This story was originally published on April 6, 2022. It was included in a year-end list of SI’s best stories of 2022.

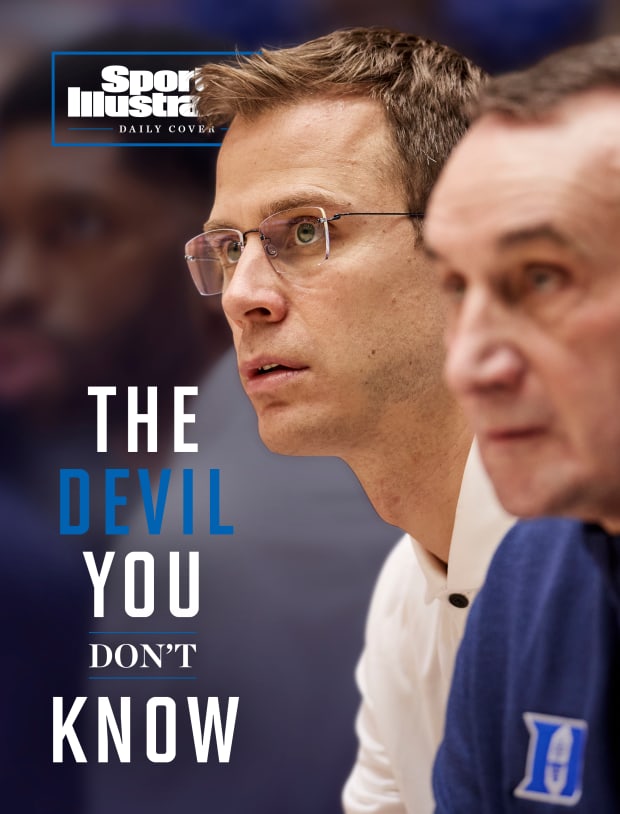

At 11:42 p.m. last Saturday, Duke’s head men’s basketball coach walked out of the locker room, and it wasn’t Mike Krzyzewski. Jon Scheyer, the guy after The Guy, went back to the team hotel, the Intercontinental in New Orleans, saw his family for a bit, and then headed to Krzyzewski’s room, where Coach K was recovering from the loss to North Carolina with his wife, Mickie, and daughter Debbie Savarino. “I just wanted to say thanks,” Scheyer explains. “We didn’t get too much into what’s next. He is so great at knowing what’s ahead, though. He just said he is there for me.” Then Scheyer went to his own room, where he did what head coaches do: not sleep.

Krzyzewski has assured Duke fans “We have a great succession plan,” and that may turn out to be true. But it’s a relatively new plan. One year ago, Scheyer interviewed for head-coaching jobs at UNLV and DePaul, and he and his wife, Marcelle, were just another young couple with small children imagining a new life for themselves. “He’s thinking about the job,” Marcelle says. And “I’m thinking about, Where will my kids go to school? Where are we living?” At various points, the Scheyers thought they would end up in Las Vegas or Chicago. At no point did they think they would end up here, with Jon ascending to K’s throne.

Duke athletic director Kevin White had told Scheyer that the only way to take over was if he became a head coach somewhere else first. Jon says now: “I was resigned to the fact that I wasn’t going to be the next coach at Duke.” Then UNLV and DePaul hired other coaches, White announced his retirement and Krzyzewski followed with his own. White was still Duke’s AD during the coaching search, but Krzyzewski and White’s replacement, Nina King, helped choose Scheyer.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

The Blue Devils’ new coach is only 34. He will be the youngest leader in the ACC by a decade. He has never been in a top job. Beyond an agent, he has never hired or fired anyone. Duke has gone from a coach who writes leadership books to one who reads them.

Scheyer will report to Coach K Court. Students will presumably still camp out in Krzyzewskiville. (Alternative: “Schey-town!” cracks the Chicago native. “We’re going to have one person.”) From a distance, replacing Krzyzewski seems impossible. Up close, it looks harder. Scheyer must fill more than Krzyzewski’s job. Somehow, he must also replace his presence.

On March 4, the night before Duke’s final home game, Krzyzewski addressed the Cameron Crazies with such cool charisma that Scheyer’s mother, Laury, texted Jon: “No pressure!” He responded with an exploding-head emoji. During the postgame ceremony the next night, Marcelle watched Krzyzewski with his family and had an “ugly cry” thinking about what he had built with them.

When Krzyzewski arrived on campus, in 1980, Duke had never won a national championship. He would go on to claim five. Yet Scheyer, a man of such ingrained optimism that he doesn’t even like to discuss the possibility of failing, says his goal is not just to match Krzyzewski’s record but to improve upon it. His dad, Jim, says, “He doesn’t see it as daunting.”

Yes, Scheyer is 34, but Krzyzewski was 33 when he took the Duke job, and Brad Stevens was 30 when he became Butler’s coach—and Scheyer has been planning for this a lot longer than Duke has. He has watched assistant coaches get head-coaching jobs without really planning on how to be a head coach. Scheyer started designing plays as a kid and never really stopped, but in recent years he has also thought hard about human behavior, about how successful organizations are built, about time management and media relations and what makes Duke great and what it could do better.

He has been a childhood phenom, a freshman starter, a sophomore coming off the bench, a captain, a national champion, a designated Hateable White Guy From Duke and a victim of a fluky, gory, devastating career-ending eye injury. He played under Krzyzewski for four years, worked under him for nine, and studied him for all of it.

Coach K won his first national championship in 1991; the next season, with basically his whole squad back and favored to repeat, he said his team was not defending a championship, it was pursuing another one. This is how Scheyer looks at the job. He is not just maintaining Krzyzewski’s program. He is building a new one on top of it.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Duke’s basketball offices will soon be under construction. Scheyer is open to renovating anything else in the program, too. He plans to tweak the offense in ways that he says will be noticeable. He has continued Duke’s recent philosophy of recruiting a new class of elite athletes every year, but Scheyer is increasing the emphasis on players who have a feel for the game like he did: passers, cutters, guys with court vision, who easily blend with others.

Smaller jobs have swallowed more established men. Scheyer’s success rests on two questions. How does he adapt Duke’s program to a rapidly changing environment while retaining what makes it great? And: How does he adapt his life to fit his new job, while retaining what makes him happy?

He must answer both to answer either. Otherwise, he will lose more than just games.

“I promised myself the day I got the job,” Scheyer says, “that I wouldn’t let it overtake me.”

Jon Scheyer had almost a year to prepare for his new job, but what seemed like a long runway felt more like a moving walkway. “All of a sudden,” Marcelle says on a warm Sunday morning in March as she sits on her family’s back deck in Durham, “it seems like it’s gone fast.”

Life changes have come tumbling at them. Jon was promoted; they decided to expand and enclose the aforementioned deck; they realized their house was still too small to host gatherings for the team and recruits, so they bought a larger house; Marcelle became pregnant with the couple’s third child, a boy, due in May; and their four-year-old daughter, Noa, announced recently that, over by the playset in the backyard, she married her daddy.

“I felt firsthand this year how efficient you have to be,” Scheyer says. “There’s no time to waste.” Asked whether his workload increased this last season in the wings, he says: “Yeah—not close. And next year will be more.”

His energy has always been abundant. Scheyer’s coach at Glenbrook North High, Dave Weber, says Scheyer was “competitive like I’ve never seen before,” and family and friends have stories to back this up. He would force himself to hit 40 straight free throws before leaving the gym … and if he missed the 40th, he would start over. He would outlast and outhustle anybody he knew at swimming-pool basketball. He got so angry about losing a video game that he broke a controller. “It’s the worst, losing to him,” says Marcelle. “I refuse to play Monopoly with him.”

Hearing this, Scheyer smiles.

In civilized society, this kind of extreme competitiveness is unusual. But at the highest level of sport, it is so common as to be cliché. Fierce competitor describes almost every coach who gets fired.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Being the head coach at Duke will not be a test of Scheyer’s desire. It will be a test of his ability to channel it. Losses will stick to him like they never did before—“in a real public way, too,” his mom says. Jon almost missed the birth of Noa, his first child, because Duke had a game that night, and he coached the first half while Marcelle was in labor. He regrets that now, but will he remember why he regrets it?

His sister Brooke says, “In the first few years of this job, I think, he’s going to come home and watch film until he’s blue in the face. That will be a learning process, managing the ebbs and flows of himself.”

His dad says, “I don’t know that we’re truly ready. The ups and downs are going to be stepping stones. I think that’ll be a little hard to remember early on, when it’s kind of white-hot.”

Reporters will ask questions that Jon might not think are fair, or that he doesn’t expect. Will he snap? Can he deftly sidestep controversy as well as Krzyzewski did when he doesn’t have all of that earned credibility or aura?

Scheyer: “The first time we lose a game—which, I don’t plan on losing, and I don't even like saying that’s going to happen, but I understand in the profession I’m not going undefeated for 40 years—[they’ll say]: ‘He’s the wrong hire, worst coach, doesn’t know what he’s doing, too young …’ I promise, I will not get caught up in that. But [Marcelle and I] have had to talk about it.”

He says Marcelle is “tough,” too. “She doesn’t really care what other people say.” But in time, Noa, Jett (who’s 2) and their third child will have questions, like why their parents never dressed them in baby blue, and why their father refuses to eat in any of the fine restaurants in Chapel Hill, and why some of their classmates are happy when Daddy’s team loses. The criticism will be unreasonable and personal. Scheyer’s grin is so naturally wide that it seems destined to become a meme every time Duke loses.

“Those are the things I worry about most,” Laury says. “The notoriety … our little family, it will affect all of us.”

Scheyer says, “We want [the kids] to be a part of it without being consumed by it. I want Marcelle to bring the kids to practice and see me and all those things—but not where we lose a game and that impacts how they are in class the next day.”

Asked whether she worries about Jon taking losses too hard, Marcelle says, “Yeah. I do. But that’s part of the highs and lows that come with it. It goes back to having his outlets.”

Scheyer has vowed to set aside a half hour each day for himself, “just to be creative,” he says. “I think it’s really important that I’m in touch with myself. Then I’m able to get my staff to understand what the plan is going forward.” Duke students should not be surprised to see their coach going for a walk on campus, listening to music or a podcast, even in the middle of a season. This year he even started a journal. “This is a unique time in my life,” he says. “I want to be able to look back on it and see what I was thinking at certain moments.”

Lance King/Getty Images

He tries to put his phone away when he’s with his family, so that even if time is limited, it is meaningful. When he’s in Durham, he makes it a point to tuck his kids into bed every night; his sister Jenifer noticed that he even did it at the team hotel in San Francisco during this year’s NCAA tournament.

Scheyer used to organize pickup games for Duke’s staff, but that dynamic will change now. Who wants to call traveling on the boss? And, anyway, why is the boss playing pickup? After taking two charges last year—once a Blue Devil, always a Blue Devil—Scheyer says he asked himself: What am I doing taking two charges? “I have a bruise on my elbow. I’m pissed at Coach [Amile] Jefferson for a foul he called. … I need to find other ways to keep my mind off of what we’re doing. And playing more basketball doesn’t help.”

He has always been a practical joker. In the locker room after beating Butler for the 2010 national title, Scheyer tweeted, "Hollerrrrr at me!!!,” along with 10 digits—the phone number of an old high school friend. He laments that, as a head coach, he will no longer have time to prank friends with fake pizza orders. But will he still find the space on his calendar for dinner with lifelong friends when he’s recruiting in Chicago? Scheyer has to figure out which parts of himself to retain, and which ones to shed, even as the world looks at him and sees the man he replaced.

Noa and Jett are on the backyard playset, oblivious to the fact that the world has just ended. One night earlier, North Carolina stunned Duke in Krzyzewski’s final home game, and college basketball is buzzing with opinions, most of them wrong.

The Blue Devils, we can see now, a month later, were not really teetering; they made the Final Four. The supposedly mediocre Tar Heels would eventually come within four points of a national title. Duke did play terribly that night, with so many famous alumni watching, and everybody expecting a grand sendoff for Coach K. But while fans assumed his young stars were overcome by pomp, Krzyzewski diagnosed something else: overconfidence. The Blue Devils had clinched the ACC regular-season title. They had crushed UNC in their first meeting. Scheyer says, “We felt like it was just going to happen for us.” The coaches thought that, if anything, they should have made Coach K’s final home game a bigger deal.

Krzyzewski’s genius lies in this gap between perception and reality—in reading minds and hearts, trusting his conclusions and using them to shape his team. Twelve years ago, after Duke came home from a loss at Georgetown in front of President Barack Obama, Krzyzewski asked his captains, Scheyer and Lance Thomas, to stand in front of the team. Duke was 17–4. Scheyer, one of Krzyzewski’s alltime favorite players, had 17 points, five assists and five steals against the Hoyas.

Lou Capozzola/Sports Illustrated

“I thought he was going to put his arm around me and tell me to keep going and Here’s what we’re gonna do,” Scheyer says. Instead: “He lit me up in that meeting. You’re not doing what you’re supposed to be doing as our leader, as our captain.” Scheyer says he was “pissed.” Nolan Smith, a teammate at the time, says that players were on Scheyer’s side. But Krzyzewski surely knew what would happen next: Scheyer became more vocal and authoritative—“making sure that the coaches knew that he was leading, to prove a point,” Smith says. Duke went on to win the national title, over Butler. Krzyzewski had galvanized his team with the counterintuitive tactic of motivating his most motivated player.

Scheyer says that managing people is “the majority of the job, as crazy as that sounds. I mean, of course, strategy and X’s and O’s and player development, all that is incredibly important. But a lot of people have knowledge. They can’t necessarily take that knowledge, share it with you, get you to do it, get you to believe in it. That’s what Coach has done the best.”

That gift is nontransferable. This is probably why many of Krzyzewski’s assistants have struggled as head coaches: They understand that handling people is important, but they haven’t quite figured out how to do it, and so they try to do what they think Coach K would do. Scheyer says that when he interviewed at Duke, “I think that the administration was very curious: Was I just trying to be a Mini Coach K? We’re on the same page, knowing that I need to be different. He doesn’t want me to be him.”

During the playing months, Krzyzewski held 10 a.m. staff meetings in a conference room at Cameron Indoor Stadium, where coaches would discuss everything from ball screens to academics. “Then,” says Smith, who spent the past six seasons on Krzyzewski’s staff, there were “meetings after the meetings.” Every week or two, people would walk upstairs and squeeze into Scheyer’s fifth-floor office, where everybody except Krzyzewski would plan for life without him. Buried in this paragraph is the kind of small decision you might not notice at first—the kind that Coach K would appreciate:

They left the original meeting room. They didn’t have to do that. The gatherings were back-to-back. It would have been much easier to let Krzyzewski leave at the end of his meeting, then stay in the big room and plan for next year. Scheyer laughs and says, “You try to stay out of Coach’s way. He’s down there [in that space], in and out a little bit.” But Scheyer also wanted an atmospheric change for the second meeting, to “keep everybody fresh.” (Out of respect for Krzyzewski, Scheyer agreed to talk to Sports Illustrated in-season under the condition that this story would not run until after the year concluded.)

So much of the job will be about little choices like that, maneuvering people without making them feel manipulated. Should Scheyer’s staff watch video together after every game, as Krzyzewski’s did? Will their emotions infect their analysis? Will they fall into a groupthink trap? Should they watch together the next morning instead? Or should they watch on their own first, so they can draw their own conclusions?

Three years ago, with his mind on becoming a head coach, Scheyer started meeting regularly with a social psychologist in the Duke business school named Aaron Kay. It is common for coaches to talk to sports psychologists about maximizing athletic performance, but, Kay says, “What I teach is not sports psychology. I teach human psychology. [Scheyer] really, sincerely wanted to learn about people and behavior and rationality and what makes regular people tick.”

Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated

Scheyer is already asking questions that many coaches don’t. Is there a way to predict confidence, quantify it, and use that information in recruiting? No matter who he recruits, he will still have to run an organization that, Kay says, will be “full of all types”—young, old, ambitious, burned out, energetic, depressed. Scheyer understands that the key to success is managing all of them.

“In sports, you see a lot of data in terms of performance,” Kay says. “But he’s basically saying: ‘Let’s look to see if there’s a science of running an organization.’”

As a player, Scheyer’s greatest skill was anticipation. Weber, his old high school coach, says he stopped calling out-of-bounds plays because it was better to just give Jon the ball and trust him. Scheyer usually made the right play, but he always expected to make the right play, a quality he traces back to his father always letting him win games when he was little. He had the two qualities he values most, feel and confidence, and he is always looking for them in everybody else.

When Scheyer scouts opponents, he starts by reading about them. “I like to go back to not just who I think the player is, but who the player I’m scouting thinks he is,” he says. “I think that’s really important. On our team, they may be the sixth-best player, but on their team, they’re the best player. And so when you have that mentality, and you’re playing in Cameron, for certain guys, he’s gonna come and try to get 30.”

In men’s college basketball, every X or O starts as an XY. Understanding people’s DNA is a coach’s job. Scheyer grew up as a Jewish kid from a wealthy Chicago suburb, proving himself against kids in the Fellowship of Afro-American Men league. He was the guy who always believed he could get 30 … and then, all of a sudden, he wasn’t.

The summer after he graduated from Duke, in 2010, Scheyer was playing for the Miami Heat’s Summer League team in Las Vegas when Warriors forward Joe Ingles accidentally poked him in the right eye. That happens in basketball. This doesn’t: There was so much blood that “it was about 30 minutes before I even tried to take the towel off,” Scheyer says. When he finally did, he felt like he couldn’t open his eye. But it was already open. He just couldn’t see anything.

“I felt sick to my stomach as soon as I got hit in the eye,” he says. “It was a different kind of pain that I really can’t explain, other than I knew it was something serious.”

Scheyer had a lacerated eyelid, an optic-nerve injury, a retina tear, a scratched cornea, and though he was slow to accept it, a totaled career.

When a doctor told him he would probably never play again, he went home, sank 22 of 25 three-pointers in his driveway and cussed that nobody would tell him that he had to quit basketball. He was Jon Scheyer. State champion. National champion. What had the doctor ever won? “It was always such a part of him,” says Brooke. “He had this way to will things into existence.”

Scheyer played in Israel and Spain, but he told his father that he saw three baskets and shot at the middle one. And when he lost his vision, he lost something else: “I didn’t have that chip on my shoulder that I always had.”

The Duke program is built on institutional belief. We’re going to figure out how to win, because what we do is figure out how to win. Confidence—not just Scheyer’s own confidence, but the idea of it—infuses everything he does. He says he has “absolutely” walked away from recruiting top-ranked players because they lacked confidence. “Just because you’re a top-five talent doesn’t mean it translates to being successful at Duke. The most successful people who have ever come here are the ones who aren’t worried about getting promises or assurances.”

That was Scheyer 15 years ago, and it remains Scheyer today. Everyone now will look to him to lead them through an uncertain and unprecedented time, with athletes able to monetize their name, image and likeness rights, and with a robust annual transfer market. Eight words that would doom him: This is how we have always done it.

Kelley L Cox/USA TODAY Sports

Today’s landscape is “not even recognizable from when I played,” he says. “I think the majority is definitely for the better. You need to be agile. You need to adapt to what’s happening. But we can do our own thing in terms of how we promote our guys. A lot of our planning has gone into that. … We still feel the right guys will want to come to Duke. And NIL, frankly, should help that.”

The Duke job has only grown larger since last summer. North Carolina’s Hubert Davis got a one-year head start on Scheyer, and he almost won a national title. Scheyer has pieced together the No. 1 recruiting class in the country, plus the expectations that accompany it. In December, Smith joked that Scheyer can’t fire him because “he was in my wedding,” but this week Smith left for Louisville, where he will reportedly get a large pay increase and a chance to add to his résumé away from Duke. Now Scheyer has to replace two top assistants: Smith and himself. (Update: On Tuesday it was reported that Elon head coach Mike Schrage, a former Duke staffer under Krzyzewski, would return to Durham as an assistant.)

Scheyer says his right eye is “a team player—it sets screens and gets my left eye open,” but its vision has not improved since that night in Vegas. He never lets recruits sit on his right side at dinner, because then he won’t see them. “The crazy part,” he says, “is my left eye has actually gotten even stronger.” At a recent checkup, his vision on that side had improved, from 20/25 when he got injured to 20/15, helping him see as well as he needs to see—and making up for what has been lost.