This is part of a series, This American Carnage, from Charlie Lewis, who is reporting from America on the 2024 US presidential election.

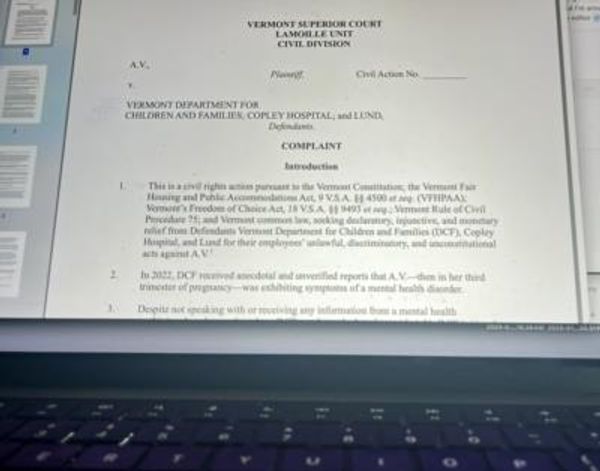

“Jeff Bezos is chickens**t, but we’re not; here’s our presidential endorsement.”

So reads the headline on the Pittsburgh Union Progress (PUP)’s editorial endorsement — and for the record, it has gone with Harris.

It’s the only choice for us. We’re a publication produced by working people on strike — for more than two years, now — and the first Trump term was not good for working folks … We expect a second term would be worse.

But the big reason for our endorsement: The level of our dysfunction is getting out of hand. It’s going to kill our communities. And it’s happening because one person wants it that way. We can begin the long process of cooling down on Tuesday.

Tuesday’s almost here, but the staff of PUP have been on strike from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette for over two years. The strike came on gradually then suddenly, after management imposed unilateral changes in conditions and healthcare on editorial and other staff. This change in the working relationship coincided with the paper’s editorial shift to the right, and these tensions became public when Gazette publisher and editor-in-chief John Robinson Block hopped on Trump’s private plane in 2016.

Journalist Steve Mellon has covered the Pittsburgh area for more than three decades, first with the now-defunct Pittsburgh Press, before joining the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in the late ’90s. Since the strike commenced, he’s been a writer and photojournalist at PUP.

Mellon and his family arrived in Pittsburgh in 1989. “Most of the steel facilities [surrounding Pittsburgh] were already gone by then,” Mellon tells Crikey, and the few remaining were beginning to close. “I got here on a Monday, and by the Wednesday I was touring this massive empty steel mill in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, about six, seven miles from here.”

Touring the mill built like an “airline hanger”, Mellon came upon workers’ abandoned protective gear and personal effects, lying ghostly. “It was like everyone just walked out and never came back, which is exactly what happened.”

As a journalist, Mellon has covered the transition from that world to the one Pittsburgh has become — a “meds and eds” city built around education, tech and medicine and the various places they intersect — and has become familiar with what the loss of that kind of work did to the generation of workers who watched it go.

“A lot of these guys took so much of who they were from the physical work they did, and from being the provider for a family,” he says. “If they got new jobs, they didn’t make nearly as much money. Their wives would often have to get jobs to support the family, and for these older, traditional guys, that was a big blow to their idea of themselves as a man.”

Pittsburgh generally weathered this shift better than many similar cities and towns, but Mellon says that years after most of the closures happened, trauma lingered. “We saw a lot of suicides.”

In 1992, The Pittsburgh Press closed down, and Mellon — newly intimate with what a loss of work can do to you — spent time as a freelancer following the wave of deindustrialisation as it rolled back over autoworkers in Flint, Michigan; coal miners in Matewan, West Virginia; textile workers in Lewiston, Maine.

“Hell with the lid taken off,” visiting writer James Parton called Pittsburgh in 1866. The city’s position in the crook of three converging rivers allowed steamboats to reach the coal reserves in the nearby hills, and Pittsburgh quickly grew into one of the great industrial cities of the Gilded Age. The Heinz family has its origins here, Westinghouse too. But it is steel that defines Pittsburgh’s industrial history.

By the early twentieth century, it was producing roughly 60% of the nation’s steel. The “smoke, smoke, smoke”, which inspired Parton’s view, would fog the Pittsburgh streets for well into the second half of the century. You can see it in photos from the era, looking like London during the blitz, whole suburbs engulfed in churning, bubbling cloud. Steel was the organising principle of life in this area for most of the century — the main characters in The Deer Hunter, that elegy to American decline, were steel workers from Clairton, about 25 miles south of here.

That way of being disappeared like most of its equivalents in the Anglophone world — it was dismantled, piece by piece, starting in the late ’70s. The union movement took a hit, as it did everywhere, its membership now a third of what it once was.

The role of unions has been an intriguing subplot in this election. Famously the Teamsters Union declined to endorse anyone, saying it had “found no definitive support among members for either party’s nominee”. But other unions have been vocal, particularly United Auto Workers president Shawn Fain, who spoke at the Democratic National Convention wearing a T-shirt that read “Trump is a Scab”.

Mellon acknowledges that his view may be coloured by having been in a long period of industrial action, but says he’s never seen union involvement like he has in Pittsburgh in recent months.

“Union membership has been falling in the US, like it has everywhere, but I think that still means something. Unions still know how to organise, how to knock on doors, how to get people out there.”

And as organisers hit every doorstep across the city, both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump are heading here for competing rallies on the last day before the election.

See if you can spot some subtle differences in approach over the weekend: Harris made a last-minute cameo on Saturday Night Live, while Trump may or may not have suggested that recent convert to never-Trumpism Liz Cheney ought to face a firing squad (for her love of war, if that helps).

Rumours have it that Harris may be joined at her Pittsburgh rally by Taylor Swift, while Trump — lord forgive me for how sincerely this made me laugh — pretended at a rally to fellate his microphone.

Trump is many things, and one is a natural shock comic. I thought of that line of Bukowski’s where men, desperately fatigued by their meaningless labours, say “mad, brilliant things … Hell boils with laughter”.

As I finished my applications for media accreditation for Monday’s campaign events, I saw footage online of Trump in Lititz, 260 miles east towards Philadelphia. He gestured to his bulletproof glass:

“I have this piece of glass here,” he said. “But all we really have over here is the fake news, right? And to get me, somebody would have to shoot through the fake news.”

“And I don’t mind that so much,” Trump said. “I don’t mind. I don’t mind.”

The crowd laughed and roared.

Stay tuned as Crikey files from the Harris rally in Pittsburgh, her final appearance of the campaign.

Stay tuned for the next instalment of This American Carnage — Crikey files from the Harris rally in Pittsburgh, her final appearance of the campaign.