*

January 23, 2020

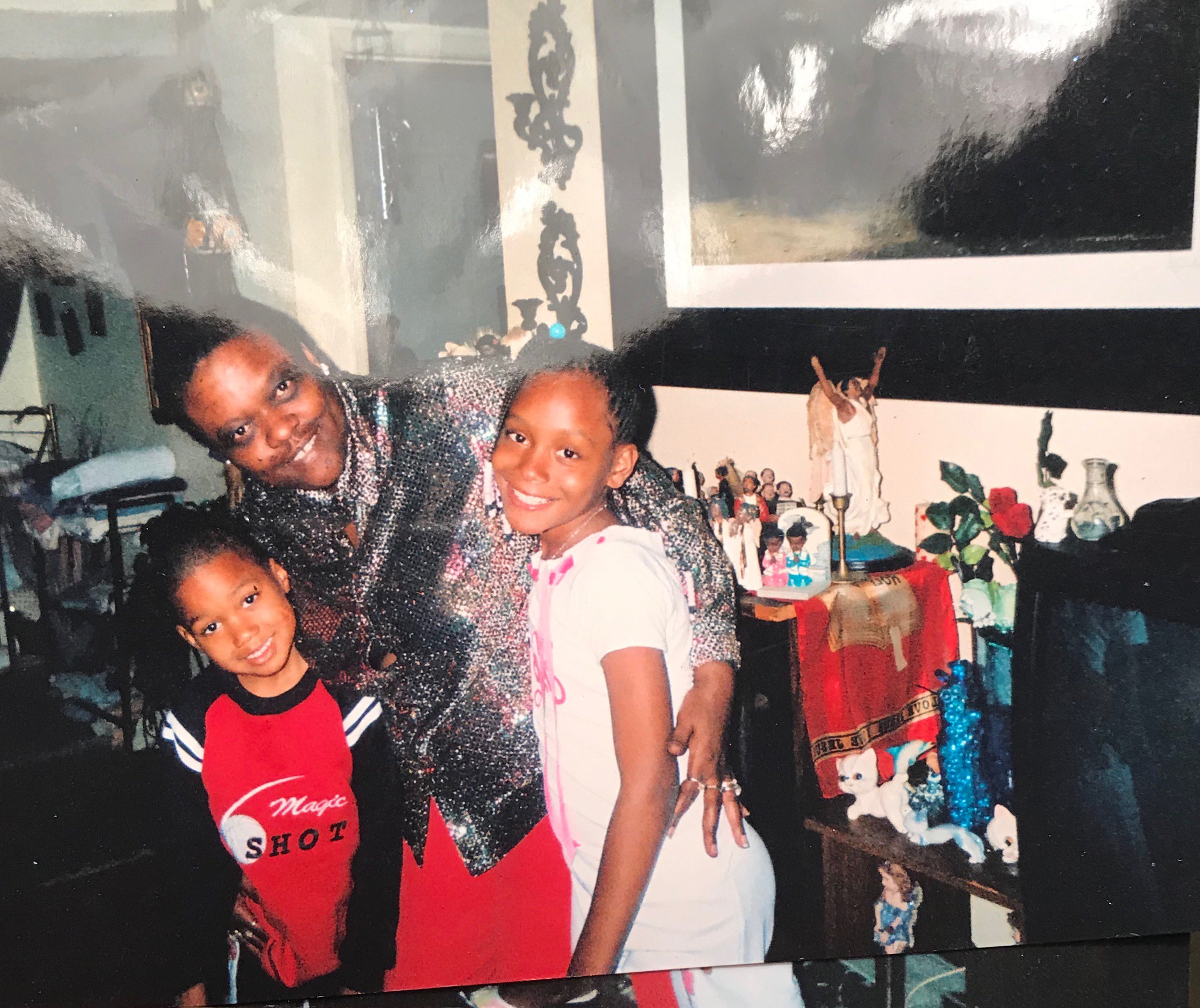

Stephen Wayne Cole’s family expected him to visit them in Houston this Christmas, just like he did every year. Joana Garrett, his little sister, says making menudo together had become a holiday ritual she looked forward to. But December 25 came and went without a word from Cole. Garrett spent the week wondering where her brother was until, on December 26, her sister called with devastating news: Cole, 61, had died 200 miles away in a San Antonio jail cell. When Garrett picked up the phone, all she could hear was her sister wailing. “It was just screaming and hollering, like something or somebody was killing her,” she says. “I wouldn’t wish that kind of call on anybody.”

Although the medical examiner has yet to report a final cause of death for Cole, the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office blamed it on “an underlying medical condition and chronic narcotics use.” Medical records obtained by Cole’s family show that staff at the Bexar County jail didn’t order his prescribed heart and blood pressure medications—which his family says he took religiously to avoid feeling sick—until December 25, three days after he’d been detained for a criminal trespass charge. Records indicate that Cole missed his first appearance before a judge because he soiled himself on the way to court. According to medical records, treatment was “delayed due to slow and inadequate notification by detention staff” after Cole collapsed in his cell on December 26.

Cole’s death in lockup is the latest in a string of tragedies at the Bexar County jail to raise serious questions about the medical care that vulnerable and sick people receive behind bars. Court records from lawsuits filed by the families of those who have died paint a picture of neglect and dubious medical care from University Health System, the jail’s longtime medical provider.

Garrett tears up when she thinks of her brother spending Christmas in a jail cell rather than in her kitchen. “To know that he was sick and hurting in there, it just makes me that much more upset,” she says. “He didn’t have to die in there.”

*

Thanks to a lawsuit filed by a Texas inmate in 1973, incarcerated people are the only population in America with a constitutional right to health care. J.W. Gamble had repeatedly complained of severe back pain after a 600-pound bale of cotton fell on him while he unloaded a truck at the Huntsville Unit’s prison textile mill. Prison staff only gave him pain relievers, then threw him in solitary confinement when Gamble said he couldn’t work (he was never given an X-ray). When Gamble’s lawsuit reached the Supreme Court, Justice Thurgood Marshall—writing for eight of the nine justices who sided with the prisoner—said that such “deliberate indifference to serious medical needs of prisoners” violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Under the legal precedent that followed, everyone in government custody—from pretrial detainees who are legally innocent to convicted prisoners serving out long sentences—is entitled to adequate treatment for their ailments. But allegations of medical neglect are common in lockups across Texas and the rest of the country. Problems are often more pronounced in jails because people just booked into custody are frequently in crisis or have had treatments disrupted.

People suing for shoddy medical care behind bars must demonstrate that prison or jail staff were aware of and yet completely disregarded serious medical risks to an inmate. Civil rights lawyers often zero in on the failure of jail staff to order standard tests and treatments after accidents or medical complications in lockup, as was the case with Robert Mosley, 54, who died at the Bexar County jail on July 26, 2015.

Mosley, who was addicted to alcohol, had turned himself in four days earlier to resolve a 12-year-old DWI charge. He began exhibiting withdrawal symptoms soon after booking, according to court records. While it’s still unclear whether Mosley fell or was pushed inside his cell (officials first called his death a homicide but then relabeled it an accident), Mosley told guards and nurses that he thought he’d broken a hip three days after he was booked into the jail. Nurses working for University Health System saw Mosley—who couldn’t walk on his own and complained of persistent, searing pain—but sent him back to his cell without requesting an X-ray. According to court records, one of the nurses who discharged Mosley back to his cell noted that the “inmate stood on his own,” even though a guard later testified in a deposition that Mosley could only stand with guards holding him up by each arm.

Mosley spent the night lying on a mat on the floor because he couldn’t crawl into his bunk. Guards filed a request for a psychiatric evaluation after observing that Mosley was confused, unable to follow directions, and hallucinating. According to jail records cited in court, Mosley couldn’t stand up and dragged himself around the cell, as if “mopping the floor with himself.” The following morning, a guard found Mosley unresponsive and in a puddle of his own urine. An autopsy report later showed a fracture to the socket area of Mosley’s hip joint, which caused massive internal bleeding that eventually led to multiple organ failure and death.

A lawsuit filed by the civil rights clinic at the University of Texas Law School on behalf of Mosley’s family argues that jail and UHS staff failed to care for his obvious and serious medical needs. According to court records, UHS officials have acknowledged failures in Mosley’s treatment at the jail, but no staffers were ever reprimanded. A trial in federal court is currently scheduled for March.

The death of a loved one in law enforcement custody can be a particularly a bewildering loss because agencies don’t often make it easy for families to piece together what happened behind bars, says Ranjana Natarajan, who directs the law school’s civil rights clinic and has helped represent Mosley’s family in court. State law requires agencies to track all deaths in custody and document them with the Texas Attorney General’s Office, but those sparse reports often raise more questions than they answer. Since the passage of the 2017 Sandra Bland Act, an outside agency must investigate all deaths in custody, but findings are rarely shared with grieving families, let alone presented to the public.

“It’s an added difficulty for families because they don’t get a sense of closure, because trying and struggling to find out what actually happened can be a heart-wrenching process for them,” Natarajan told the Observer. “When a person dies in custody, the jail shouldn’t just be required to conduct a thorough investigation, but also to come up with conclusions and make them public so that everyone knows what steps are being taken to increase the safety of people in that facility.”

*

Even as other jails and state prison systems began outsourcing treatment to scandal-plagued private prison contractors, Bexar County’s public hospital system has remained the medical provider for jail inmates for the past 25 years. But several deaths at the county lockup over the past year have cast doubt on the quality of that care.

Janice Dotson-Stephens, 61, who had a long and documented history of mental illness, wasted away in Bexar County custody after being arrested for criminal trespassing during a psychiatric crisis. Court records show that Dotson-Stephens, who died at the jail on December 14, 2018, lost nearly half her body weight during her 150 days in lockup, despite being seen hundreds of times by dozens of different UHS employees or contractors for mental health evaluations, observations, or other medical recommendations.

Jack Ule, 63, who also had a long history of debilitating mental illness, was homeless and struggling to find his footing after the death of his mother when police arrested him at the local public hospital last April. Ule, who died at the jail on April 18, sought care numerous times at University Hospital, the public hospital operated by UHS, before facility staff had him arrested for “loitering” in the waiting area for too long. According to a lawsuit Ule’s family filed against jail and UHS officials last month, Ule’s medical condition grew worse in lockup, but jail staff dismissed his complaints as “behavioral” problems that they attributed to his mental illness.

Bexar County officials promised change following the deaths of Dotson-Stephens and Ule, with DA Joe Gonzalez directing prosecutors to drop criminal trespass cases in certain circumstances. While Bexar County Sheriff Javier Salazar says he’s now investigating potential lapses in inmate care at the jail, it’s not yet clear what that probe might produce or how far along it is. A letter Salazar sent UHS officials last September shows he considered tapping a private prison contractor with a history of tragic failures to conduct an overview of the jail’s medical processes and facilities. Salazar, who faces a primary election in March, told the Observer he’s since ditched the idea of a private company and decided to approach a community and correctional health care nonprofit instead.

“Currently, we’re looking at overall practices, but we’re looking at it as a law enforcement agency, so I still need someone with a health care background to come in and tell us best practices,” Salazar says. “We’ve got some investigations ongoing, knowing full well that maybe we find nothing, but maybe we’ll find some criminal negligence on the part of somebody.”

In a statement, Elizabeth Allen, public relations manager for UHS, said the hospital district hasn’t been approached by the sheriff’s office for any “purported investigation.” Allen didn’t answer questions about the cases cited in this story due to pending litigation but said in a statement, “University Health System believes it is important that it work hand in hand with the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office to ensure that inmates continue to receive quality health care.”

Leslie Sachanowicz, an attorney representing the families of both Dotson-Stephens and Ule, says the past year of deaths at the jail point not just to inadequate health care, but also to ingrained bias—against poor people, against people experiencing homelessness, against those with mental illness. Dotson-Stephens and Ule had documented histories of mental illness, and yet police sent them to jail rather than filing for emergency warrants to put them in treatment. Court records list both Ule and Cole as being homeless.

“This callous treatment, I want people to realize that it’s their tax dollars that are paying for that kind of care,” Sachanowicz told the Observer.

*

Last Friday, Joana Garrett traveled to San Antonio to help bury her brother. Stephen Wayne Cole, originally from Lubbock, had moved to the city about four years ago. He told Garrett he wanted a fresh start and thought San Antonio seemed like a nice, welcoming place.

Garrett thought her brother seemed depressed since the death of his father about a year ago. But the family didn’t know he was homeless, nor did they realize that he was in jail until it was already too late. “I would have paid to get him out,” Garrett says. “I was already going to buy him a bus ticket to come see me, but then I never heard from him.”

Cole was arrested on December 22 but remained in jail through Christmas because he couldn’t afford $400 bond. Ule was jailed for weeks because of a $300 bond he couldn’t pay. Dotson-Stephens spent months in the Bexar County jail even though a $30 bond payment could have secured her release.

After the memorial service and burial last week, Garrett went to the Bexar County jail to try to pick up her brother’s property. She says jail staff were brusque and unhelpful, even when she explained that her brother had just died at the facility. “I’m talking about rude all the way,” she says. “I wouldn’t wish for my worst enemies to go to that jail.”

Because she didn’t have the right paperwork, Garrett has to plan another 200-mile drive back to San Antonio to recover her brother’s belongings. She hates that she has to return. “I was so ready to get out of San Antonio after I left that jail the first time, I think I sped out the city limits,” she says. “To think of what my brother went through there, I don’t want to be anywhere near there.”

READ MORE:

-

A Solitary Condition: Texas has banished hundreds of prisoners to more than a decade of solitary confinement, an extreme form of a controversial punishment likened to torture. Many of these prisoners aren’t sure how—or, in some cases, if—they will ever get out.

-

Trump Harvests Support in America’s Farmlands: At a farm convention in Austin, the nation’s agriculture sector warmly welcomed a president who has hurt them in the past.

-

ICE Quietly Lowers (Already Low) Standards at Some Immigrant Detention Facilities: The changes—which affect 18 facilities in Texas—include giving guards more leeway to put migrants in solitary confinement, as well as no longer requiring outdoor recreation areas.