British jihadist Mohammed Emwazi was imprisoned by Greek authorities on his way to fight in Syria but was released to continue his journey, a militant has claimed.

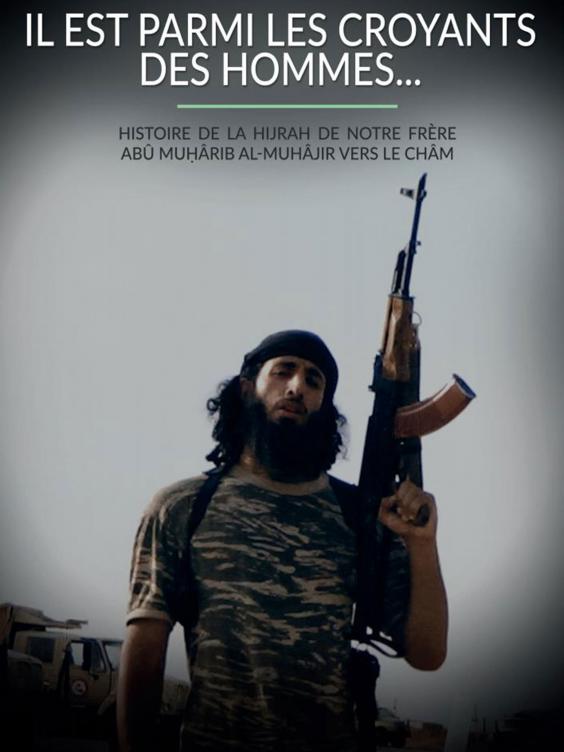

Isis has released a lengthy account describing how the former London student reached its territories, where he became known as "Jihadi John" after appearing in a series of gruesome execution videos.

A fellow militant claimed he and Emwazi posed as migrants of varying nationalities while travelling through six countries on their way to Syria, having left England hiding in the back of a lorry.

“The controls are much stricter entering the UK than leaving,” he noted.

Writing Isis’ French language propaganda magazine, the fighter described their alleged journey from Britain to the Middle East.

Calling 27-year-old Emwazi by his war name of Abu Muharib al-Muhajir, he recounted making detailed plans to evade border checks in the belief that they would be immediately arrested by counter-terror police at British airports, railway stations and ports.

The unnamed militant said he had been caught at the Turkish border and deported back to the UK on a previous attempt, while Emwazi was under surveillance after being questioned by MI5 on suspicion of attempting to fight with al-Shabaab in Somalia in 2010.

The pair reportedly departed in August 2012 carrying a rucksack and €30,000 (£23,400) in cash, paying people smugglers to conceal them alongside migrants in a lorry crossing the Channel before it drove them onwards to Belgium.

They used their real passports instead of the fake French ones they bought to take flights to Albania, the jihadist wrote, saying they were “without danger or fear that British intelligence services would be alerted" by their Belgian counterparts.

Emwazi and his co-conspirator used a brief stop in Brussels to eat a “lovely” breakfast and prepare for the trip onwards, including shaving their beards off in a hotel to change their appearances.

The militant recounted how they prepared a cover story that they were planning to journey to Corfu, as Albania was “not really a tourist destination”, and stayed in hotels in Tirana while Isis facilitators co-ordinated by a militant known as Abu Usamah organised their onward passage.

A man using that pseudonym was named as an Isis “financier and facilitator” by the US in 2014, when the American treasury said he had been paying for foreign fighters to join jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq for at least six years.

After a delay of several weeks in Albania, the account claimed Emwazi and his friend paid €1,000 (£800) each to people smugglers to guide them across the mountainous Greek border to Kastoria.

Having taken a taxi to Thessaloniki, a Bangladeshi man directed them to a smuggler who took $200 (£140) each to drive them to the Turkish border under the cover of darkness.

The jihadists were dropped off to travel the remaining distance on foot and had been walking for hours when a Greek border patrol spotted them.

Emwazi discarded all their passports and fake documents as the armed officers approached, the militant said, and claimed to be a migrant from Burma as they were questioned at gunpoint.

The writer, who claimed police believed he was Zimbabwean, described them being searched and locked up in a cell “not exceeding ten square meters…infested with mice and mosquitos” alongside two Somali men.

“This situation lasted for four days with us not have a clue on further events or any information,” the jihadist claimed.

“Every day we repeated to the guards that we just wanted go to Turkey and we had no intention to stay Greece.”

On orders from their superiors, the militant said police freed them and their fellow prisoners on the fourth night into a waiting van that drove them to the Evros River, which forms part of the Greek Turkish-border.

The pair crossed the water on a smugglers’ boat and despite being stopped, photographed and fingerprinted by Turkish police on the other side, were again let go after claiming they were Palestinian asylum seekers.

On the last leg of the journey, the jihadist said he and Emwazi took a bus to Istanbul and received orders from Abu Usamah on how to reach Syria, finally crossing at Bab al-Hawa with the help of Isis fixers.

“Praise be to Allah that reaching Sham (Syria) at that time was easier than nowadays,” the extremist wrote. “The rest is history.”

Emwazi, who was born in Kuwait but grew up in Britain, has been eulogised extensively by Isis since he was killed by an American drone strike in Syria in November.

The latest article appeared in the Dar al-Islam propaganda magazine alongside pieces praising the Brussels bombings, championing life in the “caliphate” and giving tips on how to avoid online surveillance.

The 8,000-word account of Emwazi’s supposed journey appeared to be aimed at encouraging more recruits to travel to the so-called Islamic State from the UK and other European countries, and instruct them on how to evade detection.

It was prefaced by a message urging followers to learn lessons from Emwazi’s “hijrah” (migration) and praised his contribution to the “elevation of Islam”.

He is believed to have joined Jabhat al-Nusra, then a subsidiary of al-Qaeda’s “Islamic State in Iraq”, before the groups merged to become Isis.

Emwazi, whose true identity was initially unknown, first appeared in the propaganda video showing the execution of James Foley in August 2014, before featuring in footage showing the deaths of British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning, and other Western hostages.

He was identified by the media in February 2015 and was killed in a drone strike nine months later.

In January, a separate tribute to Emwazi in Isis’ English-language magazine Dabiq said he died as his vehicle “was targeted in a strike by an unmanned drone in the city of Raqqa, destroying the car and killing him instantly“.

David Cameron said British and American intelligence agencies worked ”literally around the clock“ to track Emwazi down, calling his death “the right thing to do”.

The account of his journey to Syria came as calls for increased security co-operation between European nations continued in the wake of the Paris and Brussels attacks.

James Clapper, the US Director of National Intelligence, said American authorities wanted to “provoke more sharing” within the EU amid reports of new terror plots.

A spokesperson for the Home Office said it draws on Europol databases and the Schengen Information System to track possible terrorists, as well as working on a directive giving law enforcement powers to track suspects into and around Europe.