You might think a diagnosis like pigmentary glaucoma would be the kiss of death for a guitar player's career. But don't tell Steve Hunter that – he's more creative than ever.

Of course, creating music without sight is no easy task. As such, his process is slow-moving. But Hunter is hard at work – and has nearly completed – his first solo record since 2017's Before the Light Go Out.

"I guess it takes me a while to work on these things," Hunter tells Guitar World. "But I have a good excuse because of my eyes. The issues with my vision tend to slow me down when I'm working on the computer, so the whole process slows to a crawl compared to someone with normal eyesight."

Despite the obstacles, the often blues-leaning rocker has found more than a few ways to turn what would end many players' careers into a point of pride through reinvention.

I've had to do things like try to find landmarks that I put in place with tape on the back of a guitar and things like that. It helps me feel where I am on the guitar if I get lost or disoriented. It’s tough, but it's made me a better player

"I think being legally blind has almost made me better in some ways," Hunter continues. "But having played most of my life with good enough sight to see what I was doing and gradually starting to lose my sight has been difficult. Now I try not to look at the guitar because that helps me acclimate to where I am."

Indeed, in recent years Hunter's public appearances have been few and far between due to the issues with his sight. As any player who has spent any amount of time on the road would probably agree, the idea of trying to rebuild what you've always known on the fly – in front of an audience – can't be easy.

To that end, Hunter says, "I was constantly nervous that I was going to be on the wrong fret and not know until it was too late. That took a lot of the fun out of playing live, so I don't do that much anymore. But in the studio, if I mess up, at least I can re-record it."

He continues, "I've had to do things like try to find landmarks that I put in place with tape on the back of a guitar and things like that. It helps me feel where I am on the guitar if I get lost or disoriented. It’s tough, but it's made me a better player."

But it's not all bad, nor is Hunter stuck in the stone age. Looking at the guitar with a fresh perspective has led him to explore options that might make tone-chasing a bit easier.

In response to the combination of amps he's deploying, Hunter muses, "That's a bizarre question because the technology has gotten to the point now where there are lots of options, which I've been waiting most of my career for."

Digging deeper, Hunter says, "For the longest time I’d roll a Marshall half-stack in and crank it up. I can't really do that in a small apartment, you know? But there are all these new plugins that, for a long time, weren't very good but have come a long way in that they sound more real."

But while that might sound as if Hunter has given his trusty tube amps the boot, it's not the case.

"I still use an amp," he quips. "I have a Vox AC15, and I have three good mics. That, along with these crazy plugins, has given me options and allowed me to have a lot of fun when trying to dial in different tones."

Hunter continues, "People will say after you do a solo, when you listen back, you're going to hate it. And back in the old days, you were stuck with it because of the limited options."

Now I can take a sound and manipulate it with presets. I know a lot of the old-school guys will be mad at me for that, but I can't roll a Marshall in here

He continues, "But now, I can take a sound and manipulate it with presets. I know a lot of the old-school guys will be mad at me for that, but I can't roll a Marshall in here. I've got to make the best of what I have at my disposal."

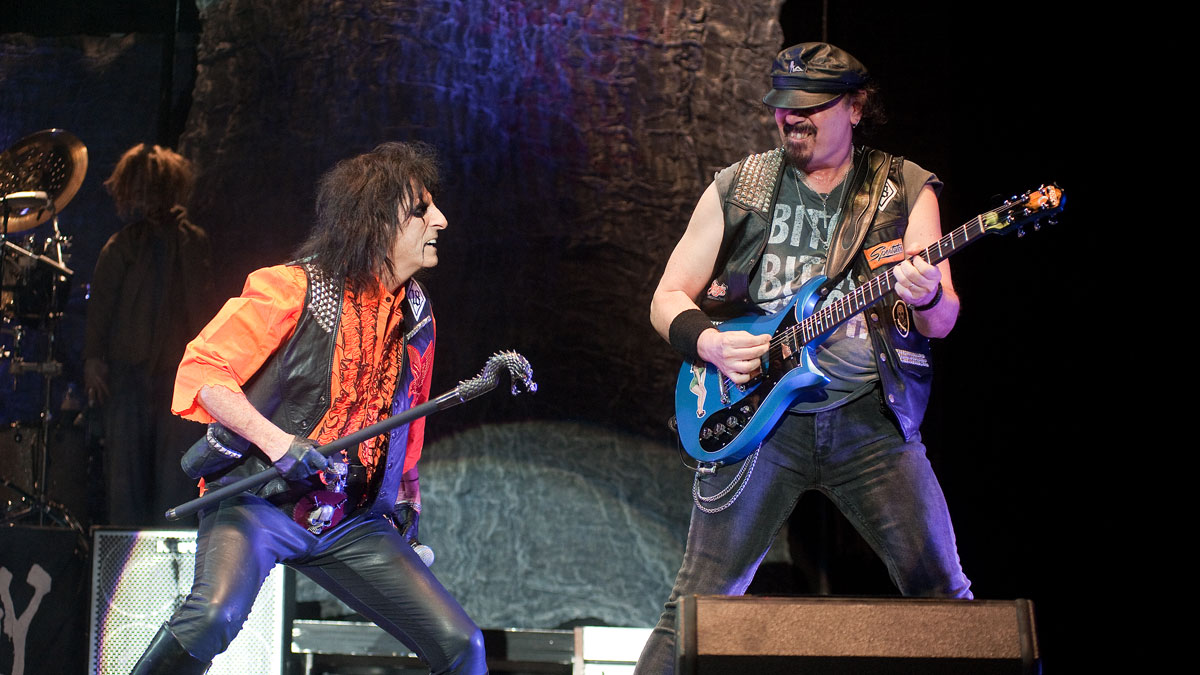

Steve Hunter dialed in with Guitar World to talk gear, session work with Alice Cooper, Aerosmith and Peter Gabriel, and his longtime friendship with Jason Becker.

You started your career with Mitch Ryder. How would you compare your approach now to your early days?

"I don't think it's a whole lot different. When I was young, I was pretty naïve as a player and writer. Back then, I was just learning rhythm guitar, as well as lead and there was just a ton of stuff coming at me. There's always been a continual learning process."

Considering your bluesy nature, I always felt your work with Lou Reed was an interesting juxtaposition.

"Lou's stuff is a bit more bluesy than it's given credit for; I still remember writing the intro to Sweet Jane while sitting on a couch in my living room. It was just this thing that I put together with an old acoustic guitar, and later, I was out on tour with the Chambers Brothers – I'd play that same intro with them. It had no name, but after I got together with Lou, he liked it, and we turned it into the intro for what became Sweet Jane."

How did your approach change after you began working with Alice Cooper?

"When Bob [Ezrin] would call me into a session, he knew what he wanted. I remember sitting in the control room with Bob late at night, and Bob played me this song called Sick Things, and I was like, 'Oh my God… what am I going to play?' So, that was the most challenging part: adding things to these compositions that were all so different. That made me nervous and, honestly, a little worried. So, my approach was trying to sound professional and then, add something cool."

Was Alice's music mostly out of your comfort zone?

I remember one night I put blood capsules in my mouth, and when Dick swung, I bit down, and he thought he hit me

"Well, there were times when I'd say to Bob, 'What do you want me to play?' And sometimes he would say, 'Play some Eric Clapton blues,' or 'Something like B.B. King.' Some of it was a little shocking, but my style worked well. And when it came time to do a solo, I tried to stay within the blues as much as possible. But when I say 'blues,' everybody thinks traditional blues; that's not what I'm saying. For me, the blues is more of a feeling than anything else. It's the phrasing and melodies that count most."

How did your infamous guitar face-off with Dick Wagner come to be?

"The way it happened was there talk that we needed something extra in the middle of the show when Alice had a costume change. So, I thought, 'Hey, instead of doing a traditional guitar solo, why don't we give them a real duel?' And the face-off happened where we'd trade licks back and forth, and at times, it became ‘violent’ where we'd take fake swings at each other. I remember one night I put blood capsules in my mouth, and when Dick swung, I bit down, and he thought he hit me [laughs]."

How did you end up in the studio with Aerosmith to record the first solo in Train Kept a Rollin'?

"It happened out of the blue one night. I think there was a sort of political thing going on. All these labels were signing bands with people they thought could play, and they’d get upset that albums were coming out with all these studio musicians on them. They were paying all this extra money for additional people, and second, they signed these bands in good faith that they could play."

It sounds like your participation would have had to be kept a secret.

"They definitely didn't want people to know. But the thing is, when you cut an album, it's set in stone. It's not like a live gig where you can have a bad night and make up for it with a good one. It was important that these albums be as good as possible, and that's basically why I was called into the studio to play on Train Kept a Rollin'. The way it was explained to me was, ‘Joe [Perry] had hit a block,’ and they needed to get the take done and start mixing the next day."

Was Joe aware of it at the time?

"Probably not. But it was no big deal; I had hit blocks like that in the studio hundreds of times. And that's what happened with Joe on Train Kept a Rollin'. So, they saw me sitting in the studio lobby smoking a cigarette, and Jack Douglas poked his head out and said, 'Hey, do you feel like sitting in for a session?' And I said, 'Yeah, sure. What do you need?'"

Did they ask you to play like Joe?

"They told me what they were looking for; I gave the solo a couple of passes, they were happy, and that was it. And then I went back and sat down in the lobby again. Now that I think of it, they did say, 'Look, it's best if we don't mention to anyone that you played on this. Don't tell anyone; no-one can know.' I don't think it was ever mentioned until Joe left the band years later. It was kind of a bummer that no-one could know, but by that point, I was used to the double-edged sword of session work."

Another notable session includes your work on Peter Gabriel's Solsbury Hill. Some reports say you played on the track; others say it was Robert Fripp.

"Oh, it was me. Robert has been honest about that, too. What happened was we were working on Peter's album, and Solsbury Hill was the last song we were to record. But Robert had to leave before we started because he had a session in London, and it was left to me. I wasn't worried, but looking back, it could have been a bit scary because the time signature was a little weird, and I was still kind of a naïve player."

Naïve, perhaps, but your Travis-style picking is bang on.

"That came about because Bob Ezrin was in the studio, and he was the one who suggested I go with the Travis-style stuff. I remember thinking, 'OK, Steve, you're either gonna fall flat on your face or pull this thing off.' So, I put a capo on the second fret and started working out the chords, and to my surprise, the song was so well written that it never felt uncomfortable. It only took me a couple of takes to where I said, 'OK, I'm fine. I'm not gonna have any trouble.'"

How did you first connect with Jason Becker?

"Jason came over for a few guitar lessons because David Lee Roth wanted him to ‘add a little more blues in’. So, he sent Jason to me for some lessons, and when I listened to his Cacophony stuff, I was like, 'Oh my God, what can I possibly show this guy?' I didn't think he would be interested in what I had to say, but he came over anyway, and within five minutes, we hit it off."

What was the common ground between you two?

"I saw that he had a great love for the guitar, respect for other players, and a great respect for music. So, I asked him, 'Who is your favorite guitar player today? Who have you listened to today?' And he said, 'Stevie Ray Vaughan,' which knocked me off guard. And I said, 'OK, alright, that's good. How would you like to hear where Stevie Ray got his stuff?' And I put on an old Albert King album called Years Gone By, and Jason was floored by it."

What was your experience working alongside Jason on David Lee Roth's A Little Ain't Enough?

"I don't know if I taught Jason much, but I left him with a deeper respect for the blues. I ended up giving him that Albert King album I mentioned because he could hear how Stevie Ray Vaughan had absorbed a lot of that stuff. And from that moment on, he and I became best friends. We were really different, but I had such a lovely time working with him up in Vancouver on David Lee Roth's album."

I take it you two are still close.

"Oh, yeah. We bonded while working on that album. We'd work all day, then go out at night, hang out, and walk all over Vancouver. We had a great time, and Jason is still one of my best friends. And that didn't change after his diagnosis with ALS. I have great respect for his ability. Jason Becker is a genius. He was a special player and an incredible person."

Have you settled on a release date and title for your impending solo record?

"The release date is hard to predict because of my slow pace, but I'm hoping we have it out by early fall '23. As for the title, I’m leaning toward The Deacon Speaks. There’s this photo of me sitting and waiting to be picked up outside our apartment that my wife took, which inspired me, too. I thought that would make a great album cover, so we'll probably go with The Deacon Speaks."