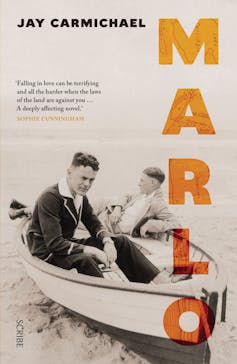

Marlo, a gay love story set in 1950s conservative Australia, draws on library and archival research. We know this because at the end of his book, author Jay Carmichael – a gay man himself – cites the work of Denis Altman and myself (in my role as a gay historian), among others. The novel is illustrated with photographs from collections in the State Library of Victoria and the Australian Queer Archives.

Review: Marlo – Jay Carmichael (Scribe)

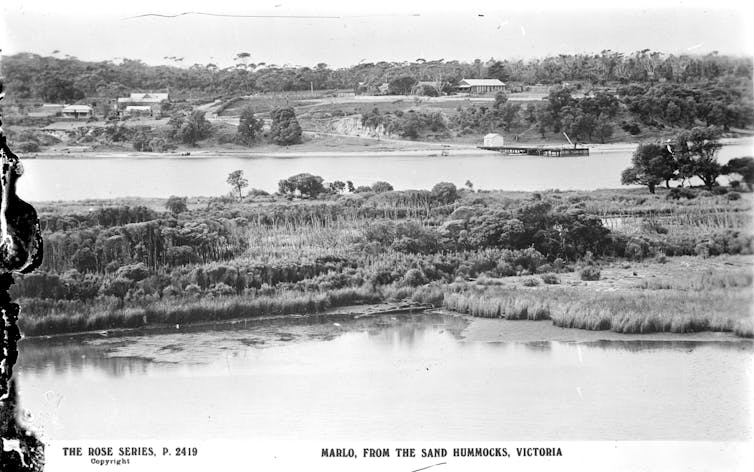

Marlo concerns central character Christopher’s sexual coming-of-age, after moving to Melbourne as a young adult from the small country town of Marlo in East Gippsland. The novel explores how same-sex-attracted men lived their lives during the repressive period following the end of the second world war.

Christopher moves to 1950s Melbourne, where he finds a job as a mechanic and shares a house with a friend from Marlo, Kings, and his girlfriend. During a picnic in the Botanic Gardens, Christopher bumps into another suit-wearing young man, Morgan, who later in the novel we discover is an Aboriginal Australian, living in white society with a Certificate of Exemption from the Board for the Protection of Aborigines (New South Wales).

Christopher and Morgan struggle with what appears to be Christopher’s self-loathing and yearning for acceptance.

Camp men in 1950s Melbourne

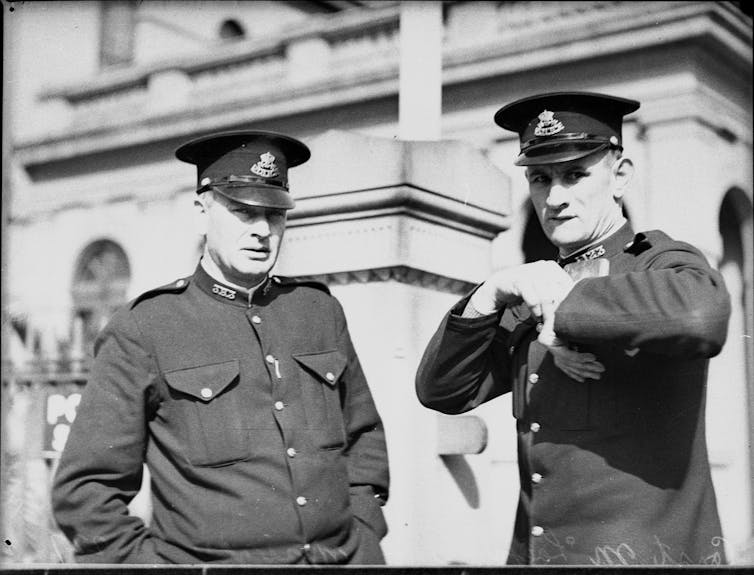

Same-sex-attracted men were known as “camp” before gay liberation popularised the term “gay” for homosexual men. Their lives were made more difficult by the association between sexual nonconformity and the political threat from Communism.

Marlo is at its most convincing when dealing with the social life that was available to camp men in 1950s Melbourne, and the discretion men like Christopher needed in order to pass, until they felt secure about who they were talking to and socialising with.

Women in tailored suits. A singer onstage […] Men in ball gowns. Each different. In this café, together, they made a whole. Distinct and complete. They were the same in that they were outcast, outlawed, underground.

Christopher’s relationships with his sister Iris and his boyfriend Morgan, and the tensions they created for him, are intriguing:

As we danced, I could have told Iris that the connection I felt with Morgan was similar to the connection I felt with her […] But it was her wedding night; all this could wait for a better time. Then again, I couldn’t be sure there ever would be a better time".

Before Christopher met Morgan, Iris had been his emotional anchor, but she wasn’t privy to knowledge of his sexuality. Despite Morgan’s reservations, Christopher insists that he join him at Iris’s wedding.

Morgan goes for a jog when they arrive at Christopher’s family home, is shunned by Iris, and wisely refuses to attend the wedding celebrations. The novel sets up but does not fully deal with Christopher replacing his dependence on Iris with his love for Morgan.

Repressive society, repressed self

In places, Jay Carmichael’s prose is inspired and elegiac:

And in the morning, before the world was clear-eyed, we would go, quiet, to our days.

On one occasion, as the physical relationship develops between Christopher and Morgan, he investigates Morgan’s body for any evidence of self harm:

In the shower, I checked his arms for self-inflicted scars or marks […] He did not have a blemish, but I determined he carried them within.

But he shows less interest in Morgan’s arms, thighs, genitals – or anything approaching the erotic.

It seems somewhat odd also that as a man in his 20s, ruminating over his budding physical relationship with Morgan, Christopher continued to use the term “things” to describe his genitals. (Which readers were first introduced to when as a child, his friend, Kings, showed Christopher his “things”.)

The connection the author might have intended here – between a repressive external society and an internalised, repressed view of the self – was not something my research revealed in men who were born in the 1920s and ‘30s and were sexually active in 1950s Australia. Many admitted to cautiously conducting their social/sexual relationships to avoid attracting the attention of homophobes, others to positively welcoming the police raiding their parties – for the “mystique” it brought them.

À lire aussi : Faggots, punks, and prostitutes: the evolving language of gay men

Occasional jarring notes occurred when other present-day features intruded in this novel set in the 1950s – when, for example, picnickers in the Botanic Gardens had “bubbly” with lunch. (I am not a cultural historian but suspect that, if drunk in Melbourne in the 1950s, champagne was the preserve of a small elite.) The scene seems more like a present-day invention than a reflection of the past.

And, when Christopher had a “duvet” over his legs and later opened a bottle of “merlot” after finishing work in a mechanics’ garage, my credulity as a reader was tested.

While these factual anomalies might seem slight, they may cause readers to wonder about the author’s other historical representations.

In my view, a weakness of the novel is its focus on what I suspect are the author and his peers’ current concerns (such as self-harm). Forcing these and other improbable material features on the past suggests an insufficiently strong understanding of history.

There is an important difference between using our current interests to investigate the past, which Carmichael suggests he is doing, but did not do well in my view (the author’s note explaining his sources runs to eight pages) and imposing our present-day concerns on the past. I suspect he has done the latter.

Some writers of historical novels are known to spend months verifying everyday facts from the past: dress, modes of social interaction, food, drink and diet (for instance).

Examples of those who have excelled in this field include Mary Renault (The Persian Boy and other books in her Alexander the Great trilogy), Marguerite Yourcenar, first woman elected to the French Academy (Memoirs of Hadrian, Coup de Grâce), and more recently, Hilary Mantel (Wolf Hall).

When done well, the historical novel shows how good writing and a strong grasp of history can enhance a richer understanding of the past.

Peter Robinson ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.