to tear them down and keep them. He did these photographs with big spray-painted frames that he called ‘Expo de Rue’ [street exhibition].”

They became friends and Emile eventually started working with him full-time. “It’s always changing,” he says now. “It’s probably why we are all so loyal. There’s always something new. He has an incredible energy, like you can’t imagine. He doesn’t drink or smoke. He gives all his energy to his work. To interacting with people. He’s always focused on his art. It’s his way of living.”

He tells me about some of their escapades in Liberia, including an incident where they found themselves at the mercy of a bunch of kids with guns. “But JR just talked and talked with them. He has a way of communicating with people.”

François Hébel, former director of the Arles photo festival and the Magnum photo agency, also met JR early on, when he came across him pasting outside an official photography exhibition. “I looked out the doorway and I saw him across the way up a ladder, pasting these little contact strips. He was very young but there was something about it. It was surprisingly mature.” A few years later, Hébel was one of the first to bring JR inside the art fold with a prestigious show at Arles. He says it’s been astonishing to watch his career progress.

“He’s constantly changing. He’s building, building, building. Every project, he’s another step ahead. It’s very frustrating to me because I can’t see how he can just step into something completely new like ballet but that’s exactly what he does. We used to have these arguments. I’d say, ‘It’s very political what you’re doing.’ And he’d say, ‘It’s got nothing to do with politics!’ And I’d say, ‘Of course it has.’ Whatever he has done, it’s the new politics, it’s direct action.”

It is and he’s right at the edge of one of the biggest contemporary debates: who belongs? Who matters? He made a huge installation of old photographs of 19th-century immigrants to New York inside the crumbling immigration buildings of Ellis Island, which led to the film Ellis, and lately he’s been pasting photographs of more recent immigrants on cityscapes across America. And then there’s the container ship that he turned into a massive world-circumnavigating artwork (the containers are his “pixels”) that ended up rescuing a boatload of immigrants from Libya who were drifting helplessly off Greece.

Indeed, there’s a random, happenstance quality to almost everything JR does. One thing leads to another. One person leads to another. How did he even have the idea of bringing the ballet dancers to the banlieue, I ask him.

“I’d just finished choreographing a ballet for New York City Ballet…”

But how did he even come to do a ballet in the first place?

There follows a rambling and slightly fantastical explanation of how he came to do a full-scale ballet about the French riots with the New York City Ballet, one of the leading companies in the world, not ever having seen a ballet until that point. But then everything with JR seems to have a rambling and slightly fantastical explanation.

“There’s no goal as such,” he says. “Like, even now, I couldn’t tell you what I’ll do next year. Even last year I couldn’t tell you that I was going to do a ballet. I love not knowing. The question people always ask me is, ‘What’s next?’ It’s really scary when you work like that. There could be nothing next. But I like being able to change direction at any time.”

So, what’s next? “I don’t know! I’m in a faultline. I’m at risk. There could be nothing next.”

There could be. But I doubt it.

JR: Can Art Change the World is published by Phaidon (£39.95). Click here to buy it for £27.97. An exhibition, JR: Crossing, which includes screenings of Ellis, is at Lazarides Rathbone, London W1, from Friday until 12 November. Inside Out, a documentary about JR, is available on iTunes