In 1981, Issei Sagawa shot a Dutch woman dead in Paris and, over the following two days, ate parts of her body. He managed to not only escape justice but also profit from the killing.

The past 20 years, though, have not been kind to Sagawa. He has gone from a decade of relative fame in Japan as an author, magazine columnist, novelist, restaurant reviewer, television commentator and even porn star to penury, obscurity and failing health.

He will soon be thrust into the headlines in his homeland once more by a film that retells his grisly story and seeks to explain his mental state.

Caniba is a joint French-US production that will be released in Japan on July 12 and has already been screened to what can only be described as mixed responses. The review at the exquisiteterror.com website described the film as “intimately shot” and a “confidential intoxicatingly claustrophobic portrait” of Sagawa. Asian Movie Pulse said it was “intense” and “a unique experience, a truly original movie”.

The reaction at a number of film festivals has been less enthusiastic: many people attending the screening at the Venice Film in 2017 walked out. The reaction was similar at the Toronto Film Festival the same year.

Soon it will be the turn of Japanese audiences to register their verdicts.

While studying literature at the Sorbonne in Paris, Sagawa convinced a Dutch student named Renee Hartvelt to join him at his flat for a meal. He shot her in the head, sexually abused her corpse and ate part of her body. He was caught trying to dispose of what was left of the corpse in the ponds of the Bois de Boulogne. Police found parts of Hartvelt on plates in Sagawa’s fridge.

Before he could be tried, a court found Sagawa mentally unfit to stand trial and he was committed to an asylum. His wealthy parents soon petitioned the authorities in Paris to release their son on the grounds he was too far away from home and the French were apparently only too glad to put him on a flight back to Japan.

In Japan, however, Sagawa’s parents found a compliant psychologist who declared their son was not insane and therefore no longer needed to be detained. He was released and re-entered Japanese society, embracing his new-found celebrity status.

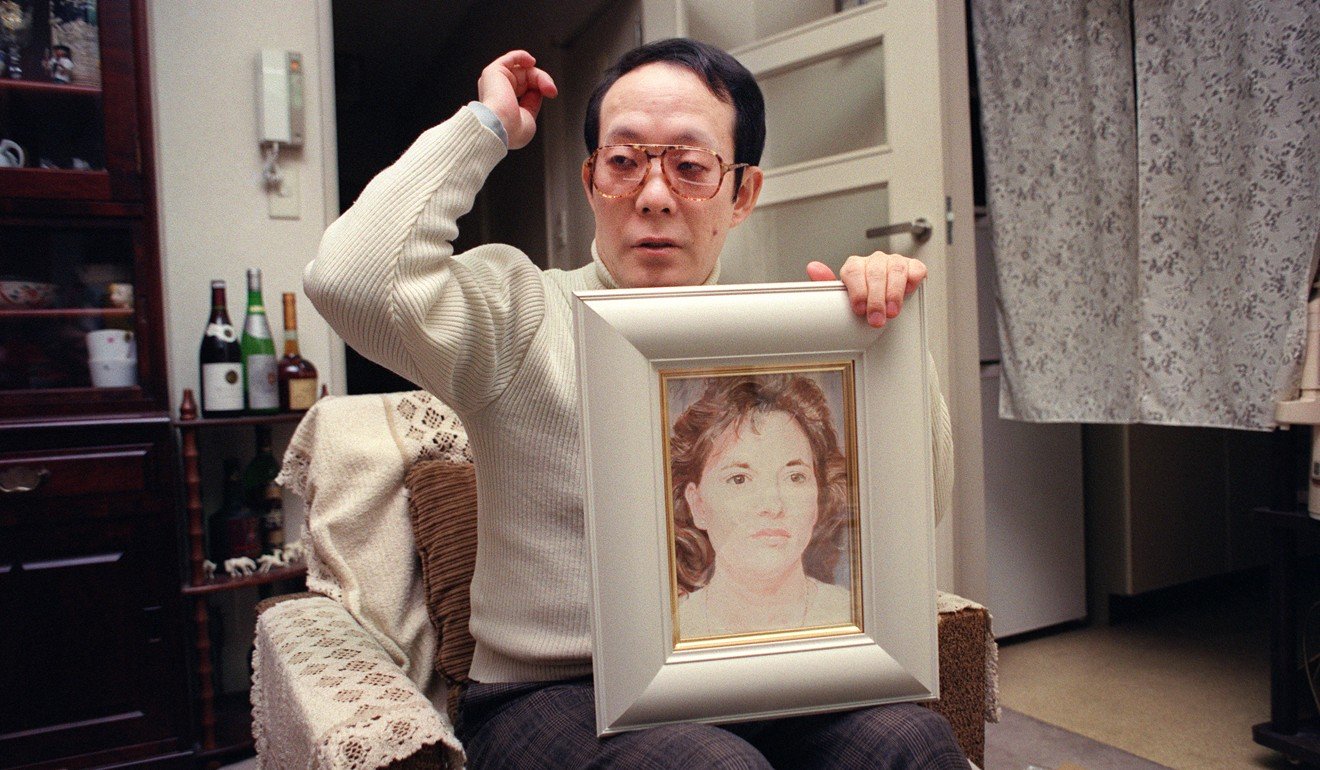

Sagawa was invited to pen columns for popular magazines. He wrote his memoirs, In the Fog, and a couple of novels. He appeared on television chat shows and even a cooking show where he made a meal of sampling meat dishes. In his porn movie performance, he was invited to chew on the buttocks of his female co-star.

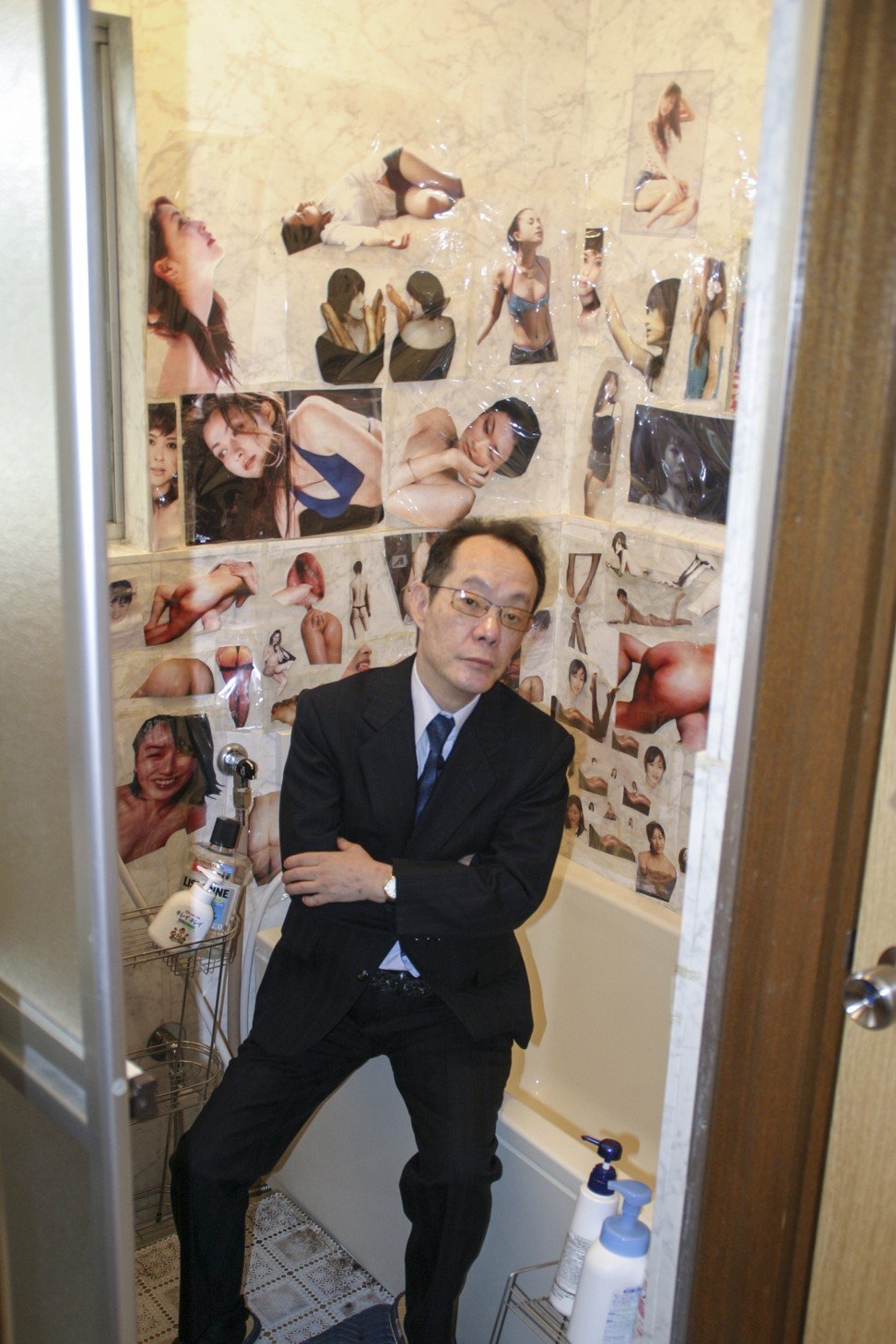

His fame has since waned – he reportedly survives on his inheritance and fees for interviews. Sagawa’s younger brother, Jun, has been taking care of him since he suffered a cerebral haemorrhage in November 2013. More recently, Jun told the Shukan Shincho news magazine his brother has undergone a gastrostomy and can no longer eat.

His story should have meant it was impossible to employ him, even though he was never convicted – Makoto Watanabe, Hokkaido Bunkyo University

Sagawa is fed through a tube directly into his stomach, and his condition is worsened by chronic diabetes. His health insurance means he is regularly forced to change hospitals in Kanagawa Prefecture, south of Tokyo.

Jun told the magazine his brother still watches dramas with his favourite actresses, Erika Toda and Satomi Ishihara. He also confirmed his brother still gets the urge to “eat a woman”, despite his ill-health and turning 70 earlier this year.

“It has been such a long time since most people heard his name that I think everyone has pretty much forgotten him,” said Makoto Watanabe, an associate professor of media and communications at Hokkaido Bunkyo University.

“Personally, I don’t remember the case at all and I don’t recall seeing him on television, so I can only imagine that this movie is meant to attract attention because it is so shocking. It’s basically a documentary horror show of a subject that is taboo.”

Watanabe admitted to being “at a loss” when pressed to explain how Japanese media could have deemed it appropriate to hire a man who freely admitted to killing and consuming a woman.

“I cannot understand why they would use him for entertainment,” he said. “His story should have meant it was impossible to employ him, even though he was never convicted, and it is wrong that he made money from his notoriety.”

Watanabe predicted Japanese media would today behave differently but suggested Sagawa’s celebrity was an unsettling reflection of Japanese society at the time.

“Sagawa was never forced to take responsibility for his actions, but because he was never found guilty then in the eyes of many Japanese he was not responsible,” Watanabe said. “The sense was that it could be overlooked and things could go on smoothly. Nobody wanted to raise a voice against a decision to hire him.”

Mieko Nakabayashi, a former politician and now a professor in the school of social sciences at Tokyo’s Waseda University, echoed that sense of bewilderment.

“It is hard to understand how the media back then ignored the facts of the case and paid him for columns and television appearances,” she said. “Nowadays we might see a celebrity making a comeback after being punished for something like drugs but killing someone is a different matter altogether.”

One explanation for the willingness to give Sagawa publicity is the rivalry that existed between TV stations and publishing houses as they tried to shock viewers at a time when the Japanese economic bubble was at its peak, money was no obstacle and ratings were all-important, Nakabayashi said. The producers and publishers may have justified their actions by pointing out that Sagawa had never been convicted.

“He may also have had personal connections in that world that helped him to get appearances,” she said. “However he did it, I’m sure it could not happen like that now.”

Yet it appears at least one company is happy to try to make money out of Sagawa again.

Masaki Osawa, deputy editor of Tocana, the company distributing the film, said 11 cinemas have agreed to screen it, with runs of between three and five weeks.

“We wanted to bring the film to Japan because all other Japanese companies had refused to distribute Caniba,” he said. “Secondly, we believe that more Japanese people should know about the murder that Sagawa committed – and especially young people, who barely know about this horrible case.

“Yes, Caniba contains some sensational scenes, but this film is not only focusing on fear or the horror of cannibalism, but also the dark deeds and desires of humanity.”