Jon Fosse has just been awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature for his “innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable”.

The worthy winner, aged 64, is a major figure in Norwegian literary and cultural circles and the fourth Norwegian to win the most prestigious award in world literature. He’s also the second Nobel Prize for Literature winner in a row to be published (in English translation) by Fitzcarraldo Editions, following French writer Annie Ernaux’s win last year.

Fosse, who the translator Damion Searles calls one of the “elder statesmen of Norwegian letters”, works across multiple genres and mediums and writes using a language called “Nynorsk”, or New Norwegian. (It’s one of two current written forms of Norwegian – used by just 10% of the Norwegian population.) Some, though not the writer himself, have interpreted this as a quietly political gesture.

Anders Olsson, chairman of the Nobel Literature Committee, described Fosse as blending “a rootedness in the nature and language of his Norwegian background” with the artistic techniques of modernism.

Despite having been in the running for the award for a number of years, Fosse, as with several other 21st century European laureates like Elfriede Jelinek and the controversial Peter Handke, is still largely unknown in the English-speaking world.

“I have been among the favourites for ten years, and felt sure that I would never get the prize,” Fosse said in a statement issued by his publisher. “I simply cannot believe it.”

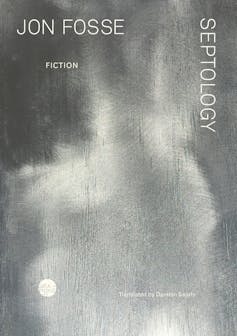

Septology – an experimental tour de force

With the receipt of the Nobel, however, his profile will inevitably rise. This is surely a good thing. What, though, should readers who might be new to Fosse’s body of work expect?

Fosse’s massive literary oeuvre includes roughly 40 plays – the Nobel committee called him “one of the most recognised and widely performed playwrights of our time” – as well as novels, poetry collections, essays, children’s books and translations.

His debut novel, Red, Black (originally published as Raudt, svart), was published in 1983. The first play he wrote that was performed, And Never Shall We Part (Og aldri skal vi skiljast) was staged in 1994.

“It was the first time I had ever tried my hand at this kind of work, and it was the biggest surprise of my life as a writer,” he once said of writing his first play. “I knew, I felt, that this kind of writing was made for me.”

One work in particular stands out, though: his monumental novel sequence, the near 800-page, one-sentence long Septology – written after Fosse converted to Catholicism in 2013. (Formerly an atheist, he had grown up in a strict Lutheran family.)

This experimental tour de force, which was nominated for the International Booker Prize in 2022 for its third volume, focuses on an ageing painter and widower, Asle, living on the southwest coast of Norway. He lives near another painter who shares his name, but is lonely and consumed by alcohol. (Incidentally, Fosse himself famously gave up drinking many years ago, after being treated in hospital for alcohol poisoning.) The doppelgängers grapple with existential questions about death, love, light and shadow, faith and hopelessness.

In the New York Times, Randy Boyagoda rapturously wrote:

Having read the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse’s “Septology”, an extraordinary seven-novel sequence about an old man’s recursive reckoning with the braided realities of God, art, identity, family life and human life itself, I’ve come into awe and reverence myself for idiosyncratic forms of immense metaphysical fortitude.

Read more: Annie Ernaux, French feminist who uses language as 'a knife', wins Nobel Prize for Literature

‘The Beckett of the 21st century’

While a touch gnomic, the Nobel committee’s emphasis on the “unsayable” side of things offers a useful initial means for approaching certain of the more experimental aspects of Fosse’s work, and Septology in particular.

For me, it aligns Fosse’s aesthetic sensibility with that of a much earlier Nobel laureate, the Irish dramatist and novelist Samuel Beckett – who the Nobel committee also compared him to (along with other modernists like Georg Trakl).

Indeed, the the French press has described him as the “Beckett of the 21st century”.

In his 1983 late masterwork, Worstword Ho, Beckett wrote:

Ooze on back not to unsay but say again the vasts apart. Say seen again. No worse again. The vasts of void apart. Of all so far the missaid the worse missaid.

In it, Beckett looks to test the very possibilities of linguistic expression, in keeping with his broader existential project. (Suffice to say: the conclusion he comes to is characteristically downbeat.)

A dauntingly experimental work, in the reckoning of the critical theorist Pascale Cassanova, it “denounces the taken-for-granted realist assumptions on which the whole literary edifice is based”. This is worth keeping in mind when it comes to Fosse.

As the journalist Dani Garavelli notes, in what appears to be a clear nod in the direction of Beckett (who he admires), Fosse “reflects on the inadequacy of language in the struggle for intimacy” in his work.

Fosse has called Beckett “a painter for the theatre rather than an actual author”.

In I is Another, published in English in 2020 (the second instalment of Septology), Fosse writes:

it’s not something to put into words, because you can’t put what a good picture says into words, and as for my pictures the closest he can get to is to say that there’s an approaching distance, something far away that gets closer, in my pictures, it’s as if something imperceptible becomes perceptible and yet still stays imperceptible, it’s still hidden, it is something staying hidden, if you can say it that way […]

Here, as in the pessimistic modernist monologues of Thomas Bernhard (another writer Fosse has been compared to), he touches on questions of artistic and written expression. And, too, on what appear to be the irreducible shortcomings of human communication.

Fosse, who began writing in Nynorsk - which he terms a “minority language” - at the age of 12, seems to have spent much of his life grappling with those questions and limits. Nearly ten years ago, he reflected: “Writing has been a way of surviving.” It remains to be said whether the Nobel will change Fosse’s feelings. Only time will tell.

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.