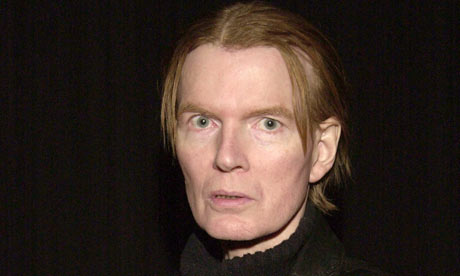

With the death of Jim Carroll last week, America has lost one of its singular and most under-rated poetic voices. As depicted in his most popular work The Basketball Diaries, Carroll grew up on New York's Lower East Side, the son of three generations of Irish-American bartenders, with the fair Irish looks to match. He was also an unlikely poetry prodigy and a man of contrasts: at the age of 12 he started keeping a diary that documented his dual teenage existence as an-all star basketball player at an elite private school, and his emerging heroin addiction and the street life that surrounded the junkie scene.

Inspired by the likes of Rimbaud and Frank O'Hara, in 1965 he began attending workshops at St Mark's Place and published his debut Organic Trains a year later at the age of 16. Extracts from The Basketball Diaries appeared in the Paris Review - a huge achievement for a 16-year-old, especially one who was also occasionally working as a Times Square rent boy and mugger to finance his heroin addiction.

It was poet Ted Berrigan who took Carroll under his wing, introducing him to the likes of Burroughs and Kerouac, who remarked that "at 13 years of age, Jim Carroll writes better prose than 89% of the novelists working today." Carroll's ascension coincided with a cultural explosion centred on downtown Manhattan in the late 60s/early 70s, an era that spawned Andy Warhol, Velvet Underground, Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. Carroll was feted by them all - drinking with Bob Dylan one day, fending off the advances of Allen Ginsberg the next. It was a time later documented in arguably his strongest prose collection Forced Entries: The Downtown Diaries 1971 – 1973.

For someone so effortlessly cool and well connected, it was little surprise when Carroll later enjoyed a musical career that, financially at least, was surely more lucrative than poetry. Patti Smith first encouraged him to turn his poems into lyrics and Keith Richards helped secure a record deal, but rock music was only ever really a sideline for Carroll, a welcome distraction. It was clear that his heart lay in the internal world of literature and his work continued to return to certain core themes: religion and catholicism, dreams, addiction, New York, childhood and adolescence, death, survival.

Carroll's poetry output was slim - he published just three collections (Living At The Movies (1973), The Book Of Nods (1986) and Fear Of Dreaming (1993)) over 20 years - yet everything he published was incisive, illuminated and humane. He was one of few contemporary poets to cross over into the mainstream when MTV invited him on air; he also read his work between bands at the 1993 Lollapalooza tour and appeared on MTV again in 1995, reading "8 Fragments For Kurt Cobain" from Void Of Course in his recognizable downtown tones, of which he once wrote "My voice has a quiver / A quiver is where you keep arrows until you shoot them".

A sense remained that heroin may have prevented Carroll from reaching his fullest potential - that he wasn't quite "the Dylan of the 80s" that some critics had predicted. Yet it was also this outsider status that afforded him a unique poetic standpoint. "It's sad this vision required such height," he wrote. "I'd have preferred to be down with the others." Ultimately the facts speak for themselves: his readings continually sold out, his influence upon writers such as Irvine Welsh and Tony O'Neill and film-maker Harmony Korine is evident and when he died at his desk last week, he left behind a solid body of work that is as representative of late 20th century American literature as Warhol was to its art and the Velvet Underground to its music.