By his own admission there are least seven films woven into Naqqash Khalid’s debut feature In Camera, a singular picture that on its surface alone taps into the unrelenting nature of acting and the industry’s phoney relationship with identity politics. ‘Filmmaking is like an iceberg, a lot of stuff you put under the surface,’ reflects the writer-director. ‘Then when an audience pulls something out, it's really validating.’ Pitched in its earliest form as a concept album via a word document dressed up as a Tumblr, Khalid ultimately produced a contemporary riff on the fairytale, albeit one informed by the British New Wave that loops in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and hopes to evoke the beat switch in Frank Ocean’s ‘Nights’.

"I feel like my brain is a blender. Everything I've ever put into it inspires me, but I really wanted to make a fairytale"

Director, Naqqash Khalid

‘I feel like my brain is a blender. Everything I've ever put into it inspires me, but I really wanted to make a fairytale. I’m interested in representing life as it feels, not necessarily as it is, and there’s a fluidity that fairytales offer,’ he explains. ‘I'm playing with tonalities and genres a lot with this film, but there is something really traditional about a protagonist in a fairytale going from innocence to experience. So I'd say this is a post-colonial fairytale, this character is coming into whiteness almost, or a certain type of masculinity.’ Indeed, when we meet Nabhaan Rizwan’s Aden, a jobbing actor and ready sponge for a multitude of projections, he’s inherently a vehicle for the ‘anxious young man’ archetype, today’s stand in for the ‘angry young man’ of early 1960s cinema suggests Khalid.

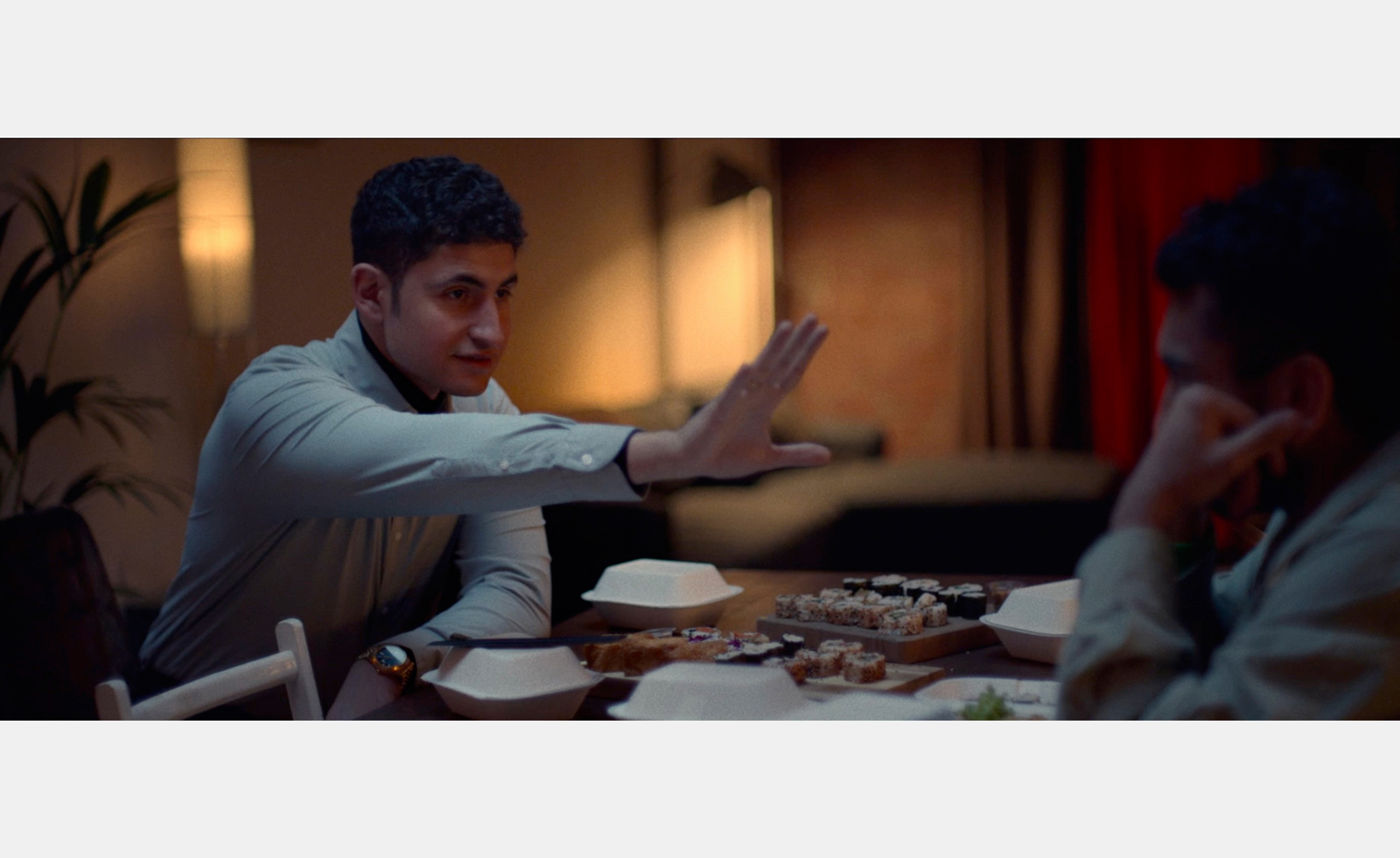

‘I love actors and the medium of performance; how human the art form is,’ he continues. ‘Performance is so interior, and I'm really inspired by modernist literature that plays with streams of consciousness and articulating interiority. There's something so interesting about everything a face and body says, but doesn't tell you necessarily in words.’ This concept is perhaps most distinct in Aden’s new housemate Conrad (Amir El-Masry), a creative director type working in fashion, whose confident bravado is largely experienced through hand gestures. With Bo meanwhile (Rory Fleck Byrne), the overworked junior doctor with whom Aden had previously, apparently, lived alone, Khalid employs some of the film’s more overt surrealism: buildings violently haemorrhage on his watch, a vending machine appears in the middle of the road.

Moreover, throughout In Camera dialogue, props and scenarios are duplicated, becoming echoes and visual curiosities; in a therapist’s office two clocks are stacked one above the other, as elsewhere Aden redelivers lines imposed in prior setting, or mirrors Bo’s use of the stethoscope, the two men variously unnerved by strange noise. ‘Repeating and doubling is everywhere,’ asserts Khalid. ‘Geometric abstraction was huge for this film, tessellations, repeating patterns, loops. I knew early that this story was going to loop and repeat, and so I was looking at artists like Rasheed Araeen and Anwar Jalal Shemza to really inform the structure of the film.’

Anchoring the wider picture is a stream of study that underscores the filmmaker’s bold intentions and academic perspective (Khalid dropped out of his PhD to make the film). ‘I was reading lots of abolitionist literature – Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, bell hooks, Angela Davis – who all talk about this idea of reimagining society,’ he says. ‘That was really inspiring, like how do you inherit systems that are fundamentally broken? Naomi Klein's On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal was really big for this too, how she talks about the role of the artist and this radical thinking that recognises the system we're currently living in is killing us, be it climate, patriarchy or white supremacy.’

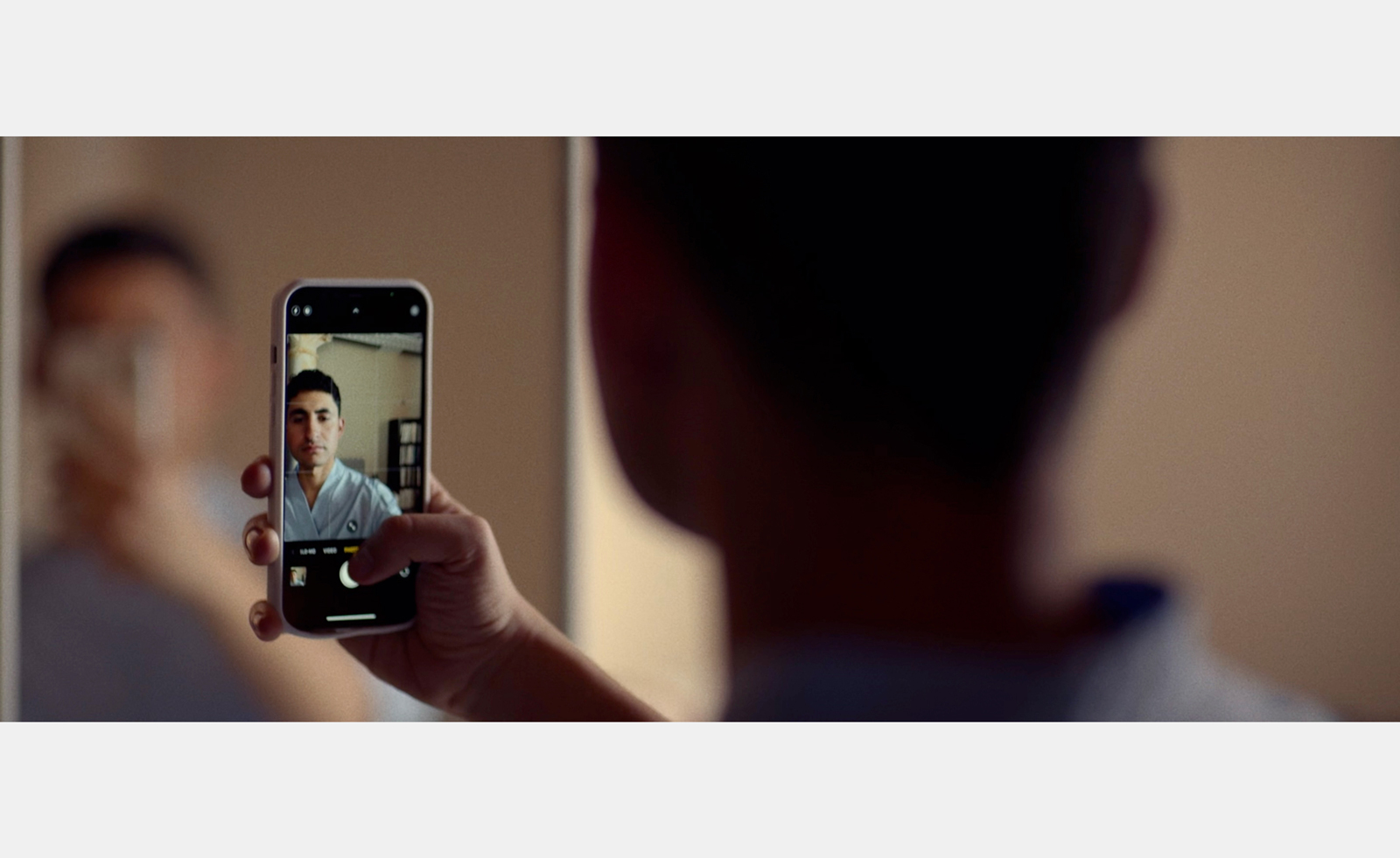

Describing himself as a creative outsider, Khalid recognised early on the potential – and necessity – for challenging typical filmmaking practices. ‘Let’s be real, cinema was developed by the military. The techniques and equipment we use has been used against people who look like me – photographers, originally, were sent to the Global South to take pictures to almost justify subjugation,’ he notes. ‘Even today, on a technological and psychological level, it’s a medium that harms people. So I'm having to invent and reimagine what I want to do within this medium, interrogating it to make it work for me.’

"Even today, on a technological and psychological level, [cinema is] a medium that harms people. So I'm having to invent and reimagine what I want to do within this medium, interrogating it to make it work for me."

Director, Naqqash Khalid

‘All of that sounds quite didactic and intellectual: how do you put it into a film that's funny and entertaining?’ he continues. One response was to play with etymology, in particular as it relates to ‘shooting’. In an already fraught scene on a photographer’s set then, Khalid and sound designer Paul Davies replaced the noise of the camera shutter with gunshots. ‘I know a normal audience member isn’t going to pick up on that, but to me, every layer transfers, it registers in some way,’ says the director. ‘I'm kind of obsessed with discomfort, so there's lots of anxiety and violence all over the sound design, that is not necessarily present visually. It goes back to my core intention: as soon as you're invested in interiority and how something feels to somebody, that is liberating and freeing because there are no limits.’

In Camera is in cinemas now