London’s National Portrait Gallery is gradually returning to life. After a three-year, £44mn refurbishment, builders have completed the main sections of its 1896 building off Trafalgar Square and the paintings are being rehung in preparation for its reopening in June. I walk past portraits of Tudor kings and queens to Room 16, where an official in a hard hat unlocks the panelled doors.

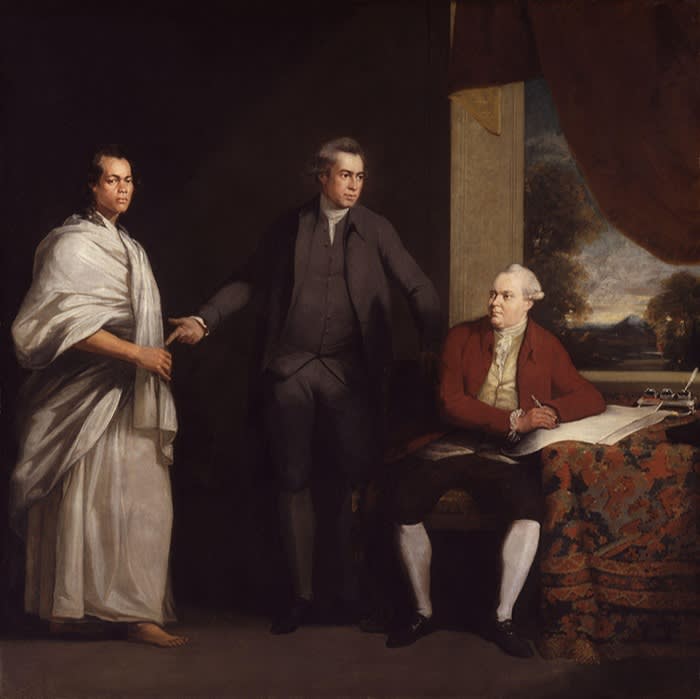

A single painting hangs inside, its faded gilt frame bearing a plaque reading “Sir Joshua Reynolds”. It is Reynolds’ “Portrait of Omai”, or “Omiah” as it was called when displayed at the Royal Academy of Arts’ annual exhibition in 1776, the year America declared independence. Neither is quite right, for the true name of the Polynesian islander who sailed to Britain was Mai.

It is a rare privilege to view the life-size portrait, now regarded as the greatest work by perhaps England’s finest portrait painter, although he had an 18th-century rival in Thomas Gainsborough. It has spent most of its time hidden since Reynolds displayed it to visitors to his studio a five-minute walk away in Leicester Square. But it is only here temporarily and may soon disappear again if the NPG cannot raise £50mn to secure it.

The portrait is magnificent and it somehow gains in power the longer I spend with it. Mai stands barefoot in flowing white robes and turban, one tattooed hand on a tapa cloth sash made from bark, the other gesturing forward against an Arcadian landscape. He gazes out confidently, half Pacific potentate, half “noble savage” of the 18th-century European imagination, a person supposedly uncorrupted by civilisation.

I look on with Nicholas Cullinan, NPG director, who two years ago heard that the painting’s owner for the past two decades, the billionaire Irish business magnate John Magnier, wanted to sell it. Cullinan talks of his “instinct” that, despite the intimidating price tag, the work had to be kept in the UK on public display, not acquired by a US museum, or sold to a private collector.

More is at stake than one painting. Tate, the family of four public galleries across the UK, has about 45 Reynolds works in its collection, and other 18th-century portraits hang in British museums. But many are of lords and ladies, naval officers and merchants, and very few are of people of colour. The National Gallery of Canada owns one of the best-known examples: Gainsborough’s 1768 portrait of the former slave and abolitionist Ignatius Sancho. “Portrait of Omai” would start to redress that national failure.

The portrait, and Mai’s story, could help Britain “to examine our past and understand who we are as a nation,” leading historians wrote to the FT last year. Cullinan recalls talking to the black British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, who has just had a solo show at Tate Britain, about journeys she took by bus when young to visit the NPG. “This would be an extraordinary thing for us to have and everyone to share,” he says.

But the struggle to raise £50mn reflects a painful truth about Britain’s financial state. “Europe has a great deal of art, and America has a great deal of money,” said Joseph Duveen, the legendary art dealer who in the early 20th century sold many Old Masters in Britain to US millionaires. As prices at the top of the art market rise, just how many paintings can a cash-strapped nation hope to keep? And will it need to rethink how it saves them?

It would have huge resonance if the NPG triumphs. “This work has a unique history with this country. It’s always been here and we can’t let it go without a fight,” says Cullinan. But until recently, the museum had only about half the money it needs. Unless that changes soon, I may be among the last to view Reynolds’ masterpiece in the city to which a young Polynesian once sailed.

Mai was born in the middle of the 18th century at the heart of the Polynesian universe. When the creator god Ta’aroa broke out of his shell and formed heaven and earth, Polynesians believed that he made all the other gods and the Society Islands around Tahiti. Mai’s island of Raiatea, with its coral reef and green hills thrusting out of the Pacific Ocean, was the holiest, home to the sacred temples of Taputapuatea.

Mai was not one of the Raiatea elite, the chiefs who were its political and religious leaders, nor was he a commoner. His family was in the middle rank of administrators and advisers to the chiefs: a kind of Raiatean civil service. It was a stable upbringing, and being Raiatean brought him special respect on the other Society Islands.

Mai could have had a good life without leaving the island. He was charming and adaptable, making friends easily (“He is lively and intelligent, and seems so open and frank-hearted,” the novelist Fanny Burney later wrote). But his chance vanished when his home was invaded by islanders from neighbouring Bora Bora. His father was killed and the family fled by boat to Tahiti.

It gave him a life-long yearning to recapture his island from the Bora Borans, whom the Raiateans despised as pirates and “incorrigible blockheads” from a barren island, according to the Australian historian Kate Fullagar in her book on Mai and Reynolds. He meanwhile lived in Tahiti, assisting Tupaia, one of Raiatea’s leaders of the worship of ‘Oro, god of war and fertility.

In 1767, when Mai was in his teens, a second ocean incursion revolutionised his life: the British ship the Dolphin, captained by Samuel Wallis, sailed into Matavai Bay in Tahiti on its voyage of discovery. Britain was then an imperial superpower, with conquests from America to India, but while it had one eye on beating its recent enemy France to trade routes, Wallis was primarily there to explore.

The encounter did not go smoothly at first. When the islanders paddled out in canoes to exchange goods, the Dolphin fired its cannons and Mai was among the wounded. But he recovered, Tupaia helped to broker a truce and things settled down amid feasting. When they returned home, the English visitors, including a young officer called Tobias Furneaux, brought with them stories of a Tahitian utopia that set off a “Pacific craze” in Britain.

“There was a sense of shock, excitement and curiosity about these ‘new people’ in the Pacific. A lot of that was reciprocated by Polynesians, who saw people from beyond the known universe who possessed extraordinary things such as guns, and were clearly bearers of power,” says Nicholas Thomas, director of Cambridge university’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

HMS Endeavour, captained by James Cook, followed the Dolphin two years later. Cook’s Tahiti voyage was a joint expedition of the Navy and Royal Society in London, carrying scientists such as Joseph Banks and the Swedish botanist Daniel Solander. When Cook sailed on to claim New Zealand and Australia, Tupaia went with him, but died in Indonesia of disease.

Mai got his own chance in 1773, when Cook returned to Tahiti on his second voyage with the ships Resolution and Adventure. Mai persuaded Furneaux, by then captain of the Adventure, to take him when they returned and he was still on board the following year when it docked in England.

The idea of a Polynesian visitor to Georgian London was not as strange as it might sound. The historian David Olusoga notes in his book Black and British that Britain’s leading role in the slave trade meant “black Georgians were everywhere” in London, working as servants, coachmen and pageboys. Some 15,000 black people were estimated to live in the city in 1772, and both Reynolds and his friend, the literary wit Samuel Johnson, had black servants.

Mai himself was part of a second phenomenon, known as the “savage visit”. The explorer George Cartwright brought five Inuits from Labrador to London in 1772, and non-European visitors were often treated as envoys, going back to the arrival of the Algonquian princess Pocahontas in 1616. This was not simply courtesy, but a matter of trade and territorial interest. “The British knew if they wanted to control Tahiti one day, a treaty would need to be signed,” says Fullagar.

The Earl of Sandwich became Mai’s sponsor for the visit, along with Banks and Solander, the scientists from the Endeavour, and he was invited to stay in Banks’s house in Mayfair. He was soon presented to King George III at Kew Palace, after being fitted for a velvet coat, white waistcoat and satin breeches. The King gave him a sword and arranged for his inoculation against smallpox, of which several of the visitors from Labrador had died.

London society relied on intricate rituals, but Mai was versed in them from Polynesia. “He walks erect, and has acquired a tolerably genteel bow, and other expressions of civility,” wrote a Suffolk parson after meeting Mai at the Royal Society, where he dined 10 times during his two-year stay, and was signed into the visitors book as “Mr Omai” (the name was a misunderstanding: “Omai” meant “It is Mai” or “from the family of Mai” in Tahitian).

The Duchess of Gloucester threw him a party, to which he wore Tahitian robes; he went to performances at Drury Lane and Sadler’s Wells; he attended the state opening of Parliament; he visited the north of England, he went shooting and swum off Scarborough beach; he learnt to ride and play chess; he moved into lodgings in Soho and paid social calls.

But Mai never forgot why he was in Britain, and told anyone who was willing to listen. “Omai says he wants to return with men and guns in a ship to drive the Bola Bola [sic] usurpers from his property,” recorded Banks’s housekeeper. That message tended to be ignored amid the curiosity over a man who neatly fulfilled the Enlightenment notion of the “noble savage”.

“Everybody [remarked on] the savage’s good breeding and the European’s impatient spirit,” wrote one socialite when Mai beat the literary critic Giuseppe Baretti at chess. Fanny Burney, who knew Mai through her brother James Burney, an officer on the Resolution, was charmed: “He is so polite, attentive and easy, that you would have thought he came from some foreign court.”

By the end of 1775, Mai was moving fluidly through London society. He was bound to bump into Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Britain was in flux in the 18th century, vaulting out of an agrarian society into a country of wealth, powered by the industrial revolution and imperialism. Aristocrats were being jostled by an emerging class of upstarts, from naval officers to merchants and squires. “Wealth, howsoever got, in England makes/Lords of mechanics, gentlemen of rakes,” wrote the novelist Daniel Defoe.

What better way to cement your new status than having your portrait painted, and who better for the task than Joshua Reynolds, first president of the Royal Academy of Arts? Reynolds’ “grand manner” portraits of the elite were proof of having arrived. From his 1752 portrayal of the naval captain Augustus Keppel striding clear of a storm, he projected noble purpose on his subjects.

“Reynolds was an incredible entrepreneur,” says Lucy Peltz, senior curator of 18th-century art at the NPG. “He really knew how to milk the system for his benefit and carried a pantheon of other artists with him . . . He invented the modern world of art.” When he started, portrait painters were scorned as hacks; by the time of his death, they were august figures.

Born in 1723 to a clergyman and schoolmaster, Reynolds was as middle class as Mai. But after apprenticing with a painter and spending two years in Rome, he set up on his own in London. Like Mai, he glided through the upper echelons of society, befriending figures such as Samuel Johnson, the statesman Edmund Burke and the actor David Garrick.

Reynolds was everywhere, accompanied by the ear trumpet he carried after going partially deaf while abroad. “His pencil was striking, resistless, and grand/His manners were gentle, complying and bland,” the playwright Oliver Goldsmith wrote tartly. By the 1770s, people were lining up to pay his high fees and be painted in his octagonal studio in Leicester Square.

He mostly worked to commission, but sometimes chose sitters who inspired him. Mai offered the chance to create something exceptional. The true painter must “endeavour to improve [society] by the grandeur of his ideas . . . he must strive for fame by captivating the imagination,” Reynolds once declared. Perhaps he also felt the chill of younger competition: Gainsborough had moved his studio to London in 1774.

Reynolds took the task seriously, making sketches of Mai in both pencil and oils. For the portrait, he showed Mai in a heroic “Apollo Belvedere” pose taken from a Roman statue. He also sprung a visual surprise, using lighter shades rather than the Baroque dark of other portraits: it shone out in the Academy’s candlelight. A “strong likeness and finely painted,” The Morning Post declared.

Reynolds never let the painting go, keeping it at his studio until his death in 1792, years after Mai himself had returned home. A dealer bought it from Reynolds’ estate for 100 guineas (about £16,000 today) and passed it on to Frederick Howard, Earl of Carlisle. Then it hung in Castle Howard, the family’s stately home in North Yorkshire, for most of the next two centuries, surviving a fire in 1940 that damaged two Tintorettos.

Time only made it more exceptional. Reynolds was a restless innovator and fashioned the rich glow of some of his portraits by mixing bitumen into their pigments. But as decades passed, those portraits blackened and cracked. “Omai” was unscathed, the young voyager’s face as fresh as the day it was painted.

When Henry Huntington, the Californian railway magnate, sailed the Atlantic with his wife Arabella on the Aquitania in 1921, the couple stayed in the Gainsborough Suite. The British art dealer Joseph Duveen was also on the voyage and one night at dinner, the Huntingtons saw and admired a reproduction of “The Blue Boy”, Gainsborough’s 1770 grand manner portrait of a young man in Van Dyck dress.

As soon as they reached London, Duveen hustled across town to see its owner, the Duke of Westminster, and persuade him to sell it, together with a Reynolds portrait of the actress Sarah Siddons. Duveen did not have to pitch too hard: the duke needed money and the Huntingtons had it. But there was national anguish when “The Blue Boy” departed for America the following year.

“Absurdly enough, perhaps, one or two of us had tears in our eyes, we hardly knew why. Perhaps it was because some of the lovely youth of our country seemed to be going with him,” mourned an article in The Times. The deaths of millions in the first world war were still painful, and there was a sense of a loss of status as the US overtook Europe economically.

It took decades for “Omai” to face a similar squeeze, but in 2001, the Howard family offered the portrait for sale to Tate to clear inheritance tax debts. Nicholas Serota, Tate director at the time, tried to agree a private treaty purchase, with funding from a National Lottery-backed heritage fund.

He failed when the fund would not back a raised bid, setting off a wrangle that endures to this day about who owns “Portrait of Omai” and what it is worth. Tate could have secured it for about £6mn and Serota, now chair of Arts Council England, regrets it still: “I felt we lost over a quarter of a million difference. Look at the price now.”

“Omai” found its next owner on a rainy day in November that year at Sotheby’s auctioneers in London. Henry Wyndham, of the art adviser Clore Wyndham, was then chair of Sotheby’s in Europe and oversaw the sale. “I don’t think it took more than four or five minutes,” he recalls. When he brought down the hammer, “Omai” went to a dealer for £10.3mn, beating its £6mn-£8mn estimate.

The client turned out to be a Swiss fund controlled by John Magnier, owner of the racehorse breeding operation Coolmore Stud and one of Ireland’s wealthiest men. Magnier’s wife Susan was an art collector and they later added Modigliani’s “Nu couché” to their collection for $26.9mn, reselling that work at Sotheby’s in 2018 for $157.2mn. Magnier has never explained why he acquired “Portrait of Omai”, and declined to comment for this article.

What is clear is that Magnier is an astute investor, especially in assets that come with tax advantages. The highly profitable racehorse breeding industry in Ireland was built on a tax exemption for stallion fees devised by the former Irish premier Charles Haughey in 1968. Magnier took over the Coolmore Stud in Tipperary with partners in 1975 and turned it into a global success.

Magnier soon collided with Tate. He applied to export the portrait in May 2002 but the government imposed an export ban until the following year to give the museum another chance to buy it. The price had already risen to £12.5mn, and Serota launched a public campaign, enlisting the naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough to spearhead the effort.

The two sides got along badly. Magnier did not appreciate being impeded and would not let “Omai” be publicly displayed for fundraising. Serota criticised his lack of co-operation, then made a public apology in an effort to mend relations. It failed to charm: when Tate found a private donor willing to buy “Omai” and lend it back to the gallery, Magnier refused to sell.

The UK government then blocked him from taking the portrait abroad, starting a tense 20-year stand-off between an Irish billionaire and the British establishment. “Omai” remained in storage at Christie’s until 2005, when Magnier let it be shown at a Tate Reynolds exhibition. In return, the government gave him a licence to lend it to Ireland’s National Gallery.

It might have been a public-spirited gesture, but it also came with a potential tax break. At the time, Irish residents who loaned paintings to the country’s public museums for six years could avoid capital gains tax. In 2012, “Omai” duly returned to storage, emerging briefly in 2018 for an exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Magnier has thus stretched to its limits Britain’s system for rescuing historic works, which was created in 1952 when a committee headed by the politician Lord Waverley drew up criteria for which works should be temporarily blocked from export to allow time for a British buyer to match the price. The idea was to stop a repetition of Duveen’s crafty siphoning of stately homes.

Amid all the controversy around “Omai”, nobody (including Magnier) has ever disputed that it meets all three Waverley criteria. It is closely connected with Britain’s history and national life; of outstanding aesthetic importance; and vitally significant to a field of art scholarship. The only issue is how much “Portrait of Omai” is worth. A committee of experts in art and cultural objects decides whether an object meets the criteria, and what is a fair price to pay. Last year, it mulled over the future of many objects, ranging from 17th-century Italian and French lute sheet music to Sheffield football club’s archive.

In June 2021, the committee reconvened to discuss “Portrait of Omai”, 19 years after Magnier first tried to export it for sale for £12.5mn. The billionaire had returned with a new price: £50mn.

Nicholas Cullinan is a precise man with a soft Yorkshire accent. He was born in Connecticut but his parents returned to Britain when he was four. His early interest in art from visiting galleries led him to study for a PhD at the Courtauld Institute of Art. That started a rapid curatorial rise through Tate Modern and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In 2015, he was appointed director of the NPG, where he had worked as an assistant while a student. At 37, he was not quite the youngest ever NPG director but came very close. As we sit in front of “Portrait of Omai” and he reels off reasons why it is an astonishing work and should stay in Britain, it is like listening to a fine-tuned engine at cruising speed.

Even so, Cullinan has sounded anxious in the past few months as he faces up to a monumental task. The gallery lacks deep pockets: it has an endowment of only £3.5mn, compared with the $8.6bn of the trust behind the world’s richest museum, the J Paul Getty in Los Angeles. It also started trying to raise the money amid a cost of living crisis and political turmoil.

“The whole timing has been deeply unfortunate because [the renewed export bar on ‘Omai’] was announced just as Russia invaded Ukraine,” Cullinan says. Last summer, it planned a public fundraising campaign similar to Tate’s 20 years ago, but then scaled back to appealing to its members and through Art Fund, a national charity founded in 1903 to help public museums acquire art. “We’re not asking people who are struggling to heat homes to pick this instead.”

This reticence has its critics. Lucy Ward, author of a biography of Thomas Dimsdale, the doctor who inoculated both Mai and Catherine the Great of Russia, has campaigned vigorously, collecting signatures for the FT letter last year. “I understand that handing round the begging bowl at a time of crisis is not a good look, but people will not give for something they don’t realise needs to be saved,” she says.

Sensing he might not be able to drum up the entire £50mn, Cullinan initially explored back-up plans, including a joint purchase of Omai with another museum. The Getty was the obvious international candidate; the family has given tens of millions to museums, including Britain’s National Gallery, and J Paul Getty II became a British citizen and was knighted before his death in 2003.

A cross-border acquisition and joint custody would be highly unusual, although not unique. The Netherlands and France jointly acquired two Rembrandt portraits for €160mn in 2015, and they alternate between the Rijksmuseum and the Louvre in Paris. The Getty responded positively to the idea of joining forces if the NPG needed a financial partner.

The prospect of “Omai” being moved back and forth between London and Los Angeles, perhaps every few years, raises many questions. But the Getty imprimatur would help to ease the biggest doubt that hangs over the enterprise: Is it really worth £50mn? Few question that it has doubled, or even tripled, in value in 20 years, but a fivefold jump?

The highest price paid for a Reynolds work at auction is the £10.3mn achieved by “Omai” itself in 2001. More often, they fetch much less: a 1778 three-quarter-length portrait of the society beauty Lucy Long, in a white dress with ribbons and pearls, was sold at Christie’s in 2016 for £3.8mn. Exceptional works fetch extraordinary prices, but “Omai” would be far out on its own.

Faced with Magnier’s gambit, the committee advised the government to appoint an independent valuer to assess the “unprecedented price”. Anthony Mould, an art dealer and expert in 18th-century painting, was handed the job and decided that the £50mn estimate was indeed justified. (He did not respond to my request for comment.)

Mould’s brother Philip is also a dealer in Old Masters, as well as an author and broadcaster. He believes “Omai” really could be worth £50mn. “The market for 18th-century art has been in decline, but flowing in the other direction, with far greater force, is the desire for diversity. It is hard to put a price on such a rare full-length portrait of a man of colour.”

Whatever “Omai” would fetch at auction, one thing is indisputable: the prices of top paintings are rising as more wealthy collectors compete. “The crux of the problem is that the graph is heading north, and both contemporary works and Old Masters are getting more expensive,” says Jenny Waldman, director of Art Fund.

This is especially awkward for the National Heritage Memorial Fund, a government-backed body launched in 1980 to rescue national treasures, which has to choose among paintings, rare objects and even dilapidated stately homes for support. “The sums for paintings are now on a different scale to decorative arts or property. You can save an unbelievable amount of coastline for £50mn,” says Sir Simon Thurley, chair of the fund.

Both the memorial fund and Art Fund dug deep when Cullinan asked, the former promising £10mn and the latter £2.5mn. More than 1,400 people have also made individual donations. But the gallery remains well shy of £50mn, with a deadline of March 10 approaching rapidly to raise the entire sum before the export bar is due to be lifted.

This makes Cullinan’s back-up plan to acquire the portrait jointly with the Getty more likely. The government is now considering a request from the NPG to extend the export bar until around June to give the gallery more time either to find last-minute donors or to agree a joint acquisition. (The US museum’s board would also need to approve a deal. It declined to comment.)

When Cullinan asked the memorial fund last year whether it would support the Getty proposal, it encouraged him to come back with a solo fundraising plan. Its role has always been to save treasures for the nation, not to half save them, and it said in December that a joint purchase of “Omai” would be a “low priority for . . . funding given that the painting wouldn’t be fully accessible to a UK audience.”

But the looming danger of losing “Omai” has had an impact. “We have been the greatest backers of this portrait all the way along,” Thurley told me this month. “If the NPG comes up with a novel and contentious way of saving it that is legally secure and the government supports, we want to see it.” (Magnier has this time committed to selling if the price is achieved.)

So the portrait may not be finished with making history. Apart from its unique subject and value, it is forcing a rethink of what saving national treasures means. Only a third of works put under temporary export bar end up staying in the country, and the UK’s arts minister Lord Stephen Parkinson recently suggested treating differently those “destined for public display [abroad] rather than private collection”.

Even if second best, “Omai” spending half of its time in Los Angeles would be better than being whisked away by another billionaire. The Getty does not charge for entry, and joint custody would set an international example to other museums to club together to keep great art on public display.

Mai did not have a happy return. After two years in London, he sailed with Cook on his third voyage in July 1776, after his portrait was painted. He was given a suit of armour and a chest of possessions, including some weapons, and Cook’s sailors built him a house on the island of Huahine, near Tahiti. But the British had no interest in helping him to recapture Raiatea, and he died about two years later.

Cullinan says that his own life was changed by seeing paintings in museums and “Portrait of Mai” could do the same for others, whether Londoners or visitors from far away. “This would be an incredibly empowering, beautiful, meaningful image to give people hope. I don’t think its power has yet been set free.”

If he succeeds, the painting of Mai will be carried from splendid isolation in Room 16 to the prime place in the NPG’s largest gallery, surrounded by many other portraits. There is a grand view through a succession of doorways, in which it would be framed. All of the kings and queens, lords and ladies, and 18th-century merchants would be made to gather round.

John Gapper is FT Weekend business columnist. For information on the ‘Portrait of Omai’ appeal, go to artfund.org/donate

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first