Of all the albums to emerge from the British blues boom of the 60s, few had the impact of John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers ‘Beano’ album, featuring 21-year-old guitar god Eric Clapton. In 2011, the late Mayall and others looked back at the making of an album that would inspire countless generations of blues fans and musicians alike.

Summer 1965. An Immediate records session at Decca studios, 165 Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead, North London. Men wearing white lab coats over shirts and ties, their hair neatly trimmed, stand mouths agape.

In the past, perhaps, they had shared a chuckle after telling a bassoon player to quieten down or tutted, recalling that time when the dials quivered in response to an over-enthusiastic triangle player. Today the volume is such that cakes are rolling off their plates, tea cups rattling in their saucers. Suddenly the engineer in charge comes to his senses and turns off the tape.

“This guitarist is unrecordable!” he tells the producer, a young long hair by the name of Jimmy Page.

Page remains calm. A guitarist himself, he already has an impressive track record of session work behind him and, as a young man in touch with the nation’s youth, has been entrusted to deliver a new kind of record. The guitarist on the other side of the control room glass is a 20-year-old guy called Eric Clapton. He has plugged an imported, US-made Gibson Les Paul into an amp made by a new British company called Marshall. The sound is like nothing the engineers have had to deal with. They can’t believe that Clapton is creating this noise on purpose. Page, on the other hand, understands completely.

“Switch it back on,” he tells the engineer. “I’ll take full responsibility…”

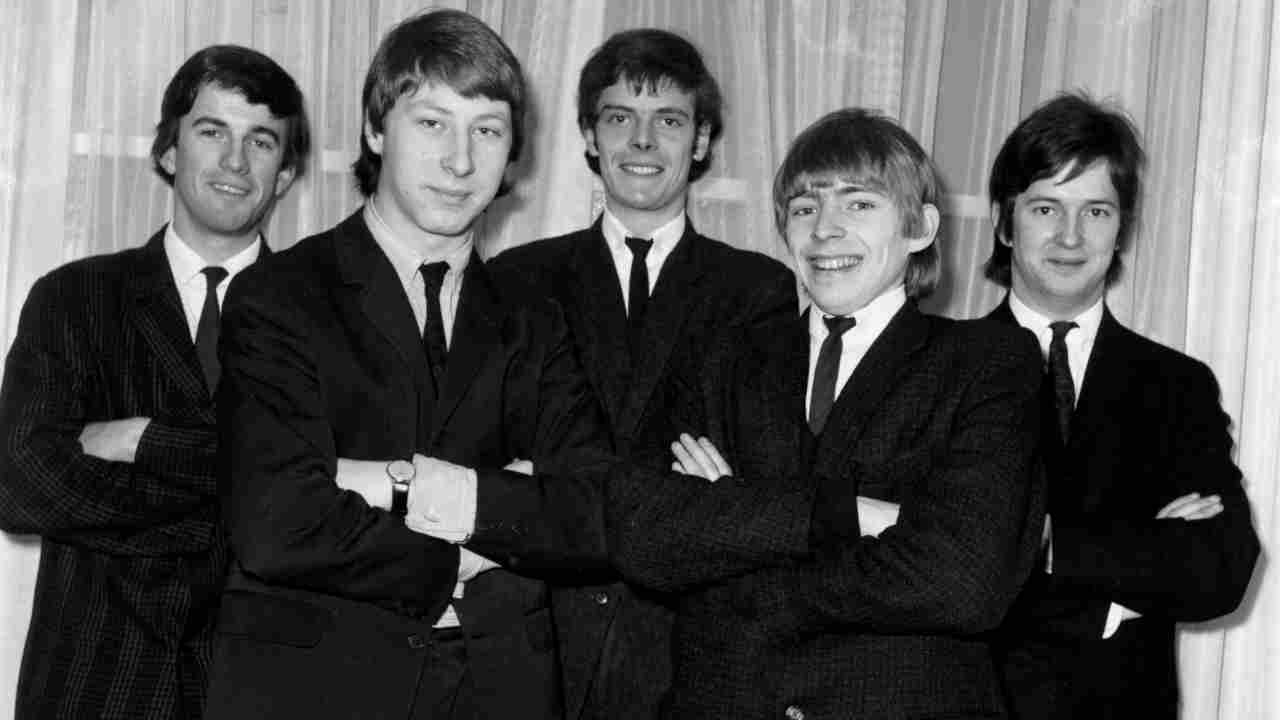

Just weeks earlier, in March ’65, Clapton had made a career move that everybody thought was bonkers. Just as his then band The Yardbirds finally landed themselves a hit single, he quit. Yet it was equally obvious to anybody who actually knew Eric that the split, based on ‘musical differences’, was inevitable. When it came to the blues, Eric was musical and the rest of The Yardbirds, in his view, were cosmically different.

Mike Vernon was a staff producer at Decca Records, and a blues enthusiast who ran a magazine called R&B Monthly with his brother Richard and another blues fan, Neil Slaven. Mike was a regular at Yardbirds gigs in south London.

Just weeks earlier, in March ’65, Clapton had made a career move that everybody thought was bonkers. Just as his then band The Yardbirds finally landed themselves a hit single, he quit. Yet it was equally obvious to anybody who actually knew Eric that the split, based on ‘musical differences’, was inevitable. When it came to the blues, Eric was musical and the rest of The Yardbirds, in his view, were cosmically different.

Mike Vernon was a staff producer at Decca Records, and a blues enthusiast who ran a magazine called R&B Monthly with his brother Richard and another blues fan, Neil Slaven. Mike was a regular at Yardbirds gigs in south London.

“It was very much a ‘band sound’,” he recalls. “Choppy guitars, crisp but mundane harmonica, not stand-out vocals, but the band had a great groove and the young kids really liked it. But they never played a slow blues until [singer] Keith Relf started to suffer with asthma and sometimes he was unable to play the second set, so other people would get up and sing, like Hogsnort Rupert, Rod Stewart and Ronnie Jones. Even I got up a couple of times, and I couldn’t sing for toffee. Eric would say: ‘Oh man, I’m just dying to play a slow blues.’ I’d say: ‘Okay, I’ll get up and sing one.’ ‘What? You can’t sing?’ ‘Well, good enough.’ So we’d do Five Long Years or something like that.”

So Clapton was never able to express himself through the intensity and measured pace of a slow blues, where timing makes the notes you don’t play as meaningful as the ones you do. Worse still, his personal vision was at odds not only with Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky, who was looking for pop success, but also with guitarist Paul Samwell-Smith, who became the band’s musical director and had found that elusive hit single when he heard a song called For Your Love, written by up-and-coming songwriter Graham Gouldman (later of 10cc). On The Yardbirds’ hit recording of it, the lead guitar was buried in the mix. A showdown between Clapton and Gomelsky followed, and then Clapton was gone.

As Keith Relf observed sadly: “Eric loves the blues so much. I suppose he didn’t like it being played badly by a white shower like us.”

Relf didn’t know the half of it, however. For Eric, playing the blues his way was not just a matter of life and death – it really was more important than that. In a painfully honest interview with teen magazine Rave shortly after he’d left, Eric displayed how out of place and detached he felt in the band: “I lived as part of The Yardbirds unit, yet I was completely out of touch with it. I couldn’t speak and be understood. And they couldn’t speak to me either. We just couldn’t communicate… If I hadn’t left The Yardbirds I wouldn’t have been able to play real blues much longer because I was destroying myself.”

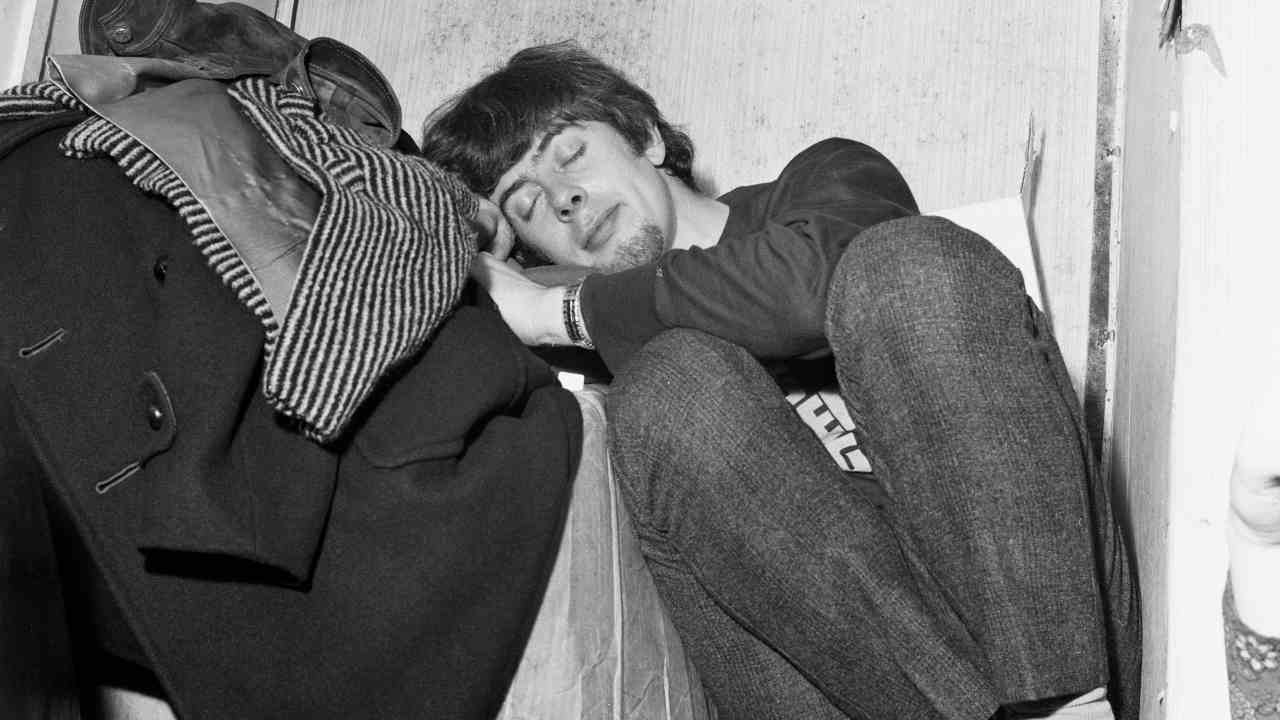

Possessed of a wafer-thin skin, a psychologically bruised Clapton, still only 19, retreated to the countryside, into the care of Ben Palmer, the pianist friend from Eric’s first real group, The Roosters. Equally cynical of the music business, Palmer had chucked it all in to restore antiques and make cabinets. Cooking, talking and listening to music at Palmer’s place gave Eric the chance to catch his breath while he worked out what to do next.

Meanwhile, another blues crusader was struggling. At the urging of Alexis Korner, Macclesfield-born guitarist, keyboard player, singer and harmonica player John Mayall (who as a teenager gained some local celebrity when the Manchester Evening News ran a story about how he lived in a tree house in his mother’s garden) moved down to London in January 1963 and formed The Blues Breakers, who, like Alexis’s own bands, went through a number of line-ups over the next couple of years.

In a sense the first wave of British blues was over; never a pure blues artist, Alexis Korner’s repertoire could just as easily feature a Charlie Mingus tune as a Muddy Waters cover, while Cyril Davies, the real Chicago blues flag waver, had tragically died in January 1964. All the other blues-inspired bands, such as The Rolling Stones, Yardbirds, Pretty Things and the rest, had diverted down a Bo Diddley/Chuck Berry-driven pop R&B route. This left John Mayall trying to find a formula for commercial success while still deeply committed to blues sensibilities. Two Mayall-penned singles for Decca – Crawling Up A Hill (May 1964) and Crocodile Walk (April 1965) – failed to trouble the chart; a similar fate awaited a live album recorded in December 1964: John Mayall Plays John Mayall, recorded at Klooks Kleek, a club above the Railway Tavern pub in West Hampstead, next door to the Decca studios.

Apart from the lack of chart success, what was holding Mayall’s band back as a blues outfit was the lead guitar. Roger Dean had replaced former Cyril Davies guitarist Bernie Watson. Both were accomplished players who could knock off some Chuck Berry or T-Bone Walker licks, but Dean was actually more comfortable in Chet Atkins mode, and neither could get to grips with the stinging, single-string playing styles of a BB or Freddie King.

However, unlike The Yardbirds, who struggled when they backed Sonny Boy Williamson (“Those boys want to play the blues so bad – and they play the blues so bad,” was his alleged famous comment) The Blues Breakers made a pretty good fist of backing T-Bone on his 1965 UK tour.

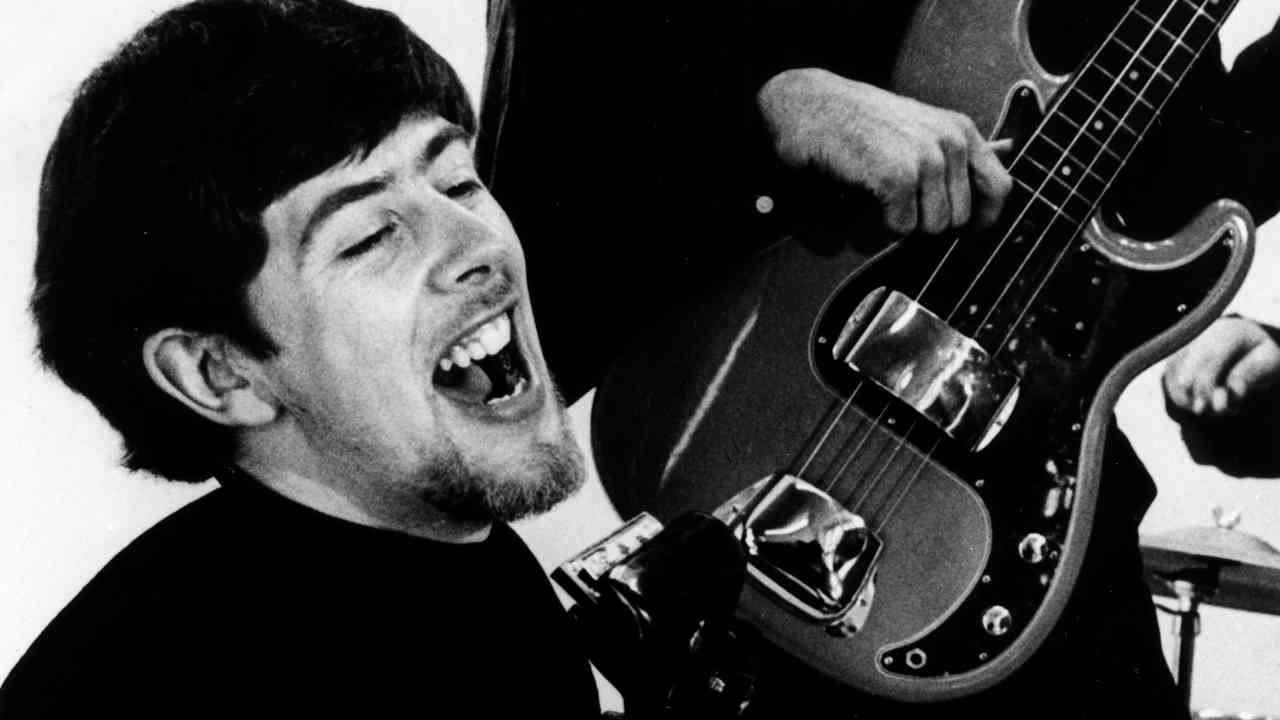

On March 28 the tour rolled into Nottingham. It was here that John Mayall gathered his rhythm section of drummer Hughie Flint and bassist John McVie around a jukebox and said: “Listen to this.” What they heard was Eric Clapton stretching out on Got To Hurry, the B-side of For Your Love. “John asked us what we thought – and of course we said that it sounded pretty good,” Flint recalls . “John said: ‘That’s Eric Clapton. And he’s just left The Yardbirds. Should we ask him to join?’ To which we replied: ‘Yeah.’”

Eric actually took some persuading when Mayall phoned. But “one day, I got in the van and there he was”, Flint remembers.

With no rehearsals, Clapton played the first gig with Mayall in early April, and straight away Mayall knew he had made the right choice: “He was the first guitarist I’d heard who had it – you know, the elusive ‘it’,” the bandleader reacalls.

Eric moved out of Ben’s place and in with John and Pamela Mayall and their four kids. Not feeling part of the family, he squirrelled himself away in a tiny room at the top of the house where he stayed most of the time, listening to Mayall’s vast record collection and practising guitar.

The arrival of Eric gave John the chance to further develop the band along Chicago blues lines – he put away his own guitar and concentrated on keyboards and harmonica. Almost as soon as Eric joined, they recorded five songs for the BBC radio show Saturday Club, one of which was Freddie King’s Hideaway, which Eric had heard on the 1962 album Let’s Dance Away And Hide Away with Freddie King. But it wasn’t just the music that grabbed Eric’s attention on that occasion – on the front cover, Freddie King was clutching a Gibson Les Paul.

Eric’s first electric guitar had been a double-cutaway Kay Red Devil (actually a yellowy/pink sunburst colour, which he’d covered in black sticky-backed plastic) purchased in 1962 with financial assistance from his grandparents. It was a copy of another Gibson guitar, the semi-solid ES335, one of which Eric later played for real with The Yardbirds, on loan from Yardbirds rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja. Eric’s main guitar during the Yardbirds years was a red Fender Telecaster played through a Vox amp, producing a sound which Mike Vernon describes politely as “pissy”. Jeff Beck initially played Eric’s Telecaster when he took over in The Yardbirds (“A terrible guitar,” he said later), but Eric retrieved it for his early gigs with Mayall.

Then Eric spotted a magnificent flame-top maple 1958-60 Les Paul in Lew Davis’s music shop in London’s West End and snapped it up for around £120, which was relatively cheap because the heavy Les Pauls had fallen out of favour in the face of the challenge from the ES335 and models from Fender, Rickenbacker, Gretsch and Guild. Now he had a guitar with a sound that was very far from pissy: its powerful ‘humbucking’ pickups could drive an amp well into uncharted realms of distortion and sustain.

But which amp? Freddie King used a meaty Fender Bassman, rare and expensive in the UK. Eric’s limp Vox amp couldn’t handle it.

The answer came not from the hallowed halls of American guitar manufacture, but from a small music shop in west London. Jim Marshall was the boss, Ken Bran his repairman. Requests from musicians for more powerful amps had led Ken to build a UK version of the Bassman. When guys plugged their shiny new Fenders into the new Marshall 45-watt, 2x12 combo, the results were great. When Eric plugged in his Les Paul the sound was astonishing: a thick, creamy, gut-wrencher that trumped anything heard in the States.

Eric appeared settled. He had the right equipment to match his aggressive style, all the records he could absorb, and plenty of gigs all over the country, playing exactly the kind of music denied him in The Yardbirds – and establishing his reputation as the hottest guitarist on the scene. Audiences at Blues Breakers gigs were swollen by the arrival of Clapton’s own fan club, and it was around this time that the legendary graffiti declaring ‘Clapton is God’ began to appear around London. In his autobiography, Eric says he was very much torn by the growing acclaim: “I was a bit mystified by this and part of me ran a mile from it. I really didn’t want that kind of notoriety… Another part of me really liked the idea, that what I had been fostering all these years was finally getting some recognition.”

Although Mayall was building up a reasonable head of steam on the club circuit, the search for a hit record continued. After the failure of his recordings for Decca, he’d been dropped by the label. In the summer of ’65 he signed with Immediate Records, a new label set up by Tony Calder and Rolling Stones manager Andrew Oldham. With Jimmy Page as the house producer, The Bluebreakers recorded I’m Your Witch Doctor and Telephone Blues, put out by Immediate as a single with the former as the A-side and the latter on the B-side. A third track, On Top of the World, went unreleased until 1968, along with some unremarkable blues noodlings recorded by Jimmy and Eric at Jimmy’s house, where Eric had stayed after a nearby Mayall gig.

Up to that point there had been sporadic hints on record of the Eric Clapton to come – tentative and reverential solos on the live Yardbirds album with Sonny Boy Williamson (Mr Downchild and 23 Hours Too Long), and the track that first attracted Mayall. But Jimmy Page allowed Eric to begin unleashing the power he now had at his command with the Gibson/Marshall set-up – striking single-note feedback solos (an idea he may have copped from Jeff Beck) on …Witchdoctor and On Top Of The World, and signature soloing on Telephone Blues.

Which is where we came in. Jimmy Page recalled: “I remember when we did I’m Your Witch Doctor, he had all that sound down, and the engineer, who was co-operating up to that point, but was used to doing orchestras and big bands, suddenly turned off the machine and said: ‘This guitarist is unrecordable!’ I told him just to record and I’d take full responsibility.”

And so John Mayall could have been forgiven for thinking that finally he had a regular and stable top-flight blues outfit for whom the only way was up. But he hadn’t reckoned with the wayward spirit that was Eric Clapton. Eric was no guitar grunt, but an intelligent and curious man who was interested in art and culture. He fell in with a group of musicians and poets who between them concocted the sort of mad plan that comes from spending too much time in a fug of dope smoke.This was to be Eric’s ‘gap year’, on the road with his mates in a band they called The Glands.

Setting off in September, this “hare-brained scheme” (as Mayall calls it, tersely) ended prematurely and slightly dangerously for Eric in Greece. Mayall, meanwhile, was left trying to hold it all together with a succession of replacement guitarists that included John McLaughlin and Peter Green. By the time Eric phoned John to claim his job back in late October – instantly agreed to by Mayall – bassist John McVie had been sacked for having one drink too many, and Eric found himself in a Mayall band that also included Jack Bruce on bass for about a dozen gigs before Jack was poached by Manfred Mann.

Nothing came of the deal with Immediate. Mayall was unhappy with the arrangements, and approached Mike Vernon to see if Decca would give him another chance. Vernon said to Hugh Mendl at Decca: “You really need to have another look at John Mayall And The Blues Breakers. Now they’ve got Eric Clapton on guitar they’re going to be big-time – they’ve got an enormous following, they’re working five or six nights a week.” Mendl said: “If you think it’s the right thing to do I’ll push it through. Go ahead, and we’ll get contracts drawn up.”

While that was going through, Vernon had an idea. “They weren’t under contract to Immediate any more, and as well as R&B Monthly, me, Richard and Neil had this little fledgling label called Blue Horizon where we produced only 99 copies of each record – to avoid purchase tax – and we sold by mail-order only. We were thinking of starting up another label called Purdah. So I said to John and Eric: ‘Before we make this record with Decca, how do you fancy making something for Purdah?’ They thought it was a great idea, and decided to do Bernard Jenkins and Lonely Years as a duo like an old Chicago record.

“We talked it through, and I suggested we just use one microphone. We went into the original Wessex studios in Old Compton Street, up on the third floor right in the middle of Soho. We did it in one afternoon. I think it only took a couple of hours. We put an old microphone on a boom stand, and John and Eric set up, Eric a bit further away from the piano. We moved the mic around until it sounded right and then we said: ‘Let’s go.’”

This wasn’t the first time Vernon had worked with Eric in the studio. Vernon and Giorgio Gomelsky had co-produced the first Yardbirds demos, back in February 1964, and also Vernon lit up Eric’s life by asking him to play lead guitar on two studio tracks with Otis Spann and the Muddy Waters Band.

Eric had become obsessed with the character of Bernard Jenkins, the caretaker in Harold Pinter’s eponymous play. He bought the script, knew it off by heart, and saw the film The Caretaker, with Donald Pleasance as Bernard Jenkins, several times. Its themes of isolation, the inability to communicate and the way the characters attempt to manipulate and deceive each other all resonated strongly with the complex personality that was Eric Clapton. Musicians have testified that back in those early days that you never quite knew where you were with Eric. He could be your best friend one day, and blank you the next. Mood swings that became as well known as his frequent changes in appearance.

For Mike Vernon, Lonely Years was “the finest effort Eric ever put on record. It just sums up exactly what Eric was about at that time – that real down-home feel. That record was the closest I came to a real Chicago sound. As I said, we only pressed 99 copies, but in three months we sold a thousand. I think I actually sold the masters to Immediate, funnily enough. I was quite friendly with Tony Calder. Decca didn’t know what was going on. There was no need for them to.”

Praise for the record came from an unexpected source: Paul Oliver raving about it in Jazz Monthly. Oliver was normally associated with an older posse of critics, journalists and academics who felt they’ad found the blues and it was their domain, their property. And, Vernon says, they felt that “these young, white, long-haired buggers had no right to it. But I was not dim-witted as to think that John Mayall and Eric Clapton were not the real thing, to think they were just a nasty smell that would go away next week. It became an extremely pungent nasty smell for a very long time – and thank God for it.”

The deal with Decca Records was struck, and it was agreed to forget about the singles market and go for a studio album. And, importantly, on that album, Mayall says, “I wanted to capture the sound of the band live on stage”.

That aim of Mayall’s was laudable, Mike Vernon says, but adds that it was also “very, very difficult because the acoustics of live venues vary so much between studios. And back then studios had written rules about ‘you can’t do this and you can’t do that’ coming from men in white coats. Until Gus Dudgeon arrived, and then it was all tight trousers, bright socks and sneakers.”

After being sacked from various jobs, Dudgeon started out at Decca studios as tea boy and, despite having no experience at all, progressed to sound engineer by initially demonstrating that he knew how to use and repair a tape recorder. In 1964 he had been the engineer on The Zombies’ hit She’s Not There, and in Dudgeon Mike Vernon soon spotted a kindred spirit. But as Mayall and his band set up in Decca’s Studio 2 to start recording the album, even Dudgeon became worried.

Vernon describes the set-up on the first day of recording, in March 1966: “If you can imagine the control room window looking into the studio, immediately opposite is the drum booth, enclosed from about shoulder height if you’re sitting at the drums, across the sides and over the top. John McVie [back in the band from January] was sitting to the right of that with his amp in front of the board, with the bass drum behind it. To the right of the control room was where the organ was set up and where John did the vocals. We dressed up the vocals with reverb, delays and things like that. So bass, organ, drums, that was all fine.”

But not from drummer Hughie Flint’s point of view: “I was told to play on the hi-hat as much as possible,” he says, “not to do crash cymbals unless absolutely necessary.”

The real problems began when it came to the guitar. “We all knew,” says Vernon, “that the guitar would be the main issue. Except Gus, who hadn’t seen the band play live. And he had a real shock when Eric arrived, plugged in, turned everything on and started playing. Gus almost fell over. He looked at me and I knew exactly what he was thinking: ‘Jesus Christ, we’re gonna have to turn that down!’ And of course that’s when the ‘discussions’ started. It was never an argument, but it was definitely a ‘discussion’ about how the hell we were going to record this. The sound was going everywhere because it was so loud. The studio wasn’t that small, you could get a brass section and background singers in there.”

But if the idea was to capture the live sound of the band, then Eric was going to play exactly as he did live, which was loud. In fact although Eric had more recording experience than anybody else in the band, he was quite sniffy about recording the blues in a studio at all, much preferring to do live recordings to capture the passion on the night.

“We had him turn the amp towards the wall and angle it slightly towards the control room,” Vernon says of their efforts to find a way round the problem caused by the volume Eric insisted on playing at, and the ‘bleed’ on to the recording of the other instruments that it lead to. “Then we put half-transparent boards up all around it and put a microphone about two to three feet from the amp. Then we draped a huge great blanket over the top of the stack and over the mic in an attempt to actually keep the sound in there. So when they started playing, it sounded reasonably akin to how they sounded live. But the guitar was in everything. We recorded on four-track, so when you opened up the drums you definitely had guitar in it. Same with the bass and vocals. But John actually did some of the vocal tracks over again, so the guitar didn’t become an issue.

“The reason for angling the amp was to make sure all the sound didn’t come straight out into the room, otherwise we would have stood no chance at all. We had no more isolation rooms that were usable. Actually, we had one room at the end of the studio, with a door and a glass window, that doubled as a vocal booth and a tape store room, but if we’d put it in there Eric wouldn’t have really heard his amp – he would have needed to wear headphones, and he didn’t want to do that. He said: ‘I want to play as if I’m doing a gig. I want to be standing right next to the amp. I want to be able to hear what I’m doing and what everybody else is doing.’ A tall order in 1966. Gus was going: ‘We can’t do this, man. We can’t do it. We’re not allowed.’ So I said: ‘Come on, we need to work together with these guys, and we’ll get a great sound. And when we do, they’ll play and it will be wonderful.’

“It took a while to get a sound that everybody was happy with, especially Eric, but everybody had to take on board that we were going into an unknown era. Nobody in Decca studios had ever witnessed somebody coming into the studio, setting up their guitar and amp and playing at that volume. People in the canteen behind the studio were complaining about the noise. Normally they’d never hear it, but this was travelling around the studio complex. People were saying: ‘What the bloody hell is that?!’ and coming to see what was going on.”

(Arguments among guitar freaks have raged down the years as to whether or not Eric used a Dallas Rangemaster treble booster in the studio. Well, the answer is no, he didn’t – and that’s straight from the source.)

As for the songs that were to appear on the album, Vernon recalls: “We probably didn’t do as much planning for the album as we should have done. My discussions were directly with John. He chose the material.”

The album was supposed to reflect the band’s live set at the time and, with its mixture of Chicago blues covers and Mayall compositions, for the most part it did. The Blues Breakers had a large contingent of followers at the Flamingo Club, a posse of black American GIs who, as fans of Jimmy Smith, were into the organ-driven bands of Georgie Fame, Brian Auger and Graham Bond, and were actually more appreciative of Mayall’s organ playing than of what Clapton was doing. So Mayall wanted to include the sounds of Mose Allison (Parchman Farm) and Ray Charles (What’d I Say).

Vernon, though, had his doubts about the second one: “I do remember saying that I wasn’t too keen on doing What’d I Say – you’re up against a Ray Charles record which was pretty huge. But John said they did it live and people liked it, and it gave Hughie a chance to do a drum solo – which, under my breath, I said: ‘Oh no’. But I don’t think the drum solo was Hughie’s idea, he didn’t see himself as a solo drummer.”

Indeed it wasn’t Hughie’s idea. Looking back, the drummer says: “I was a bit apprehensive about doing the solo on the recording. On stage you can get away with anything and it sounded fairly exciting. But I wasn’t that happy with it at the time. I was never a great soloist.”

The version of Double Crossing Time that appears on the album was actually recorded for Immediate Records prior to Christmas ’65 with John Bradley on bass, brought in quickly to replace Jack Bruce who’d jumped ship to Manfred Mann on the promise of vast riches (which of course never materialised). John and Eric were somewhat pissed off by Bruce’s departure, and together wrote Double Crossing Man, later changed to Double Crossing Time. Eric’s solo on that track, however, was dubbed on during the recording of the album.

One song which was definitely not in Mayall’s live sets was Robert Johnson’s Ramblin’ On My Mind. Recorded for the album as a sparse, plaintive guitar-and-piano track, it’s notable for being Clapton’s debut vocal performance on record. He later told US music critic Peter Guralnick: “I don’t think I’d ever heard of Robert Johnson when I found the record… I was around 15 or 16, and it was a real shock to find something that powerful… What struck me about Robert Johnson’s record was that it seemed as if he wasn’t playing for an audience. It didn’t obey the rules of time or harmony or anything. It led me to a belief that here was a guy who really didn’t play for people at all, that his thing was so unbearable for him to have to live with that he was almost, like, ashamed of it, you know. This was an image, really, that I was very, very keen to hang on to.

“I’d been singing and playing in that style for so long, it was really just a question of turning the tape machines on. The leap came in accepting that this thing was going to go onto plastic and would be recorded. Accepting that took a lot of convincing from John, who really kept having to tell me that it was worth it.”

The contributions of saxophonists Alan Skidmore (tenor) and John Almond (baritone) and trumpeter Derek (wrongly credited on the sleeve as ‘Dennis’) Healey deserve honourable mentions. “I used to see Jimmy and Alan Skidmore in the jazz clubs, so I brought Alan in for the recording,” Mayall recalls. Many of the original Chicago blues bands used horns both on stage and on record, and John himself had used Nigel Stanger on sax for the previous live album. But the white blues purists were aghast. Mayall had little time for “people pretending to know your music better than you do. We were learning from people we admired and being as true to the music as possible.”

Hughie Flint acknowledges that the band played well on the album, but concedes that “it was Eric who shone”.

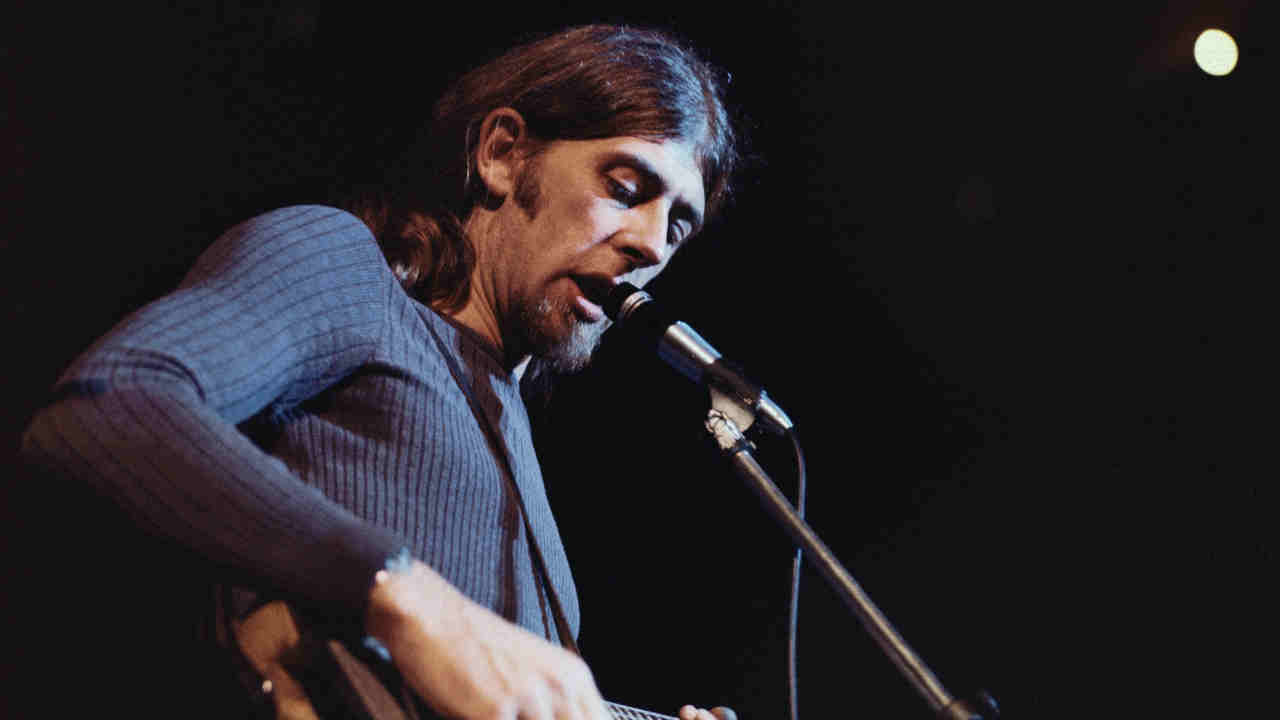

The album was a unique moment in time – a combination of Mayall’s intellectual sincerity, and Clapton’s savage intensity and emotional truth that ripped through all the key solos: the two instrumentals Hideaway and Steppin’ Out, Key To Love, Double Crossing Time and of course the monumental Have You Heard. Clapton detonated a neon explosion of noise and notes, cutting, biting, trebly and harsh, angry, passionate, a firestorm of blues runs, intense yet controlled; a music caught in the crosshairs of a young man’s frustration and anger, a man gripped by a psychic disturbance that he felt could be exorcised only through a Gibson/Marshall set-up. The simple skeleton framework of the blues allows acres of freedom inside. Neil Slaven wrote in his original sleeve notes: ‘…On his best nights Eric can make time stand still.’ And on the album, in places he seems to produce the same effect.

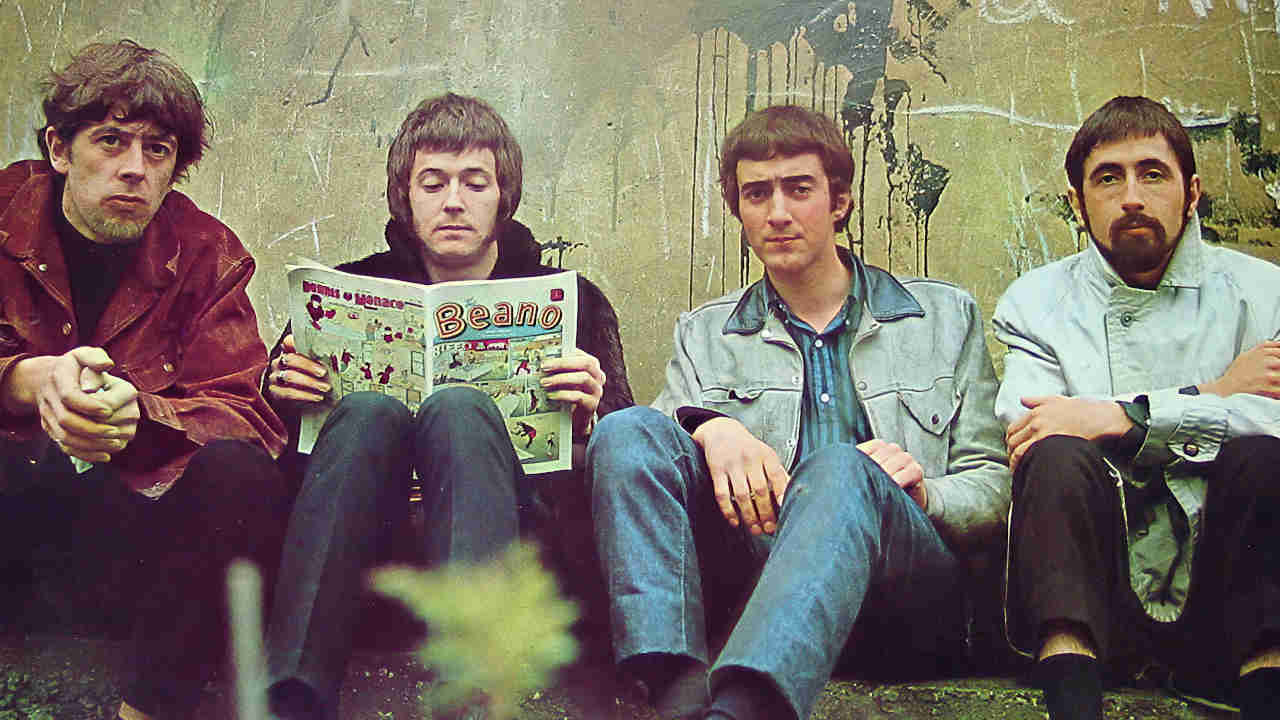

The cover photograph for the record, which inspired the nickname the ‘Beano album’, was shot by Decca Publicity Art Dept. photographer David Wedgbury. Various locations were scouted, but before Wedgbury could take his shots in front of the wall he had to scrub off graffiti helpfully daubed on it by the band. Harold Wilson was the Prime Minister at the time, and also ‘A Nit’ according to the political analysts of The Bluebreakers – you can just see the remnants of the word in the top right-hand corner of the cover.

Eric had always loved comics, the Beano in particular, and feeling bored and unco-operative he just started reading the one he’d bought that morning. One of the comic’s leading strips was Lord Snooty and his pals. Which in a way described The Blues Breakers. By his own admission, Eric regarded himself as a cut above any other white blues guitarist, and actually wrote the words ‘Lord Eric’ in Biro on his very first guitar. And while John was the bandleader, Eric was the star – and knew it. Nobody called Eric ‘Lord Snooty of the blues’, but at that time he probably was.

Mayall never saw this album as the route to taking the band to the next level. “You would be foolish to think an album would do that,” he offers. “I have never recorded albums in that way – more as stepping stones. The priority is to produce some good blues music and get it down the way you want it. Where it goes from there is anybody’s guess.”

Hence it came as a massive shock when the Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton album, as it was titled, released in July 22, 1966, extraordinarily reached No.6 in the UK chart (a gritty blues album flanked by the likes of The Beatles, Herb Alpert And The Tijuana Brass, The Beach Boys and The Sound Of Music soundtrack) and enjoyed a chart stay of 17 weeks. Quick as a flash, Eric was phoning John to ask for more money. John was in no mood to be magnanimous, however, and brushed Eric off with a curt: “You got a session fee, the same as everybody else.” Which is hardly surprising – after all, even by the time the first copies of the record were coming off the presses, Eric had dumped The Blues Breakers to go off and form Cream with Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker.

Even as he lined up for the photo-shoot for the Beano album sleeve, Cream had already been rehearsing in secret. Kinks bassist Pete Quaife recalls Eric talking to him about forming a band as far back as Christmas 1965. In the same month that the album was recorded, Clapton was so self-assured in his ability that he was telling Melody Maker he was thinking of quitting the UK altogether and moving to Chicago because there was nothing for him at home. Hughie Flint recalls some BBC sessions Mayall’s band did when Eric had to play quietly (preserved BBC recordings of Crocodile Walk and Key To Love spring to mind), and “where the contempt for what he was being asked to do just oozes out of it. Even on live gigs Eric could be very badly behaved and hardly play. Thankfully it didn’t happen very often, although sometimes he wouldn’t turn up at all and we would play as a trio.”

Clapton’s guitar playing on the groundbreaking, now iconic Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton album encapsulated everything about his development as a musician: his disrupted childhood, his disrupted adolescence, and the discovery of an art form, a mode of expression into which he could sublimate all his anger, his sense of isolation, playing combinations of notes which for him expressed more than words ever could. And all this tied to a knowing that, while he started out as Mayall’s student, the band was now trailing in his wake and he knew he needed to move on. The short period that bassist Jack Bruce had spent in Mayall’s band alongside Eric had shown him what was possible, where Eric could take this music and make it his own.

Nothing that John Mayall has done since – and Clapton only with Cream – has quite had the reach down the years and across rock music as the hugely influential Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton album. It opened up the world of the blues to young white audiences, announced the arrival of the modern guitar hero, and kick-started the cult of virtuosity, encouraging young musicians (and not just guitarists) to become accomplished players. For most it was the first time they had heard and felt the power of a Les Paul through a cranked Marshall, a sound that helped define rock for decades afterwards. It saved the then-ailing Gibson guitar company, and put the then-new Marshall amplification on the international map – and on subsequent generations of guitarists’ wish-lists.

Yet, as Mike Vernon points out, the album itself has hardly been acknowledged, certainly nothing like its legend and iconic status today might lead one to expect. “It would be a fascinating project for somebody to find out exactly how many units this album has sold in all the formats and different releases and in the different regions. Everybody wants to talk about this album, so many people own it and it has to rank among the top 10 influential albums ever recorded. But it has never won any awards, doesn’t have silver or gold record status, isn’t in any Hall Of Fame. And because I was a salaried staff producer at Decca I never got a royalty. I never made a bean-o.”

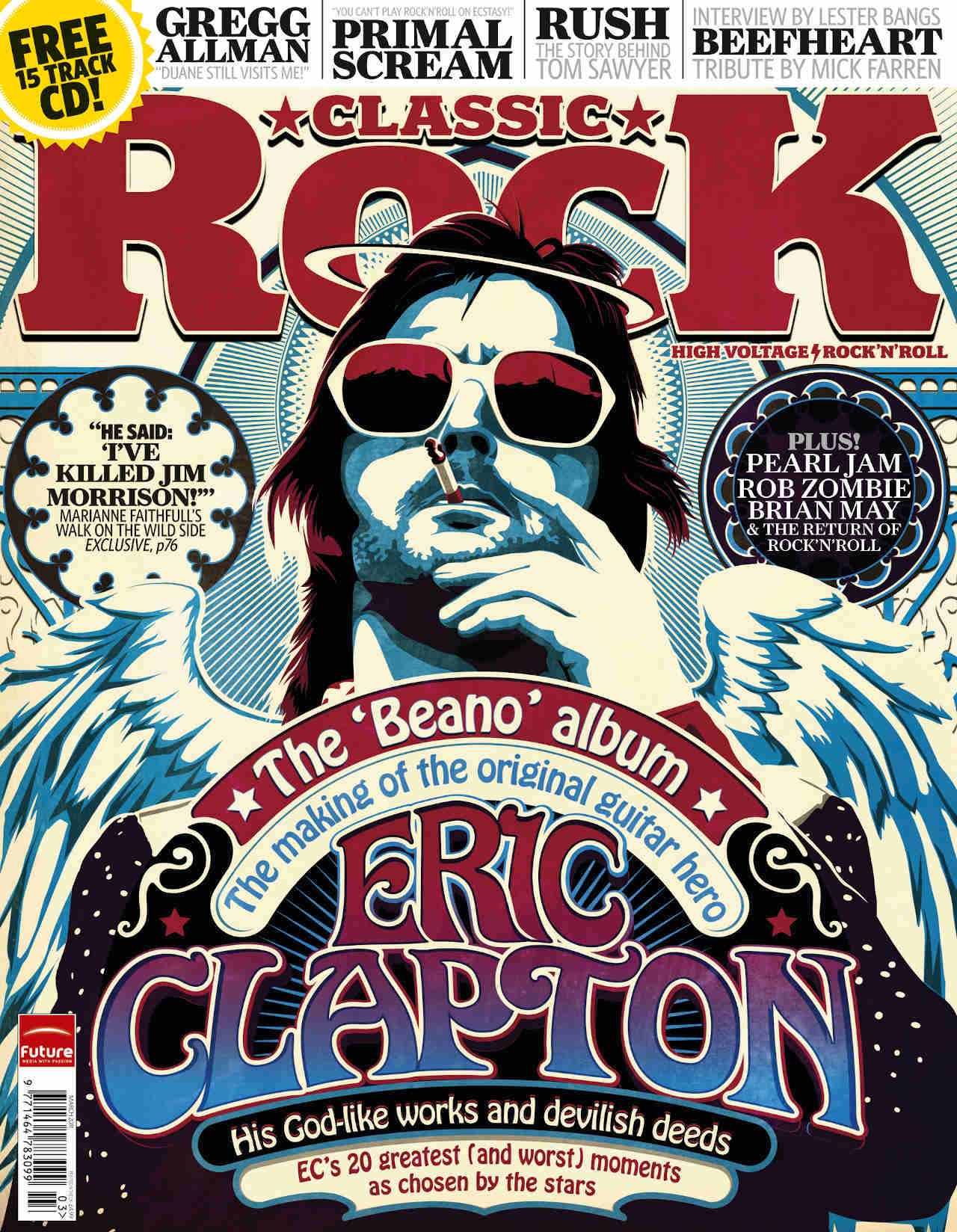

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 155, February 2011