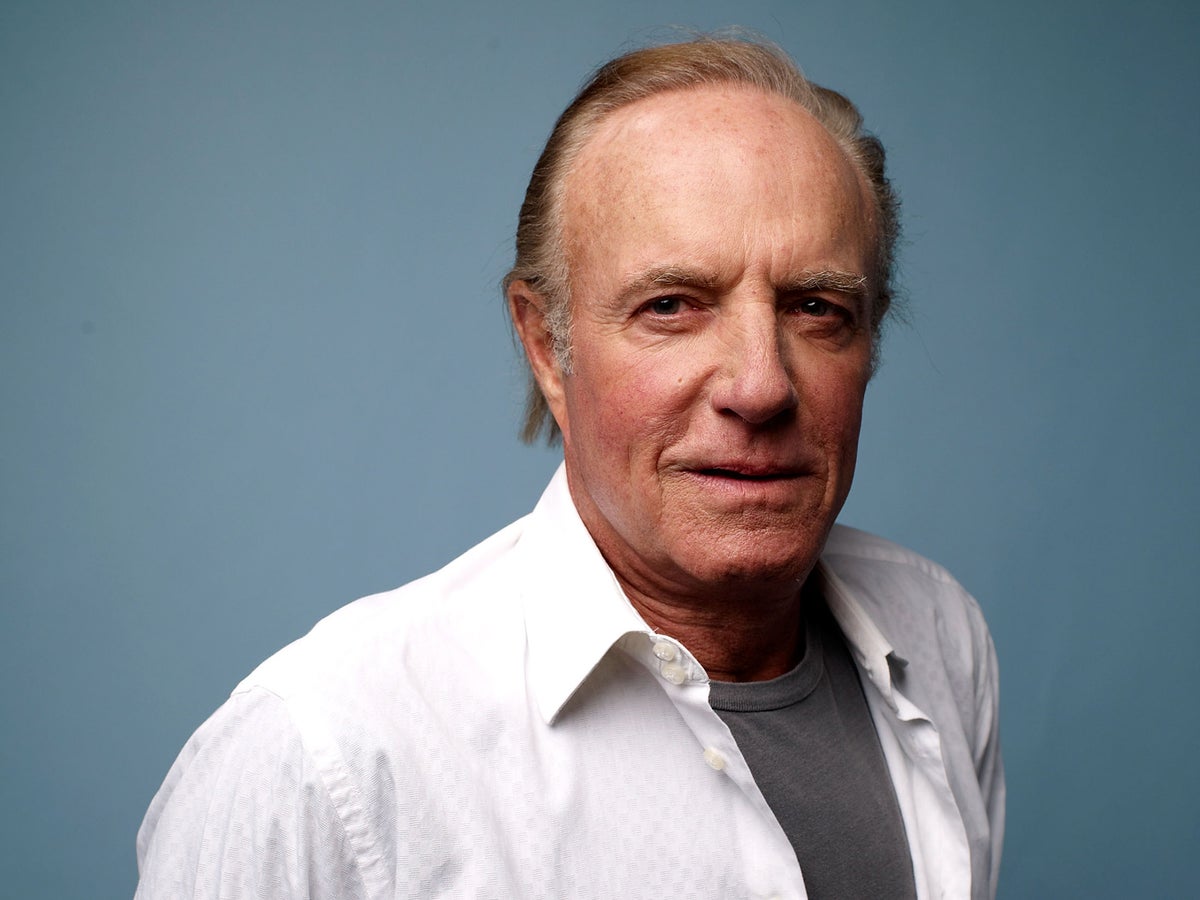

James Caan, a Hollywood leading man of the 1970s who memorably displayed his tough-guy screen presence as the trigger-happy Mafioso Sonny Corleone in The Godfather – but who also proved, beyond his macho exterior, a versatile performer of wry expressiveness and unexpected vulnerability – has died aged 82.

The son of a butcher who had fled Nazi Germany, Caan grew up in the 1940s and Fifties on the knockabout streets of New York’s outer boroughs. A wiry boy, he was dubbed “Killer Caan” for his use of his fists in self-defence, and he prided himself on never losing his street-wise edge or raspy Queens accent. He remained, he said, just a “punk from Sunnyside”, even as his enigmatic smile and aura of danger propelled a Hollywood career lasting six decades and spanning more than 130 credits.

He maintained his strut and bravado off-screen, earning a black belt in karate and pursuing hobbies such as powerboat racing and roping steers. “I think I can safely say,” he observed, “I was the only Jewish cowboy from New York on the professional rodeo cowboy circuit.” Admittedly headstrong and at times self-destructive, he endured the tumult of cocaine addiction and four divorces.

Film critic Roger Ebert admiringly called him “the most wound-up guy in the movies”, a description Caan did not dispute. Shortly after the box-office success of Misery (1990), in which Caan played a novelist held captive by a hammer-wielding deranged fan, Caan joked that director Rob Reiner had indulged in a sadistic game by forcing him – “the most hyper guy in Hollywood” – to perform the role tied to a bed over 15 weeks of filming.

Caan had gone into acting on an impulse, desperate to avoid “humping sides of meat from trucks to restaurants” with his father in the bitter chill of dawn. He had a talent for making people laugh, a skill he honed one summer as a Catskills resort social director, and bluffed his way into a prestigious theatre training programme in Manhattan, the Neighborhood Playhouse.

With his brooding good looks and coiled unpredictability, Caan won a long string of guest parts on TV before entering movies. But he showed, when given the chance, understated intelligence and sensitivity as a performer.

Reviewers praised him as a brain-damaged ex-jock in The Rain People (1969), directed by Francis Ford Coppola but hardly seen because studio executives lost faith in its commercial appeal. His breakout role was the terminally ill Chicago Bears running back Brian Piccolo in the TV film Brian’s Song (1971).

The ABC movie, which touched on interracial friendship, attracted 55 million viewers and earned Caan an Emmy nomination as best actor. The next year, Coppola tapped him to play Sonny Corleone, the eldest son of the mafia kingpin in The Godfather.

In a cast that included Marlon Brando as his ageing father, Vito, and Al Pacino as his sombre younger brother Michael, Caan more than held his own as the coarsely sexy and hot-tempered Sonny. To get into character, Caan said he found unlikely inspiration in comedian Don Rickles and his unnerving style of “busting everybody’s chops” in vicious takedowns.

Advising Michael on how to kill a rival mobster and a corrupt police captain, he declares that “you gotta get up close, like this – and bada bing! You blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit”.

The phrase “bada bing” was improvised by Caan and “became a mantra for mobsters and aspiring mobsters”, Vanity Fair reported in 2009, and served as the name of Tony Soprano’s strip club on the HBO TV show The Sopranos.

Sonny gets his comeuppance when he is bloodied in a battlefield’s worth of machine-gun fire while trapped in his car at a tollbooth. In a scene that took three days to film, Caan wore nearly 150 tiny explosive charges called squibs. “When they went off, it felt like I was being punched all over,” he told The Observer. “If my hand had got in front of one, it would have blown a hole clean through.

“I wouldn’t have done it,” he added, “if there hadn’t been so many girls around the set to impress.”

The Godfather was a commercial juggernaut, won Academy Awards including best picture, helped reinvigorate the gangster genre and was ranked behind only Citizen Kane on the American Film Institute’s 2007 list of greatest films of all time. Caan, who was nominated for a best supporting actor trophy, was inundated for decades with exact-change and E-ZPass jokes.

After The Godfather, Caan said he was rarely given a script that did not feature a pile of corpses in the first 10 minutes. Determined to avoid typecasting, he ventured into offbeat comedy with Slither (1973); played a sailor who winds up looking after the interracial son of a prostitute in Cinderella Liberty (1973); and showed off a pleasant singing voice as theatrical showman Billy Rose in Funny Lady (1975), which starred Barbra Streisand as entertainer Fanny Brice.

He was an athlete in a nightmarish game of state-sponsored murder in Rollerball (1975), a heroic Army sergeant in the all-star Second World War drama A Bridge Too Far (1977) and a master safecracker in Thief (1981). For the last, which he regarded as his finest performance, he learned proper techniques from former crooks who had been hired as technical advisers.

In his quest for variety, he ended up with several misfires and mediocrities, including Freebie and the Bean (1974), which Caan later dismissed as “The Odd Couple in a squad car”. He turned down leading parts in era-defining dramas such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Kramer vs Kramer (which he dismissed with an epithet as “middle-class bourgeois” bull) and Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.

“When Francis called me up about Apocalypse Now, all I heard him say was ‘16 weeks in the Philippine jungle’,” Caan told The Washington Post, explaining his rejection.

In the same interview, he added that Brando was incredulous when Caan refused the title role of Superman (1978) despite being offered – like Brando, who played Jor-El – millions of dollars for what was literally a cartoonish role. “Yeah, Marlon,” he replied, “but you don’t have to wear the suit.” (The film launched a hit franchise, with Christopher Reeve in the title role.)

As his career teetered, Caan increasingly developed a reputation for wayward personal and professional behaviour. In interviews, he seemed unable to control his badmouthing of movies by powerful directors, in particular the Hollywood infatuation with special effects over character-driven plot.

He starred in and directed a critically lauded, low-budget drama, Hide in Plain Sight (1980), based on the true story of a man’s battle to find his children when his ex-wife and her mob-informant husband go into the witness-protection programme. But he said the studio buried it. “There were no sharks in it, so these two idiots over at MGM didn’t know what to do with it,” he told The Independent.

Meanwhile, he pursued a decadent lifestyle as a habitue of the Playboy Mansion. He spiralled into cocaine addiction after the death of his younger sister and closest confidant Barbara, from leukaemia in 1981. Around that time, he lost his life savings – and his home – after it was discovered that he owed hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes. He blamed incompetent business managers but also himself for being too addled by drugs at the time to notice.

Caan entered drug rehabilitation at least twice in the 1980s and 1990s, and he continued to be pulled into headlines during those years, once for allegedly slapping and choking a girlfriend and once for brandishing a gun during an argument over a parking space. He also publicly acknowledged his friendship with reputed mobsters.

He was all but unemployable when Coppola fought for him to star as an Army sergeant in the Vietnam-era military drama Gardens of Stone (1987). Critics lauded his subdued and affecting performance as a loner who loves the Army but hates the war. However the film faded quickly from attention.

Greyer and weathered, but still with a menacing charisma, Caan began his return to prominence with a run of intimidating character roles. Channelling the spirit of Sonny Corleone, he appeared in the crime comedies Honeymoon in Vegas (1992), Bottle Rocket (1996) and Mickey Blue Eyes (1999).

James Edmund Caan was born in the Bronx on 26 March 1940. After being kicked out of several public schools for disruptive behaviour, he managed at 16 to graduate from the Rhodes School, a now-defunct Manhattan prep academy, half-joking that teachers accelerated him just to be done with him.

He entered Michigan State University with the hope of playing on its vaunted football team, but he said he wound up as “tackling dummy”. At Hofstra College (now university), he dropped out after getting into a fistfight with an ROTC superior. He was a lifeguard and a bouncer, among other odd jobs, before entering the Neighborhood Playhouse in Manhattan on a whim.

After brief theatre experience as a spear carrier, he moved to California. In one of his earliest screen parts, he was a sadistic hood who torments Olivia de Havilland while she is trapped in her home elevator in Lady in a Cage (1964).

Caan’s marriages to dancer Dee Jay Mattis, Sheila Ryan (a Playboy model and one-time girlfriend of Elvis Presley), Ingrid Hajek and costume designer Linda Stokes ended in divorce. Survivors include five children.

In a career and private life marked by vicissitudes, he was grateful for his association with a popular hit (Misery) and a cinematic landmark (The Godfather).

“Look, you only pray when you start in this business that you get to the point where people recognise you,” he told Cigar Aficionado magazine. “I’ve got a lot of people who are, like, ‘Hey, your ankle OK?’ from Misery. ... Or they’ll say, ‘Hey, don't go through that toll booth again’ or ‘Have the right change.’”

“It means that they remember the picture,” he added. “There’s nothing not to like about it. The only thing that I get a little upset about is when I’m in a restaurant and people ... beckon me with their finger. I get a little sideways. I go, ‘No, you come here! What, am I a taxi or something?’”

On the other hand, he said, “I hope they never stop.”

James Caan, actor, born 26 March 1940, died 6 July 2022

© The Washington Post