Joan Didion leans against her Corvette Stingray, a cigarette perched between her fingers. Her unsparing, unsmiling gaze seems to sear through the lens of photographer Julian Wasser’s camera, and one arm – the one that isn’t attached to the cigarette – is folded across her waist like a shield. She looks standoffish, effortless, cool. This black and white image, captured for Time magazine after the publication of Didion’s 1968 journalism collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, quickly became part of the writer’s iconography. You can buy totes, prints and T-shirts emblazoned with it – particularly useful if you want to not-so-subtly proclaim your highbrow reading tastes and love of pared-back prose.

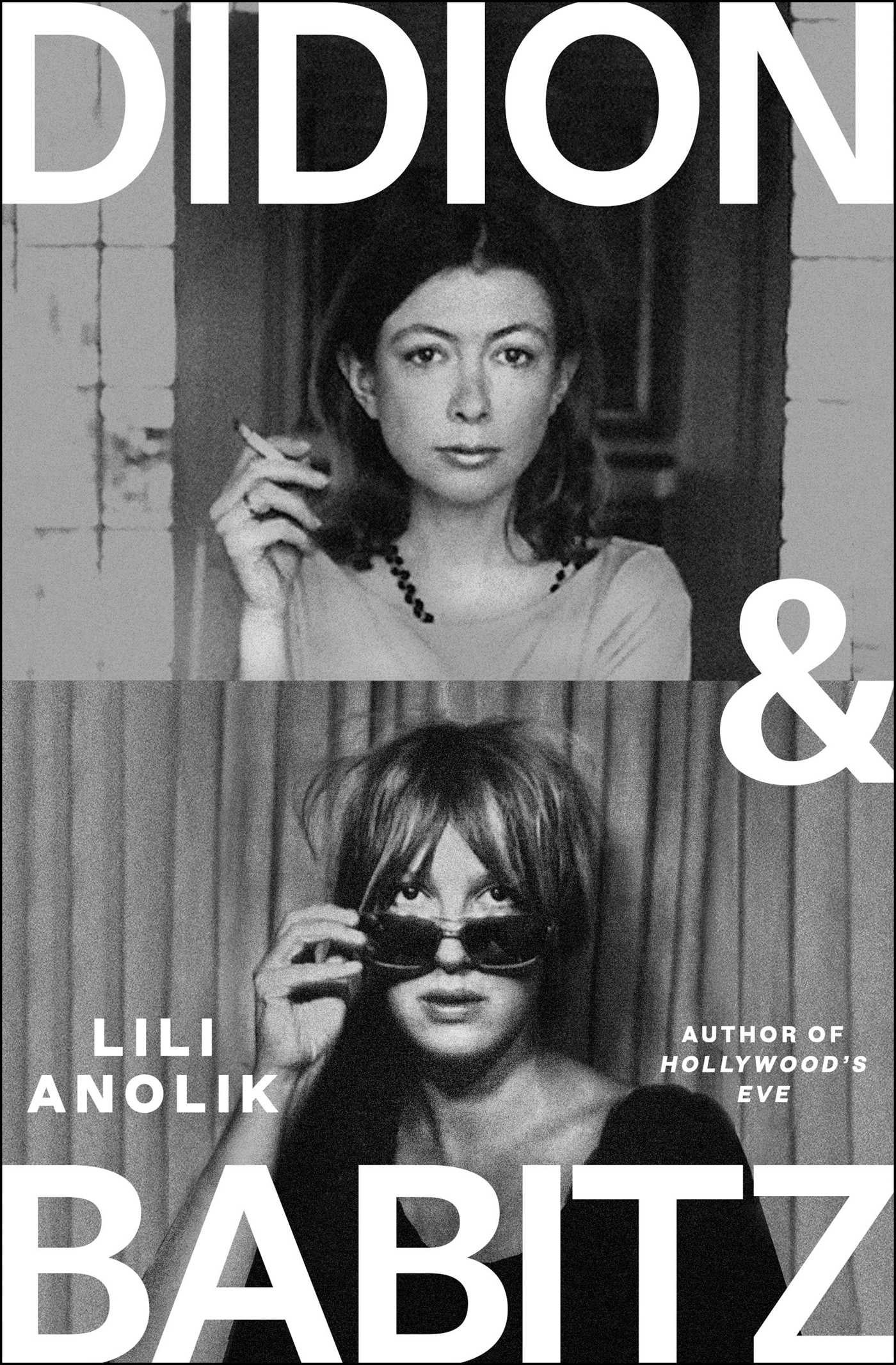

But five years before Wasser captured this defining image of Didion, he took another, very different picture, one that’s just as striking. In it, the 20-year-old Eve Babitz sits at a chessboard opposite the artist Marcel Duchamp, her face obliterated by a curtain of dark hair. It’s the only thing about her that’s covered up: Babitz is completely naked, while Duchamp is fully dressed. These photos seem like polar opposites – and so, in many ways, were Wasser’s subjects, who chronicled the Los Angeles of the Sixties and Seventies in very different ways. The complicated dynamic between these sometime friends is the subject of Lili Anolik’s dazzling new book Didion & Babitz.

What’s also fascinating is that, whether they did so knowingly or not, both writers – who died within days of one another in December 2021 – set out the template for what it means to be a so-called literary “it girl”. As such, their image and their words are now often co-opted as signifiers of literary cool. They’ve become poster girls for literature as lifestyle. Their quotes and black and white portraits appear on well-curated Instagram grids, and their beautiful faces stare out from canvas bags. But how did they get there, becoming “cultural heroines as much as literary [ones]”, as Anolik describes them to me?

Didion & Babitz traces the two women’s contrasting, sometimes overlapping career trajectories. The former’s more straightforward ascent is much better known. Didion won a Vogue essay contest as a young woman, then got a job composing photo captions for the magazine. While she worked there, she wrote her first novel, Run, River. But it was Slouching Towards Bethlehem that made her a star. Her writing was clean and precise; her scrutiny of LA’s counterculture unflinching.

Didion’s reputation soared further with the release of The White Album, another essay collection, in 1979 – and unlike so many authors, her work never went out of fashion as the decades changed. Then in her seventies, she won the Pulitzer Prize for The Year of Magical Thinking, her moving account of the aftermath of her husband John Gregory Dunne’s sudden death. (Dunne was also her valued collaborator, editing much of her work and co-writing screenplays with her). The cult of Didion only intensified as she got older. She modelled for the chic, minimalist fashion brand Céline in 2015; the same year, another high-end label released a $1,200 leather jacket with a drawing of her face emblazoned on the back. In 2017, she was the subject of a Netflix documentary, The Center Will Not Hold, directed by her nephew Griffin Dunne.

Babitz’s story is far more chaotic and convoluted. She grew up in Hollywood in an arty milieu (the composer Igor Stravinsky was her godfather). Later, as Anolik sums it up to me, she started “designing album covers” for bands such as The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield, and “was the groupie supreme, and had a sex résumé that is second to none”. She was linked to just about every edgy LA celeb of the era – Jim Morrison, Harrison Ford, Annie Leibovitz, Steve Martin. She inevitably drifted into the same circles as Didion, who would later put in a good word for her with an editor at Rolling Stone, providing Babitz’s writing career with an initial shock of momentum. Her first book, 1974’s Eve’s Hollywood, is a heady evocation of life at the epicentre of the California scene, occupying a kind of dreamy no man’s land between fact and fiction.

If Didion’s writing is stark, Babitz’s is sprawling; if Didion put Los Angeles under a critical microscope, Babitz viewed it through a rose-tinted, sun-drenched, slightly (OK, very) druggy haze. Indeed, in the name drop-heavy dedication for Eve’s Hollywood, Babitz thanked the Didion-Dunnes for “having to be who I’m not”: “[Didion] and Eve were kind of opposites, who were also doubles,” Anolik says. Slow Days, Fast Company, the essay collection that Anolik sees both as Babitz’s masterpiece and an analogue to The White Album, followed in 1977. So did novels such as Sex & Rage and L.A. Woman and the story collection Black Swans. (Is it any wonder that Babitz’s books now often appear ever so casually in stylish Instagram posts when the titles are this good?)

But her output and quality could be erratic, often influenced by her drug use, in contrast to Didion’s steady craftswomanship. In 1997, she suffered severe burns after accidentally setting herself on fire and retreated from public life. By the time that Anolik chanced upon Babitz’s name in another book and ordered a second-hand copy of Slow Days, her works were long out of print. “I was just sure that she was the secret genius of Los Angeles,” Anolik says. She managed to track Babitz down in LA; their lengthy conversations inspired a 2014 Vanity Fair piece and a 2019 biography that helped reignite the reading public’s interest in both her glamorous life and her literary works, which were eventually reissued. A new generation of readers has since fallen for her breezy but acute insider’s perspective on a showbiz scene that seems so much rawer and more exciting than today’s sanitised version.

Anolik had drawn a line under Babitz’s story – but then, after her death, Babitz’s sister Mirandi discovered a box filled with unsent letters and journals and alerted the author. When she eventually sifted through the contents, “my stomach dropped to the floor”, Anolik says. The first letter she pulled out was addressed to “Dear Joan”. In it, Babitz seemed to upbraid her friend and rival for refusing to read Virginia Woolf – “I feel as though you think she’s a ‘woman’s novelist’ and that only foggy brains could like her” – and simultaneously adopting a shield of femininity, even frailty, when it suited her. “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” Babitz blazed. “Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening?” (Didion’s writing is littered with references to physical smallness, and she was always thin, famously subsisting on almonds and chilled Diet Coke – in a society still obsessed with thinness, it’s hard to divorce her size from her muse status.)

Reading the letter, Anolik felt, was like “eavesdropping on a fight, a lovers’ quarrel. It [was] intensely personal, and the emotions are so volatile and passionate.” It’s as if Babitz has managed to see through Didion: the brand, although there’s an irony to her criticising Didion for not sufficiently supporting women writers, given the way she’d initially championed Babitz’s career. From other letters, Anolik also learned that Didion had briefly acted as editor on Eve’s Hollywood, something Babitz had never mentioned in their own conversations. “It wasn’t an overlooking, it was an obfuscation,” she says. “We had talked about the genesis of Eve’s Hollywood so many times, and I had known that Joan got her into Rolling Stone, but this was at a totally different level.” She was fascinated by the fact that “both women wrote the other out of history” – neither appears in the other’s writing much, even when they’re recounting social scenes that both were part of.

Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening?

Anolik explores both writers’ personas – how they were made, and how they might have repelled and attracted one another. Part of what makes Didion & Babitz such an intriguing read is the way that the author uses Babitz – her letters, her story, her words – to illuminate and skewer the way that Didion carefully crafted her writerly image. The woman effortlessly perching by the Corvette was anything but.

“Didion writes in a confessional style, it’s a lot of first-person journalism, but she’s really an opaque character,” Anolik says. “She’s quite guarded, quite hidden, and any information you find out about her, it’s information she wants you to know about her. So she’s hard to get inside. And Eve, in a totally different way, was equally hard to get inside. She seems open, and she’d answer your questions … [but] she would be violating her sense of style, of who she was, if she complained.” Her letters and private writings showed another side to the Californian sunniness: her voice was “sharper, darker, more devastated, less casual”, Anolik puts it in her book.

Over the years, veneration of Didion has solidified and sentimentalised (a process helped along by the tote bags and the Instagrammed quotes). “People take her really personally,” Anolik says, referring to the legions of fans who have adopted the writer as a sort of very stylish secular saint. Using Babitz as a prism allows Anolik to pierce that reputation and show a different side to her. Sometimes Didion emerges as cold and strategic. Anolik’s book, she adds, is “kind of a ‘how to guide’, how to become Joan, [exploring] what it took to become ‘Joan Didion’ and the price she paid, and was willing to pay … You don’t reach that level without being a very hard driving, very tough-minded person. She did have her warm moments, but to me, the work and being a great writer is what meant the most to her.”

For Babitz, though, “thinking in terms of career trajectory was antithetical to what she [was]. And that’s an artist, right?” Anolik says. “She couldn’t bear to think in this other way. Joan certainly was an artist, but Joan was so shrewd about thinking in that way.” So if Didion’s “it girl” style image was deliberate, Babitz’s was haphazard, accidental, belated (paradoxically, of course, that only adds to its cool). In her initial Vanity Fair piece, Anolik says, she “was able to give [Eve] a persona which I don’t think she bothered with at the time she was writing. She was living this wild, glamorous, dangerous, lustrous life that would be hugely appealing to people, but she somehow wasn’t publicising it”.

[Eve] was living this wild, glamorous, dangerous, lustrous life that would be hugely appealing to people, but she somehow wasn’t publicising it

Anolik is ambivalent about the “literary it girl” label. On “some aesthetic level”, she says, she objects: “it sounds weirdly sexist, pejorative to me.” And yet, years of “looking at literary careers … from some distance” has shown her that “the writers that seem to have the best chances of survival [have to] write great, but their persona has to be really thrilling to people in some way”. She points to how F Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway (perhaps America’s earliest “literary it boys”, not that they’d ever be referred to as such) “seemed like their own characters, embodiments of the age and excesses in which they were living… The work and the life [of the writer] just blends… and that’s what people respond to.” We use these writers and their work as avatars of the lives we want to have: the impulse plays out again and again, in the ways we’ve celebrated so-called “it girls” as different as Nora Ephron, Zadie Smith and Sally Rooney.

Literary persona, then, can be “profound and important”. When Didion posed in front of the Corvette, she presaged her character Maria in her novel Play It As It Lays, who drove the same car, had the same style, same attitude. And even if Babitz was a less shrewd image-maker than her frenemy, she certainly wrote versions of herself into her books as the perennial protagonist; Jacaranda in Sex & Rage is a barely disguised self-portrait, as is Sophie in L.A. Woman. “There’s this confluence of character, persona, writer,” Anolik says. “It all blends in this way that captures people’s imaginations.” It’s this heady mix that makes those two antithetical, enigmatic photos of Didion and Babitz so bewitching – frankly, we want to be them as much as we want to read them.

‘Didion & Babitz’ by Lili Anolik (Atlantic Books, £20) is out now