The relationship between craft and design can be tumultuous. To many people, craft preserves the past, while design forges the future. And yet, in the past decade, we have witnessed an overwhelming resurgence in the practice of craft in the field of design. As the consequences of our globalised, homogenised and rampantly commercial behaviours become ever-more evident, we are re-evaluating the potential of craft, not just as a substitute for our wanton ways, but as a solution for our ignominious ills. The power of mind, hand and material meeting the needs of people in time and place is the original purpose of both craft and design. Surely they can work together in harmony rather than in opposition?

This is the question that Leipzig-based designer Johanna Seelemann has tasked herself with answering in her practice, which is currently focused on the Ore Mountain region, or Erzgebirge in German, of her native homeland. Travelling through this hilly borderland between east Germany and the Czech Republic, visitors will happen upon signs outside every second house pointing to carpentry workshops.

Johanna Seelemann's craft inspired by her homeland

Following the decline of the mining industry in the 17th and 18th centuries, the canny inhabitants turned their attention to their other big resource, trees, with wood-turning being the dominant modus operandi. The Erzgebirge region has since become the epicentre of production for the particular decorative objects that one associates with Mitteleuropean Christmas markets: nutcrackers, fir trees, candle arches and pyramids. ‘We all grew up with them in our homes,’ says Seelemann. ‘They were a core part of our annual rituals in the run-up to Christmas.’ Today, there are around 16,500 wood-turners in the Erzgebirge region.

So far so cosy, you may be thinking. Could there be a more idyllic image of old men in woody workshops carefully making snowy figurines for the most wonderful time of the year? The uncomfortable truth is that, within the next decade, 50 per cent of the workshops are set to close. As the old men hang up their tools in retirement, there are no young people waiting by the wood piles.

In fact, there are few young people living in these villages, let alone young woodworkers keen to continue the family business. Salaries for the artisans are low and it is not an attractive proposition for younger generations. Combined with the broader secularisation of society, dwindling enthusiasm is rendering this particular craft tradition, and the communities it supports, not just precarious, but critically endangered.

Enter Seelemann and her particular mode of design as an anthropological and social tool for improvement. She describes her ‘fascination for unravelling the objects that we might take for granted’. For two and a half years, together with photographer and fellow Erzgebirger Robert Damisch, the pair have been documenting and gently infiltrating the community to assess how best they might reawaken what they believe to be a sleeping giant. Seelemann talks about their mission plainly: ‘We are trying to connect craftspeople to younger people and different audiences. We are interested in developing platforms beyond the Christmas markets and beyond the region. The knowledge and skill of this region is immense and has enormous potential.’

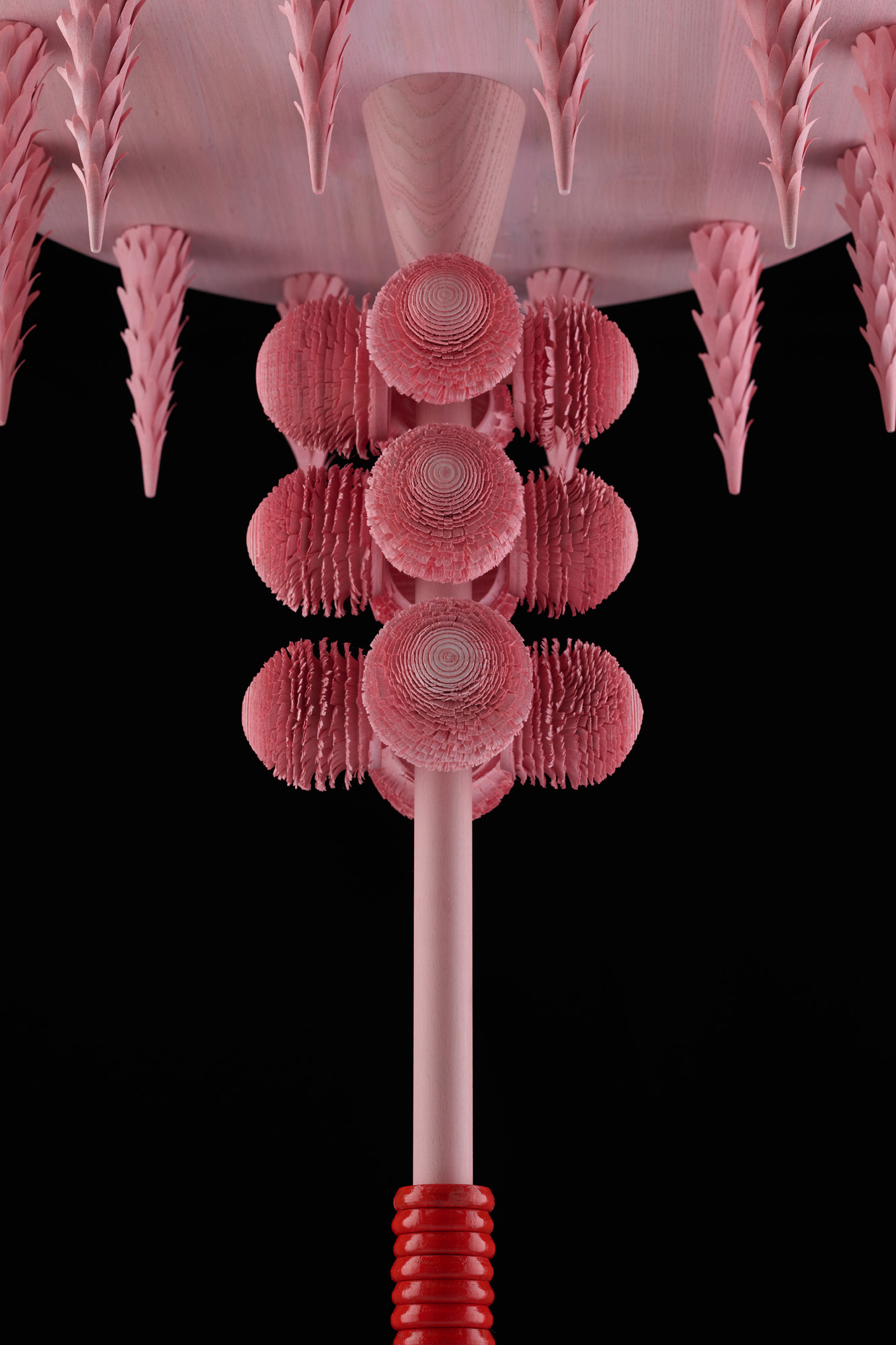

The first physical output of Seelemann is the arresting ‘Satellite’, a candy-coloured LED-lit chandelier. Sponsored by the Dregeno Seiffen woodworkers’ association in Erzgebirge, it was commissioned by the curator Alice Stori Liechtenstein and exhibited at her always-fascinating Schloss Hollenegg for Design earlier this year. A rambunctious creation, combining the fantastical imagination of Roald Dahl with the exuberant expression of the Memphis Group, it is entirely made from component parts from the Erzgebirge workshops that might otherwise have found their place as polite candle pyramids or noses for nutcrackers on the windowsill of a German suburban semi. By contrast, ‘Satellite’ belongs centre stage in a palace.

This tactic of design is far cleverer than one might first assume. It is not about making humble craft appropriate for a gallery; in the first instance, it is a communication tool for capturing people’s attention. ‘Wow’ and ‘gosh’ is very much the intended response. ‘Alice Stori pushed us for something wild and experimental,’ says Seelemann. ‘The real issue in the region, particularly where young people are concerned, is the attitude towards it,’ says Damisch. ‘Our goal is to attract attention and inspire people to think differently, to open their minds to the possibility of what might happen with what exists. Opening up a discussion with a propositional object was our primary objective,’ he adds.

In her Leipzig studio, Seelemann is holding up a series of intricately turned and carved wooden trees, each with a different texture and distinct personality according to its tooling technique. Away from the Erzgebirge workshops, in Seelemann’s hands, the trees are liberated to become something less literal. She is working on tables and lights, incorporating the whimsical properties of handmade elements into intriguing objects for a range of domestic purposes. Importantly, they bear the hallmark and character of the Erzgebirge tradition – Seelemann is not trying to disguise or dilute the hallmark skills that made the region famous, rather she is recontextualising them to augment their potential.

‘Many of the craftspeople struggle with the idea of change and find what we are doing shocking,’ admits Seelemann. ‘We understand, of course; we are consciously trying to bring a different perspective to something familiar, something that people feel deeply attached to. Some people will never accept that trees can be upended to become table legs,’ she laughs. ‘And yet, our design methodology is to be radical to create space for young people to imagine a life for themselves in Erzgebirge. We are not just trying to find people to carry on traditions, we hope to inspire people to evolve heritage skills into future traditions. We have to inspire people to understand that they can bring their own vision to the workbench more than just taking over the workshop from their father.’

Erzgebirge’s prognosis is echoed in a thousand communities and cultures where successful artisanal traditions have backed themselves into a corner to become crafts in stasis more than evolution. Just as design has increasingly looked to craft of late to help re-establish its human roots and soul, so the methodology of design can repay the favour by helping craft to resurrect its relevance and potential in contemporary life. What’s at stake is more than just nutcrackers, it is the knowledge intrinsic to the social infrastructure of a rural economy and its cultural identity.

A version of this article appears in the January 2025 issue of Wallpaper* , available in print on international newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today.